This article is part 2 in a two-part series.

As argued in my previous article, the improving credit rating enjoyed by the Philippines since achieving “investment grade” in 2013 was expected to boost financing for those firms and sectors that most needed it — yet small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and the agricultural sector were still largely marginalized from financing despite the benign credit environment of the past few years. Another expected boon from improved risk ratings is the increase in net FDI into the country. Unfortunately, emerging data on approved investment pledges show a dramatic decline in recent years, signaling potentially weak actualized FDI figures to come. The possible roots of this poor investment performance include several self-inflicted wounds, such as growing concerns over human rights violations and the uncertainty in the investor environment due to political noise on government contracts. And if not addressed soon, these problems will likely undermine any boon from improved credit ratings, if that hasn’t happened already.

Self-Inflicted Wounds Turning Away Investors?

The protracted discussions on the second package of the Duterte administration’s tax reforms, which includes a corporate income tax cut and a comprehensive rationalization of investment incentives, may have soured relations with many foreign investors that saw this as a possible reduction of tax breaks and other benefits. While well-intentioned, the prolonged uncertainty created by this reform — which still has not been passed into law — is likely keeping investors away. The government should either declare that they are abandoning tax reform, or get it passed soon with the compromises needed.

Furthermore, the government’s growing “anti-oligarch” and “anti-big-business” rhetoric may have raised uncertainty over the sanctity of contracts and the independence of regulatory institutions to review and renew franchises in the Philippines. This began in 2016, when President Rodrigo Duterte’s tirade against online gaming operator Roberto Ongpin caused the value of shares in Ongpin’s PhilWeb to drop from 24 Philippines pesos around February 2016 to around 6 pesos by September 2016. A majority share in PhilWeb was promptly acquired by Duterte ally Gregorio Araneta, at around one-fourth of the cost prior to Duterte’s Ongpin-targeted rants. Under Araneta’s ownership, PhilWeb’s license was subsequently renewed.

Manila Water Corporation (MWC) is a more recent case. A celebrated example of water privatization that produced dramatic improvements in access to water in parts of Metro Manila, Manila Water was recently blamed by Duterte and his allies for the Metro’s water woes in 2019, causing Manila Water stocks to plummet from a trading high of about 27 pesos in early 2019 to about 6 pesos by mid-December that same year. Investor uncertainties were fanned by the Duterte administration’s not-so-veiled threat to re-nationalize water services, as well as renege on the previous arrangement to extend Manila Water’s contract to 2037 (from an initial expiration date in May 2022).

Enrique Razon subsequently purchased a quarter of MWC shares in early February 2020, at 13 pesos per share. These shares cost Razon “only” 10.7 billion pesos ($210 million) — an investment easily worth twice that amount just a year before, prior to the pressure from Duterte. Razon also obtained control over the company, serving as a “political white knight.”

Once again, someone seen as a Duterte ally swooped in to acquire an ownership stake in a company after Duterte himself caused the fire-sale. Given growing speculation about favors given to political allies, and increasing concerns over the sanctity of contracts, it is likely that this uncertain environment is creating a “wait-and-see” attitude among many investors, notably as the Philippine elections are just around the corner in 2022.

Most recently, the president and his allies have applied growing pressure on the franchise renewal prospects of ABS-CBN, one of the largest media companies in the Philippines, which has at times been critical of the government and many politicians, including the Duterte administration (notably through its reporting on the anti-drug campaign). By signaling against renewal, Duterte and some of his allies have once again appeared to influence institutions with political motivations. No less than the administration’s chief economist, Secretary Ernesto Pernia, has noted that nonrenewal of ABS-CBN’s franchise could reinforce investor uncertainty and prove inimical to economic diversity and competition.

Riding the political business cycle has been the bane of Philippine investors since the Marcos regime. Every six years, investors reconsider whether the Philippines is still on the right developmental track. At any time, new players might enter different economic sectors, but in the words of a business leader who will remain unnamed: “They are interested to eat a larger piece of the economic pie, but don’t bother to grow it.” This is classic rent-seeking, plain and simple.

