A few days before Christmas last year, a mobile phone video taken by an Indonesian fisherman in the Natuna Sea recorded Chinese vessels escorted by the Chinese Coast Guard fishing in Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ). The footage soon went viral, causing a national uproar.

Herman, a Natuna fisherman, complained in a television interview that during the night “when there are no Indonesian navy patrols, foreign fishing vessels with trawls enter [Indonesian waters] and catch fish.

“We confront them. We show them the maps that we got from the navy,” said Herman, adding that they are often chased away by the coast guard vessels that accompany the trawlers.

In recent years there have been several high-profile captures of Vietnamese and Chinese vessels engaging in illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing in Indonesian waters. These include the Hua Li 8, Gui Bei Yu 27088, and Fu Yuan Yu 831 as well as three Vietnamese vessels captured earlier this year in the Natuna Sea.

“By violating our EEZ and catching fish there, the Chinese vessels are carrying out IUU fishing,” said Mas Achmad Santosa, former head of the Indonesian illegal fishing task force (Satgas 115).

Following a meeting with the Indonesian government, China’s Ambassador Xiao Qian acknowledged that Chinese boats had entered Indonesian waters in December.

The incident came just two months after Edhy Prabowo took over the helm of Indonesia’s Marine Affairs and Fisheries Ministry from Susi Pudjiastuti. The former minister had a reputation for tough policing of illegal fishers, going so far as to scuttle captured boats.

A 2018 report found a more than 80 percent drop in foreign vessels fishing in Indonesian waters, as well as evidence of increased catches by Indonesian fishermen. It is unclear whether illegal fishing has increased with the change in minister.

The Disputed Natuna Sea

Indonesia divides its waters into 11 fishing management areas according to its Indonesian acronym: WPP. Natuna Sea or WPP 711 includes the waters around the Indonesian islands of Natuna. It is located at the western tip of West Kalimantan province, but administratively it’s a regency under the Riau Islands province east of Sumatra.

Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Indonesia claims a 200 nautical mile EEZ, including exclusive fishing rights, around Natuna. China is also a party to UNCLOS.

Novi Basuki, an Indonesian doctorate student from Sun Yat-Sen University, said that “the problem is China maintains that they have ‘traditional fishing rights’ there. Lately they also mentioned ‘maritime rights,’ although they never detail what these terms entail.”

Jakarta, meanwhile, has strongly rejected those arguments. “China’s claims to the exclusive economic zone on the grounds that its fishermen have long been active there… have no legal basis and have never been recognized by the UNCLOS 1982,” its foreign ministry said in a statement in January 2020.

Indonesia also formally lodged a complaint against the incursion at Natuna. China invited Indonesia for a friendly dialogue to resolve the dispute but Foreign Minister Geng Shuang reiterated that China has “historical rights in the South China Sea.”

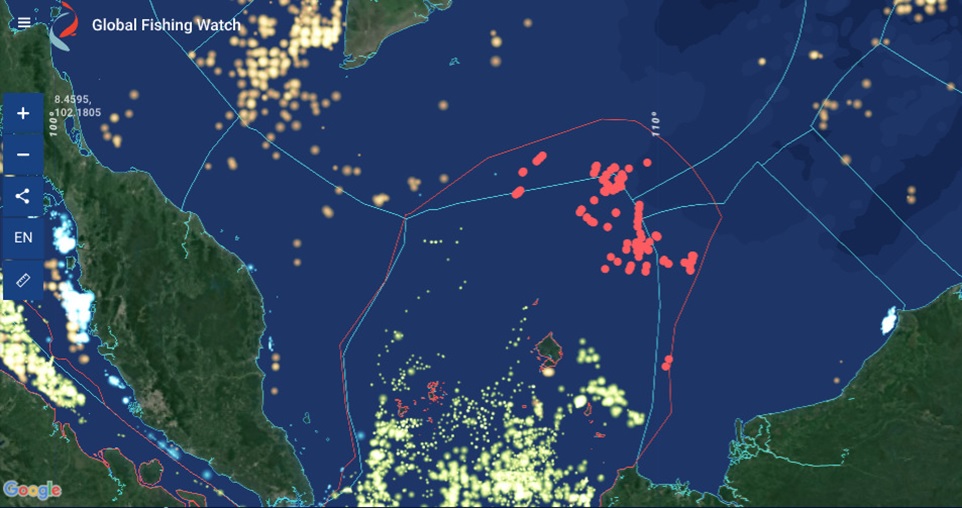

Chinese fishing and coast guard vessels (red dots) plotted on the Global Fishing Watch platform from November 1, 2019 to January 17, 2020. The yellow dots are Indonesian vessels. The red line indicates Indonesia’s EEZ.

