On February 4, when a novel strain of coronavirus – officially dubbed SARS-CoV-2 — was raging in Wuhan, a letter to the editor appeared in the journal Cell Research. Written by scientists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, the letter outlined the promising findings of a recent experiment. In a test tube, coronavirus was “potently blocked” by two drugs: remdesivir and chloroquine.

The letter was the first indication that chloroquine, a widely available and cheap malaria drug, might prove useful in the fight against COVID-19, as the disease caused by the new coronavirus strain came to be known. Notably, one of the authors was China’s “bat woman” Shi Zhengli, a formidable virologist and coronavirus expert who had assembled an encyclopedic database of bat-borne viruses over her decades-long career. She also led the team that first sequenced the genome of SARS-CoV-2 and identified the virus as a close relative of a coronavirus found in horseshoe bats of Yunnan.

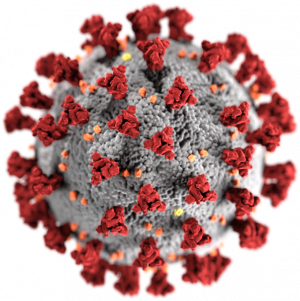

What the virologists observed under the microscope was chloroquine’s powerful virus-repelling properties, which had come to light soon after the 2003 SARS epidemic. How chloroquine works is a bit of a mystery even to scientists, but what’s clear is the drug operates at multiple levels to prevent a virus from hijacking a cell. Coronaviruses need an acidic environment to enter human cells. Chloroquine, being alkaline, blocks the virus by raising the body’s pH level. The drug also prevents the spike proteins on the outside of the virus from binding with a cell receptor by thwarting a process called “glycosylation.” More generally, chloroquine stimulates the immune system, which indirectly boosts the body’s ability to fight off a virus. Significantly, the drug provides this protection at two stages — before and after the cell is infected — indicating that it can be used as a prophylactic.

Wuhan virologists confirmed the “before and after” virus-blocking effects of chloroquine were clearly evident in cells infected with novel coronavirus. They recommended clinical tests in humans, noting that the immune-boosting properties of the drug may “synergistically” bump up the antiviral effect in patients suffering from the disease, which had yet to be named. The authors later wrote in Cell Discovery that chloroquine “appears to be the drug of choice for large-scale use due to its availability, proven safety record, and a relatively low cost.”

A lot has changed since the letter was first published. The Wuhan outbreak is now a pandemic and the disease has a name: COVID-19. The United States, which had more than 4,000 deaths at the end of March, is the new epicenter.

Chloroquine recently became one of the most hoarded drugs on the planet after U.S. President Donald Trump declared he was a “big fan” of hydroxychloroquine, a derivative that showed promise in a small study by French doctors. Scientists, physicians, and public health officials are alarmed that a drug prescribed for autoimmune diseases like lupus was being touted as a “cure” for COVID-19 based on scant clinical evidence. The debate began taking on political overtones. Chloroquine is turning into a “partisan food fight,” warned Ashish Jha, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute: “All of us would love for it to be effective. The problem is that we don’t know if it is.”

As the United States and Europe struggle to contain the virus, it’s worth noting that two months ago virologists in China urged the medical community to begin clinical trials on chloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19. The only follow up so far came from two small studies in China and France based on case studies of about 150 patients — but these were not randomized double-blind clinical trials, which are the norm for drug testing.

The medical establishment in the United States has been reluctant to endorse chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine for the treatment for COVID-19 due to the paucity of clinical data. Dr. Otto Yang, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California, Los Angeles explained in an interview with TIME that promising in vitro experiments don’t always live up to expectations: “The problem is that what happens in the lab often doesn’t predict what happens in a patient.”

The World Health Organization belatedly launched a large-scale drug trial two weeks ago. Both chloroquine and remdesivir will be tested on patients in Europe.

Meanwhile, doctors in New York City and around the world are quietly using chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine on an off-label basis for desperately ill patients. Time will tell if their findings will confirm what virologists in Wuhan noticed nearly two months ago.

Sribala Subramanian writes on environment and health, focusing on Asia. Her work has been published in The Guardian, The Wire and Eurasia Review. Follow her on Twitter: @bsubram.