Rule of Law Includes Upholding Human Rights

Making the investment climate even more challenging, allegations of human rights violations in the Philippines, particularly as regards the still-popular anti-drug campaign of the Duterte administration, exposes an old vulnerability — that of impunity and chronic human rights violations — that well preceded the Duterte administration. Yet today, there appears to be global awareness and both domestic and international attention on this issue in the Philippines. The United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights as well as traditional economic (and in some cases also security) partners such as the United States and the European Union have also voiced their concerns.

Recent research finds evidence that countries that are cited for human rights violations actually face dramatic reductions in FDI inflows — up to a 49 percent reduction according to one simulation involving over 165 industrial and developing countries studied. Few investors in today’s highly competitive international investment landscape would like to deal with an international pariah — and that’s what a reputation of impunity and chronic human rights violations could eventually foment. In the face of this empirical evidence, it is surprising that so few credit rating analysts even discuss deep governance issues related to human rights.

Competitiveness and EODB on the Decline, Corruption on the Rise?

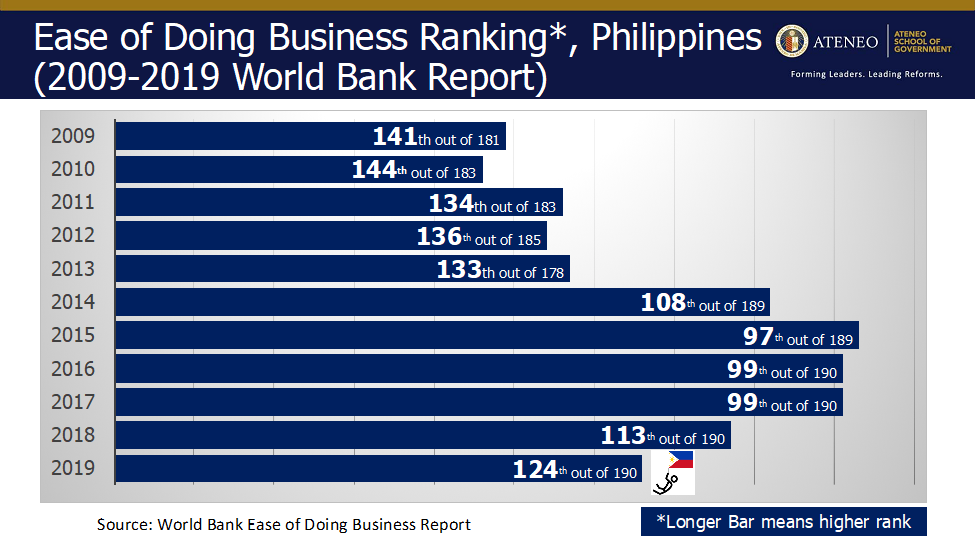

Beyond self-inflicted wounds, slow progress in other key reform areas could also hold investors back. Even as small and medium-sized firms account for a small share of total loans to Philippine enterprises, as noted earlier, these SMEs face even bigger challenges — challenges that make access to finance rather moot. These include the ease of doing business (EODB), which they often report in surveys as one of their chief constraints to expansion. EODB indicators for the country declined in both 2018 and 2019 as the Philippines slipped in rank, from being in the top 99 countries in 2016 and 2017 to 113th in 2018 and 124th in 2019 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Philippines slipped in EODB rankings, from being in the top 99 countries in 2016 and 2017 to 113th in 2018 and 124th in 2019.