Effects on Fisheries

According to the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Affairs, the potential fish catch in the Natuna Sea is around 961,145 tonnes. The total allowable catch is 768,916 tonnes (based on a 2018 study). The catch in 2019 is estimated to be 755,306 tonnes, although this doesn’t include illegal fishing.

Coastal environment and fisheries resources expert Yonvitner, from Bogor Agricultural University (IPB), downplays the threat of illegal fishing in Natuna to Indonesia’s fish stocks since “most of the fish in the EEZ are high migratory species that are transboundary, such as skipjack tuna, mackerel, mahi-mahi (dorado), and whales in southern Indonesia.”

However, Yonvitner said that even though illegal fishing in Indonesia’s EEZ will have little effect on the country’s fish stocks, continued incidents of illegal fishing in the EEZ will intimidate and push Indonesian fishermen’s away, narrowing their fishing ground and only allow them to fish close to the shoreline.

Trade With China

Despite the tension in Natuna, both countries are being careful to ensure bilateral trade is unaffected. China was the second biggest source of investment in Indonesia in 2019.

“Indonesia’s relationship with China has improved a lot, mainly in infrastructure investment, during [President] Jokowi’s administration,” said Basuki.

Yonvitner cautioned that in relations with China, “We have to maintain a balance, we need to have access to their market.”

In a November meeting with Prabowo, the new marine affairs and fisheries minister, Ambassador Xiao Qian noted Indonesia’s “abundant resources” and offered China’s “huge market” to Indonesia’s fishery products.

The People’s Coalition for Fisheries Justice (KIARA), an NGO advocating for the protection and welfare of fishermen and coastal communities, recorded Indonesia’s fisheries imports from China as $71.6 million, or 25 percent of the country’s total fisheries import value, in 2018.

Susan Herawati, secretary general of KIARA, said in the period between 2014 and 2019, Indonesia’s total imports from China recorded an increasing trend of 2 percent, which started with the previous minister’s administration.

She added that Minister Prabowo has not put forward any progressive plan to protect Indonesia’s marine resources. She said that “our trade relations and investment from China is not based on equality. However, the government should not see trade relations as an obstacle to protecting our marine sovereignty.”

Herawati raised concerns with both the previous and current minister. Despite being strong on law enforcement, Susi Pudjiastuti allowed Indonesia’s fisheries imports from China to soar. But on the flip side “Minister Prabowo has indicated a strong lenience towards investors to continue increasing imports and is weak on enforcement such as his move to merge Satgas 115 into the Ministry [of Marine Affairs and Fisheries],” she said.

The Way Forward

In a recent meeting with Santosa, the former Satgas 115 head, he said that Prabowo mentioned that Indonesia is “increasing patrols and that means there will be more budget allocated… especially for fuel.”

Through his newfound organization, the Indonesian Ocean Justice Initiative, Santosa is advocating for a stronger role of Indonesia’s coast guard, known as Bakamla, to see more regular patrols combined with airborne surveillance. Many of the staff at the organization formerly worked for Indonesia’s IUU fishing task force.

“Bakamla need to improve their technology to detect illegal fishing vessels, this is the priority now. They are quite sophisticated as it is, but it needs to be upgraded,” he said.

“The Chinese Coast Guard is the largest in the world. Their fleet is around 1,300 vessels and the largest [vessels] can reach 12,000 GT,” he said adding that to be able to defend Indonesia’s waters, Bakamla need to improve their technology to detect illegal fishing vessels as a priority.

“The next is presence and occupancy by our fishermen [to deter IUU fishing] all the way to the northernmost border. And this fishing effort needs to be supported by our law enforcement to protect out sovereign rights,” said Santosa.

In 2019, the Natuna Sea had 81,614 fishing vessels registered in total (including smaller boats).

China will also be amending its Fisheries Law later this year, which will require its distant-water fishing vessels to abide by stricter vessel-monitoring rules and ban them from engaging in IUU fishing.

Nabiha Shahab is a freelance writer based in Jakarta.