As the Trump administration’s first term comes to a close and the United States hurtles toward its next presidential election, the coronavirus outbreak has gripped national and international attention, spawning debates and discussions on what a post-COVID-19 world order will look like. While the virus’ impact on a host of bilateral and multilateral engagements is being assessed, one relationship that is gaining even more attention is that between the two most powerful countries in the world: the United States and China. A war of words and a blame game between the two countries has occupied the headlines. The epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak has shifted to the U.S. while China projects the image of a country that has successfully combated the virus and is ready to help the world. For example, China has sent doctors and medical supplies to countries around the world even as the European Union and the United States are trying to consolidate their own domestic responses to the global outbreak. This comes at a time when the Trump administration has been facing a lot of criticism for its inefficient handling of the pandemic.

The political leadership in the United States has, for one, accused the Chinese government of bringing about the global pandemic, with its questionable handling of the public health crisis in China. Beijing’s dogged determination to take advantage of the crisis, to bolster its claim to global leadership and Trump’s insistence on calling it the “Chinese Virus” for weeks opened new faultlines in a great power dynamic that was already confrontational. The Chinese government initially signaled its displeasure at U.S. apathy over the initial stages of the virus – criticizing Washington for evacuating its citizens without offering any help (although the U.S. CDC reportedly offered to send a team to help as early as January 6). On social media, Chinese diplomats strongly signaled their anger and some even went as far as to back the conspiracy theory that the coronavirus was a bioweapon manufactured in American laboratories.

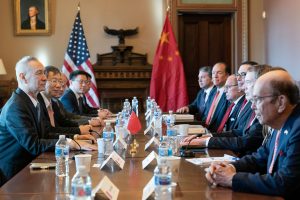

The bilateral spat between the two most powerful countries in the world comes amid the unfinished business of the trade war. The Trump administration started its term by accusing the Obama administration for failing to put China in its place and accommodating its rise to the detriment of U.S. global leadership. Throughout Trump’s election campaign back in 2016, he stressed what he saw as the threat from Chinese manufacturing stealing American jobs. Trump’s election rhetoric translated into policy when he became president. June 2018 saw the first round of tariffs from both sides and since then, the United States has imposed tariffs on Chinese goods worth more than $360 billion and China has imposed tariffs on American goods to the tune of $110 billion. A “Phase One” deal between China and the United States was settled in mid-January, but the pandemic has overtaken what gain that represented and upset its terms.

Recent reports point to a China that seems equally focused on ramping up its power projection in the Western Pacific, while the world is grappling with containing the COVID-19 outbreak. America’s call for a “free and open Indo-Pacific” in operational terms has meant more unfettered access to the waters of the Western Pacific, the geopolitical hotspot of the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy. China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea and its militarization of the space has been a matter of concern for a number of Southeast Asian countries, some with close ties to the United States. China’s ambitions for sea control and sea denial in the region are perceived by the United States as an affront to its freedom of navigation, which it asserts with FONOPS across the area and has been a matter of contestation and confrontation between the Chinese and the U.S. Navy.

Chinese military drills in the South China Sea, in response to U.S. FONOPS missions, including a joint military exercise with Cambodia, a Southeast Asian country hugely depended on Chinese aid, have been reported. The busy waterways of the South China Sea have been viewed as one of the most probable sites of a major military confrontation. While the U.S. military and its force posturing, aiming to sustain its primacy in the Western Pacific, has been unchallenged for a long time, the consequences of China’s rise have fundamentally altered the dynamics. What further complicates the great power dynamics between the two, and what would probably determine the complex dynamics of a Cold War 2.0 is the fact that China is the most consequential development and economic partner of a number of countries that prefer the U.S. as their security partner.

The U.S. and its Indo-Pacific partners are wary of China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and have scrambled for a credible response. More recently, the Blue Dot Network has been proposed among American partners, to perhaps offer an alternative through “a multi-stakeholder initiative that will bring governments, the private sector, and civil society together to promote high-quality trusted standards for global infrastructure development.” A number of U.S. government documents including the U.S. National Defense strategy, the National Security Strategy and the National Military Strategy have reflected a growing sense of threat perceived from a rising China. China has been called out for engaging in predatory economic practices and along with Russia has been clubbed as near peer competitors challenging American primacy globally and China more particularly in the Indo-Pacific.

The confrontational streak is reflected in non-military dimensions as well. Over the last few years, the United States has raised concerns over Chinese tech companies which remain private but have deep links to the Communist Party. With 5G technology for example, the U.S. government has blocked companies like Huawei and ZTE because of apprehensions over national security threats and has pressured its allies to do the same. On the other hand, the numbers of Chinese students in the United States is falling dramatically. The United States recently suspended its Peace Corps program to China, which had been active since June 1993. There have also been minor diplomatic incidents as the United States last year expelled two Chinese diplomats and in retaliation, the Chinese government amended the rules by which American diplomats could meet with local officials.

The U.S. is fighting a war against COVID-19 unlike any it has seen in its history and China leaves no stones unturned as it creates counternarratives to its image as a country that irresponsibly handled the COVID-19 outbreak in its own soil leading to the global pandemic. At a time when calls for global cooperation and coordination are being heard louder than ever before, U.S.-China great power dynamics are taking a new shape, and unfortunately does not demonstrate signs of a real thaw in the relationship. All signs point to a road that will create new faultlines of confrontation in a relationship that is consequential for global order and governance.

Monish Tourangbam is a Senior Assistant Professor at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India.

Hamsini Hariharan is a Yenching Scholar at Peking University and a journalist.