This week the World Bank and IMF are holding their (virtual) annual spring meetings. The COVID-19 crisis has pushed over 90 countries to ask the IMF for help. In late March, the two Bretton Woods institutions called on all official bilateral creditors — such as China — to provide immediate debt relief to low-income borrowers.

What will China do for its debtors now facing economic collapse? Some fear that a malign China will leverage this crisis to seize strategic assets. Others report that a benign China has already “wiped clean” many nations’ debt slates. “Chinese debt can easily be renegotiated, restructured, or refinanced,” said a Zambian economist.

Our research suggests that both views are far from reality. To work with Beijing to ease the pain of the spiraling economic crisis, policymakers will need to sort out the facts and the fiction about how China manages debt in troubled times.

The majority of China’s low-income borrowers are in Africa, where China made its first loan to Guinea in 1960. Today, China accounts for about 17 percent of African debt, according to the World Bank.

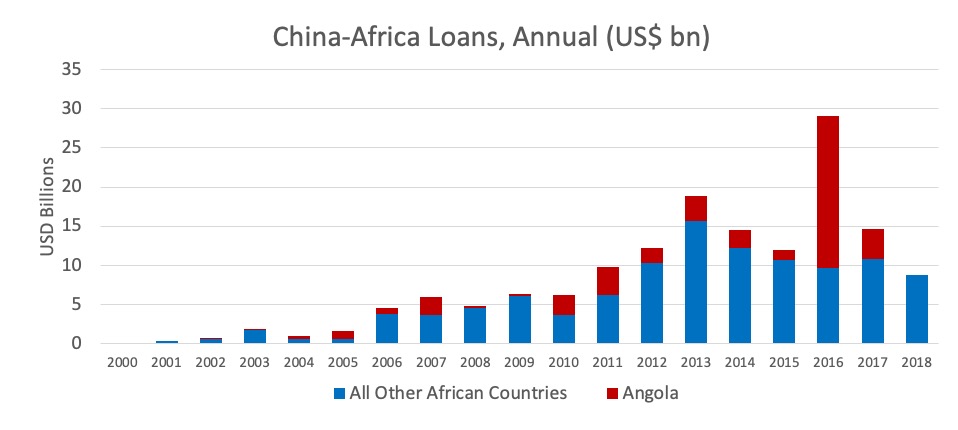

China does not publish data on its overseas lending, but our China Africa Research Initiative team at Johns Hopkins University has tracked more than a thousand Chinese loans – worth $152 billion — extended to 49 African governments and their state-owned companies between 2000 and 2018.

These are not evenly distributed. Oil-rich Angola accounts for $43 billion in signed loans — nearly 30 percent of the total for Africa. A signed agreement with a Chinese lender is not the same as a debt, however. For example, as of 2017, China had agreed to lend Nigeria $5.3 billion for transport, IT, and power projects, but had disbursed just $2.5 billion. Furthermore, our figures do not account for repayments. Angola has repaid at least $16.7 billion of its Chinese loans.

Yet in the current crisis, any level of debt risks being unsustainable. What is China likely to do?

Our team recently examined dozens of Chinese overseas debt restructurings between 1980 and 2019 and nearly a hundred cases of debt cancellation. Our findings run counter to much of the conventional wisdom.

Myth #1: China frequently cancels debt

A recent study of Chinese debt relief concluded that China’s debt write-offs were “common.” One financial analyst called Beijing a “free money machine,” saying (erroneously) that over half of China’s debt relief recipients had their debt written off completely between 2000 and 2018.

Yes, China has canceled more than $4 billion in low income countries’ debt since 2000. However, these canceled debts — more than 376 of them — were nearly all from a small category of Chinese lending: interest-free, foreign aid loans that had reached maturity without being fully paid off. In Africa, interest-free loans today average $10 million and make up less than 5 percent of Chinese lending.

Myth #2: Chinese debt negotiations are easy

China does not impose the economic conditions required by the IMF or the World Bank, but the process of debt relief is not automatic. In Beijing, a committee led by China’s Ministry of Finance and involving the Ministry of Commerce, China Exim Bank, and China Development Bank carefully considers whether applicants for relief are truly unable to service each troubled loan on its original terms.

The Republic of Congo’s successful $1.6 billion debt restructuring in 2019 provided new terms for just eight of the country’s two dozen Chinese loans. This complicated, loan-by-loan scrutiny differs from Paris Club debt workouts, which usually treat the entire debt stock.

Furthermore, calls for “China” to provide debt relief overlook the fact that there are now multiple Chinese lenders. We found more than 30* Chinese banks and companies loaning money to African governments.

In Iraq, China joined with other countries in a United Nations-sponsored effort to cancel debt in 2007. Beijing forgave all the official debt owed to the Chinese government. But Iraq was also on the hook to Chinese companies for some $8.5 billion in commercial debt. It took another three years of separate negotiations for 80 percent of this to be written off.

Myth #3: China will seize strategic assets in lieu of loan payments

We saw no evidence of asset seizures in Africa, or indeed, anywhere among Chinese borrowers in debt difficulties. In the much misunderstood case of Hambantota port in Sri Lanka, a newly elected government facing a balance of payments crisis that was not Chinese in origin privatized its Chinese-financed port to a Chinese investor in 2017. This brought in over $1 billion in foreign exchange. Similarly, debt-distressed Republic of Congo concessioned its 535-kilometer Chinese-financed highway to a Congolese-Sino-French consortium, which now operates it as a toll road.

The Trump administration has stoked fears about countries losing their sovereignty through public-private partnerships like these. Instead, we should be encouraging more of them. Equity investments are a smart way for countries to finance the operation of badly needed infrastructure, while also helping repay loans.

The challenges outlined here make it unlikely that we will see Beijing agree to real and wide-ranging debt relief this week. At the end of 2018, China itself owed $1.96 trillion in foreign debt. As a former China Exim Bank official told me: “if African borrowers don’t pay us, we still have to pay our bondholders.”

As the economic and financial toll from COVID-19 becomes apparent, Chinese loans — and the possibility of debt relief — will continue to be in the headlines. Making sense of what China can and can’t offer requires taking a hard look at some deep-seated myths about Chinese lending.

*This figure has been updated.

Deborah Brautigam is Bernard L. Schwartz Professor of International Political Economy and Director of the SAIS China Africa Research Initiative at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS).