On August 14, 2019, amid the height of Hong Kong anti-extradition bill protest, a group of young people from mainland China climbed over China’s Great Firewall and flooded social media platforms including Facebook, Twitter and Instagram with memes, comments, and posts. They condemned Hong Kong protesters and hailed China as “the best in the world.” This action, officially known as “Fangirl Expedition” as it was mobilized by fan communities in China, won praise from Chinese authorities. Chinese Communist Youth League wrote on Weibo that the expedition had achieved overwhelming success, and that fangirls’ patriotic actions were orderly, rational and deeply touching.

Recently, China’s young nationalists waged another expedition on Twitter, except this time the rampaging army collapsed unexpectedly in front of their target, the Thais, and their patriotic action was scolded — though tactfully — by the Chinese authorities as “a low-brow farce.”

Social media is flooded with #nnevvy memes showing Thai netizens using self-deprecating humor to deflect attacks from Chinese trolls. Whereas China has spent billions and decades building its “soft power,” Thai people with high EQ did so in a few days. True masters in PR. 🇹🇭 pic.twitter.com/Um7AzmnJXJ

— Jason Y. Ng (@jasonyng) April 13, 2020

The War

The latest incident all started with Thai actor Vachirawit Chiva-aree, or Bright, who “liked” a post retweeted by his girlfriend (@nnevvy) saying that the Institute of Virology in Wuhan has more than 1,500 strains of virus, and suggesting that the virus might have been leaked from the lab in Wuhan. This irritated Bright’s Chinese fans, who saw the post as “racial discrimination” and spreading a “rumor about COVID-19.” Offended, they went over the Great Firewall of China and flooded @nnevvy’s Twitter. The warfare escalated after some Chinese fans dug out a post from two years ago by @nnevvy, which stressed that her outfit on that day was “Taiwan-girl style,” instead of “Chinese-girl style.” This later proved to be a misunderstanding caused by Google translate, but nonetheless, the Chinese cyber army — which by this point has expanded outside of Bright’s fanbase — was convinced that @nnevvy is a td (taidu, or Taiwan-independence supporter), and they decided to teach her a lesson.

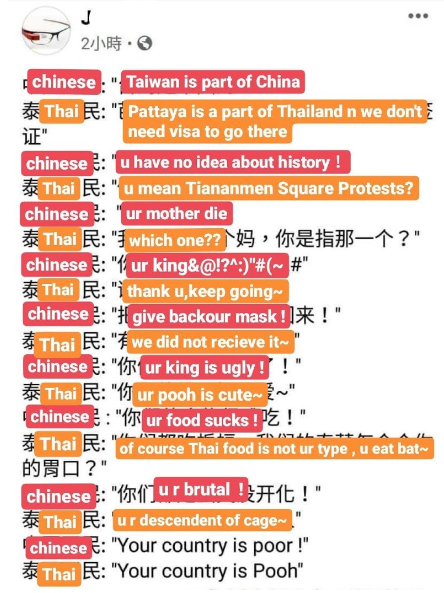

Apart from asking for an apology, their strategies mostly included insulting Thai government leaders and royals, mocking Thailand’s less developed economy compared with China, and educating them that Taiwan has always been a part of China. When that did not work, some started throwing curse words at the Thais (this was met with disagreement from some of their fellow soldiers, stressing that “We must be rational. Do not use profanity!”). The Thais, on the other hand, were immune to all insults, and turned whatever was thrown at them into a better joke.

Inside the Firewall and on Weibo, angry nationalists flooded the official account of the Tourism Authority of Thailand (@泰国国家旅游局), accusing them of not being able to control what Thai netizens have done to China. On Douban, someone posted detailed instructions on how to report internet users to Thai authorities, calling for all Chinese to stop confronting Thai netizens on Twitter and “Let their own police deal with them.”