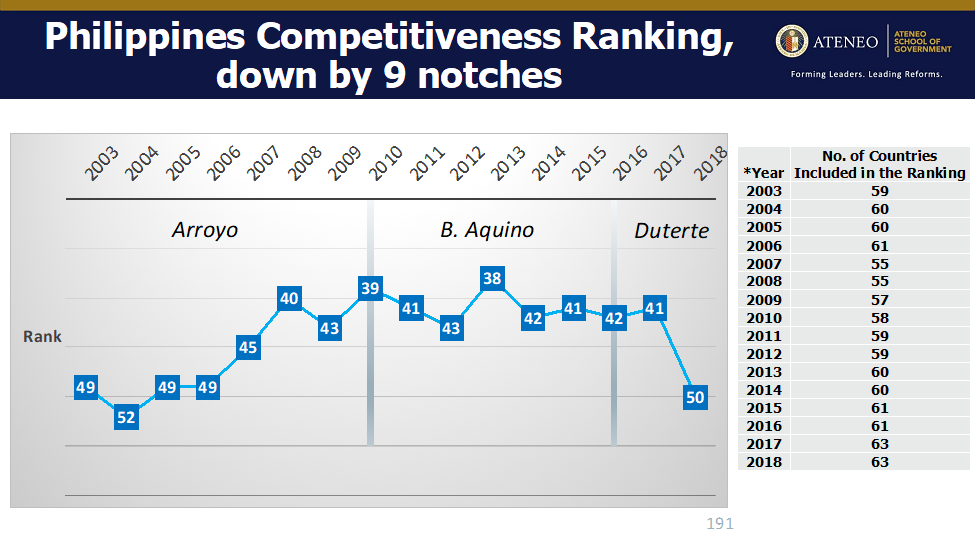

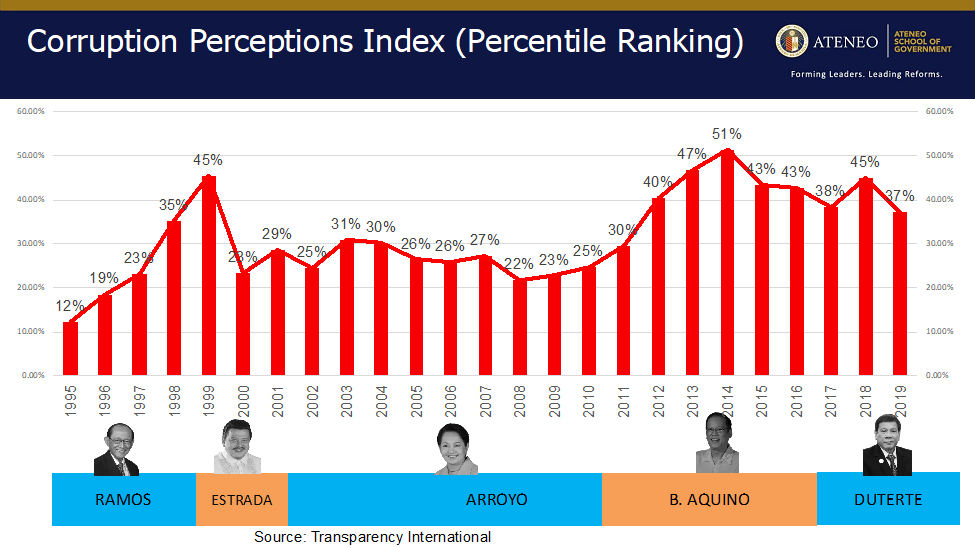

The Philippines’ competitiveness and anti-corruption rankings have also both deteriorated recently, suggesting the risk of slippage in these important reform areas (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: The Philippines dropped from 41st in competitiveness in 2017 to 50th in 2018 (out of 63 countries ranked).

Figure 3: In 2019, the Philippines was in the top 37 percent of most corrupt countries in the world.

The U.S. Millennium Challenge Corporation gave the Philippines failing marks on combating corruption and on the rule of law in November 2019. Recent research by the Ateneo Policy Center also further confirms evidence of corruption risk in the country’s infrastructure investment programs. Contractors in focus group discussions admitted that kickbacks from infrastructure projects were diminished during the Aquino administration to about 18-20 percent, but these increased again in recent years to Arroyo administration levels of up to 40 percent.

Hence, despite the best efforts of its own economic team, other parts of the Duterte administration may have done more damage to the country’s investment prospects than an A-rating can ever repair. It is critical to recalibrate the country’s policy priorities, from merely emphasizing high growth to promoting more inclusive development. It is equally critical to restore the rule of law and quash flagrant practices of political over-reach into regulatory issues such as franchise renewal and public sector contracts.

Credit rating agencies typically fail to capture these nuanced institutional and governance dimensions, instead focusing narrowly on mostly macroeconomic issues. Unsurprisingly, serious empirical research on credit ratings and economic crises suggest that ratings do not really predict these crises well. Fixating on ratings by agencies that have time and again failed to predict crises is decidedly myopic. Strengthening regulatory institutions and upholding the rule of law will be more powerful signals to investors in the longer haul.

Ronald U. Mendoza, Ph.D., is Dean and Professor of Economics at the Ateneo School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University, the Philippines.