For some, the spreading coronavirus has spotlighted China’s challenge in dealing with such issues in spite of its national strength and status, which has been on display since President Xi Jinping took power. But more broadly, the coronavirus is also a window into China’s national governance and interactions with the outside world, as well as an opportunity for key countries such as South Korea to boost their collaboration with Beijing on shared global challenges.

To be sure, the coronavirus has spotlighted Chinese government’s crisis management capabilities. Critics say that the opportunity to contain the situation early on was missed due to the country’s centralized political structure and the reporting structure between the central and provincial-level governments. Ironically, the main conclusion of the 19th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China’s fourth plenary session in October of last year was the need to modernize China’s capacity for governance.

In 2003, it took five months from the outbreak of SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) to the formation of response teams by Vice Premier Wu Yi. This time, it took nearly two months for Premier Li Keqiang to form such teams. The response time of the government has shortened, and its level of response has increased. It now remains to be seen if China’s ability to deal with this challenge has improved since the SARS outbreak 17 years ago.

The next step is the consistent development of national policy in times of crisis. The essence of China’s national ideology “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” is to achieve national prosperity, revitalization of the nation, and the happiness of the Chinese people. Many see this outbreak as resulting from sanitation issues within China, not as something coming in from the outside. But this runs counter to Xi’s promise to the people to build a “Beautiful China.” We will have to see if China will be able to achieve its 2020 goal of becoming a “moderately prosperous” society amidst the expectations of slowing economic activity in the near future.

While the economy, the fields of science and technology, and the defense sector are all growing, health and hygiene, the most basic infrastructure, lags behind. It is here that the holes in China’s “comprehensive national power” reveal themselves. China’s rising diplomatic clout, evidenced by the Belt and Road Initiative and its “new type of international relations,” has also been met with challenges. The U.S.-China trade dispute can be solved through money, and external security threats can be dealt with through China’s idea of “core interests,” but an epidemic like the novel coronavirus, aside from future trade risks, affects both China’s international image and behavior.

But the coronavirus is also affecting China’s interactions with the world more broadly. Along with SARS, this is the second outbreak of an infectious disease in China leading to anti-Chinese sentiments abroad. The epidemic is perceived to be a greater threat to the international community than China’s economic and military threats, and it remains to be seen if China is able to solve this homegrown problem itself.

Therefore, the key is to find a way that is acceptable to both the Chinese people and the international community to contain the virus early on and minimize the number of victims. If the Chinese government is able to get a firm grip on this epidemic, Xi will be able to consolidate his leadership and the national development roadmap will proceed as planned through a reorganization of national governance.

It would also be expected to have a positive effect on diplomacy and security. Currently, there have been over 420 deaths due to the novel coronavirus and more than 20,000 confirmed cases of infection. This is a higher number of deaths than those of most modern wars. China’s security policy — “an overall national security outlook,” which prioritizes internal security over external security — will focus on nontraditional security cooperation such as epidemic control. Under the concept of a “community of shared future for mankind,” China will also be more cooperative in its “neighborhood diplomacy,” recognizing the need to strengthen the international community together instead of going it alone.

For some, there may be a tendency to view international politics as a cold-blooded game. For instance, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross said on January 31 in an interview that this epidemic could be an opportunity for job creation in the United States and is good news amid the U.S.-China competition for hegemony.

South Korea, however, has a different view. The coronavirus presents an opportunity for Seoul and other countries to assist in the management of a shared global challenge and also serves as a platform for wider collaboration in medical related fields that are of concern to all citizens.

Seen from this perspective, it was the right decision for both the Korean government and the private sector to provide China with 3 million masks, and the petition for the government to ban the entry of Chinese citizens to South Korea can be conformed to meet international norms and WTO regulations.

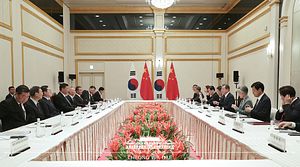

Furthermore, the vision outlining trilateral cooperation for the next 10 years between South Korea, China, and Japan that was agreed upon last December will be realized through the exchange of medical information and support between South Korea and China and between South Korea, China, and Japan.

This is not just important from the perspective of trilateral cooperation in and of itself. We can expect this to have indirect effects on South Korea’s North Korea policy and on China’s retaliatory economic measures due to the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) deployment.

If Seoul is able to carry out diplomacy in a humanitarian and well-ordered fashion, the current administration will be able to not only put its vision of a “Responsible Northeast Asia Plus Community” into practice, but also enhance its image as a partner for global cooperation.

Professor Jaeho Hwang is director of Global Security Cooperation Center at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, South Korea as well as a Canadian Global Affairs Institute fellow.