Inside the Firewall and on Weibo, angry nationalists flooded the official account of the Tourism Authority of Thailand (@泰国国家旅游局), accusing them of not being able to control what Thai netizens have done to China. On Douban, someone posted detailed instructions on how to report internet users to Thai authorities, calling for all Chinese to stop confronting Thai netizens on Twitter and “Let their own police deal with them.”

Now back to the battlefield on Twitter, #nnevvy soon became a trending topic, and it didn’t take long before Joshua Wong (@joshuawongcf), a Hong Kong activist and one of the major targets of the 2019 Fangirl Expedition, joined the Thais by posting “Hong Kong stands with our freedom-loving friends in Thailand against Chinese bullying!” Hong Kong and Taiwanese netizens’ entering the war was an alarming signal for some: “Wait, we are being used by td and gd [Taiwan-independence supporters and Hong Kong-independence supporters]! Anti-China forces are taking advantage of this!”

Fandom Nationalism

While some on Twitter believe these trolls are wumao, i.e. those who get paid by the Chinese government to post pro-China comments online, the reactions from netizens on Chinese social media, especially from the fans of Bright, show that such expeditions are more spontaneous movements mobilized by nationalists who are genuinely offended by tweets that go against what they have been taught inside the Great Firewall.

What we are witnessing here, then, is a curious convergence of pop culture fans and nationalists. American scholar Henry Jenkins has long argued for the political potential of fan consumers, and in Chinese context, this emerges as what Liu Hailong has called “Fandom nationalism.”

One might reasonably assume that Bright’s fans should find themselves stuck in between their beloved idol and the moral obligation to be patriotic. But, as it turned out, this was not that a difficult decision to make: “There is no place for idols in front of my country,” proclaimed the subtitle-makers of the TV drama where Bright played the leading role. Another fan wrote, “It’s fine if you decide to give up Chinese market and your Chinese fans…But how can you just sit there doing nothing when your girlfriend is insulting China…A country’s sovereign integrity is the bottom line!” A poll on Weibo with 35,000 respondents also suggests that as many as 91 percent of Bright’s fans will stop “stanning” him because of this incident.

As a form of online activism, fandom nationalism often takes the shape of “online expeditions.” The ways in which such expeditions are organized, the expression style used, and the discursive strategies employed all highly resemble those of fan communities. For example, in large-scale expeditions such as the 2019 Fangirl Expedition, there is a clear division of labor. There are translation groups, photoshop groups, intelligence groups, and groups that are responsible for reporting “enemies.” Such an organizational pattern is already embedded in fan communities. It is part of their day-to-day activities to support their idols in competition with other pop stars, by creating as much positive content and trending topics as possible while attacking and reporting negative content. The goal is for their idols to win more popularity, and hence become more valuable commercially. “This is the only thing I can do for him/her,” fans would usually say.

This time too, the participants set up translation groups for Chinese, English, and Thai. When they realized the Thais had clearly got the upper hand, and most appallingly Hong Kong and Taiwanese were involved too, opinion leaders among Bright’s fan community asked for all participants to switch their strategy. Instead of directly confronting the “enemy” under the hashtag #nnevvy, they would post positive content about China, such as food and natural scenery, under the hashtag #China.

While it has been argued that this easily provoked, touchy nationalism is largely the result of the CCP propaganda and censorship, nothing facilitates nationalist sentiment better than fan communities. A fan community is essentially an “imagined community” based on obsession with an object, and the obligation that comes with that obsession to promote and/or defend the fan object. It follows the logic of insiders versus outsiders, and is positioned against an imagined Other, be it another idol and its fanbase, or those who post negative things about our idol. Such dichotomous logic perfectly matches the kind of worldview China holds in international relations: a realist perspective that sees the state as a rational actor in itself, and the international system as an anarchic one where states compete with each other for a better chance of survival.

China sees itself as besieged by “anti-China forces,” and so do Chinese young nationalists. In this Twitter war, “China” was imagined as an idol that had been bullied by others, and thus “we,” as his fans, must rise and defend him.

Patriots and #nmslese

This incident also reflects the long-time dilemma in the way China manages nationalist sentiment among its population: nationalism needs to be encouraged to enhance legitimacy, but when nationalists go too far they have the potential to threaten the regime itself.

In an effort to mitigate the tension without breaking its own supporters’ hearts, the CCP finds someone else to blame: anti-China forces. An article published on Wednesday by the Communist Youth League explains that it was not the Thais’ intention to “insult” China. Instead, the Thai media’s copy and paste of “Western media” — the puppet of the imagined Other, the West — on China-related issues supposedly led many Thais to consider Taiwan an independent country. The article further claims that the real threat behind this internet fight is those Taiwan-independence supporters and Hong Kong-independence supporters who “fear the world is not chaotic enough” and are seeking to undermine the friendly relations between China and Thailand — and by doing so threaten China’s peripheral security.

According to this logic, those who went for the expedition are still patriots, and the fault is all the West’s. This mindset has proven to be especially exploitable when CCP legitimacy is under threat. In August 2019, the Fangirl Expedition targeting Hong Kong protests received high-profile endorsement from the Chinese government. State media including People’s Daily, Global Times, and the official Weibo account of the Chinese Communist Youth League all gave generous compliments to the fangirls, encouraging them to carry on such patriotic actions. Similarly, during the COVID-19 outbreak, through playing on conspiracy theories, China has tried to shift the blame to “anti-China forces,” provoking nationalism at home as a means to resolve the legitimacy crisis brought about by its initial mishandling of the outbreak.

By Wednesday, related hashtags including #BrightGirlfriend and #ThailandInsultsChina had been taken down from Weibo “according to laws.” A Party-managed newspaper, Reference News, published an article calling an end to this “low-brow farce,” stressing that China and Thailand have always had a good relationship. In the end, the nationalists, or patriots as they are called in China, might be naïve, but the real malice is always the good old “anti-China forces.”

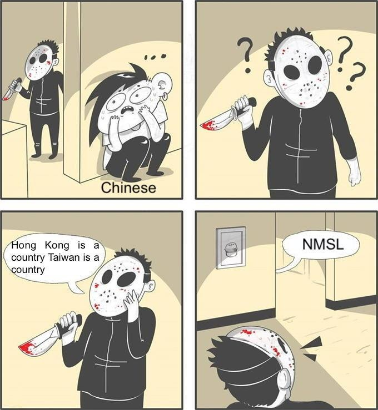

Outside the Great Firewall where the CCP propaganda and censorship do not reign, these patriots are viewed as nothing more than brain-washed mobs. Thai netizens, together with their fellow fighters from Taiwan and Hong Kong, ridiculed Chinese trolls as #nmslese, for their inability to produce any concrete arguments and their obsession with throwing curses, the most infamous of which is “NMSL,” an acronym for the Chinese phrase literally meaning “Your mother is dead.”

Outside the Great Firewall where the CCP propaganda and censorship do not reign, these patriots are viewed as nothing more than brain-washed mobs. Thai netizens, together with their fellow fighters from Taiwan and Hong Kong, ridiculed Chinese trolls as #nmslese, for their inability to produce any concrete arguments and their obsession with throwing curses, the most infamous of which is “NMSL,” an acronym for the Chinese phrase literally meaning “Your mother is dead.”

In fact, the very existence of the Firewall implies the inescapable conclusion that this interaction was a “fight,” as opposed to a dialogue. Being a “wall,” China’s Great Firewall functions symbolically as a defensive infrastructure. It blocks harmful information from the outside, and preserves the purity and safety of the internet on the inside. In this sense, the Expedition has to be an “expedition,” an adventurous action that aims to attack, conquer, and hegemonize.

The Chinese propaganda machine, from the education system to the censorship to the Firewall itself, is nurturing an army that rampages around, witch-hunting anyone who dares to criticize China. Chinese young people might one day find themselves so attached to the hashtag #nmslese that any constructive dialogues between them and those outside the Firewall would become an arduous effort to decouple with their own country.