Starting as an insignificant spat, the recent online war of words between Chinese and Thai netizens has caught the headlines of international news outlets, including CNN and Foreign Policy magazine. Even though the Beijing embassy in Bangkok referred to this squabbling as “online noise,” the embassy jumped into the viral argument rather than ignoring such unpleasant words. This unforeseen action instantly heightened the humorous but highly political trolling on Twitter and other social media platforms. Hong Kong’s pro-democracy activists and Taiwanese politicians have also engaged in this altercation, which, in turn, has further angered Beijing.

How did this turn into a trend? More importantly, what does this wave of “online noise” tell us about the future of China’s relations with Thailand?

All the noise arose from an online fracas when female Chinese fans of Thailand’s same-sex romantic dramas were annoyed by the fact that Vachirawit Chivaaree — also known as Bright, a Thai actor who starred as a lead character in “2gether: The Series” — actually had a real-life female girlfriend. They became angrier when Chivaaree retweeted a post in which he shared photos with a caption that described Hong Kong as a country. Although Chivaaree apologized to his fans on the mainland for his “thoughtless” action, they subsequently accused him and his girlfriend, Weeraya Sukaram, of being pro-Taiwan. The ongoing spat set social media ablaze when Chinese fans were outraged at Sukaram’s retweeting of a message questioning whether the COVID-19 virus originated in a Wuhan laboratory. This situation precipitated a flare-up not only between fans but also among social media users in the two countries. Users started bombarding social media with abusive comments against Sukaram using the hashtag #nnevvy, which was adopted because of her Twitter and Instagram handle, @nnevvy.

The outpouring of nationalist slurs and hatred online was fuelled by China’s state-controlled news media. For instance, an article in the Global Times, a Communist Party-affiliated newspaper, quoted one popular comment stating, “There is no such thing as an idol when it comes to the important matters of our country.” Several Chinese “keyboard warriors” breached the national firewall to act as trolls on Twitter, a social media platform banned in the mainland, trying to “teach Sukaram a lesson” — but not by simply attacking her as an individual. Instead, they hurled insults at Thailand’s monarch, prime minister, state, and people. Ironically, Chinese trolls were confused by reactions from Thai Twitter users, who did not consider what the Chinese were insulting as being important. Many Thais seemed to gleefully enjoy having someone else mocking their nation.

Online trolling by China’s Twitter users subsequently started to backfire. Not only did the Thai Twitter users laugh off the tweets that mocked them by making hilarious, self-deprecating jokes, they also re-packaged the jokes into a string of increasingly clever satirical memes. The hashtag #nnevvy was soon in heavy use by Thai users who wrote witty but self-mocking words about themselves, and hilarious yet highly political memes targeted back at the Chinese trolls. For example, while some Thai users poked fun at the Chinese trolls by using Winnie the Pooh, a cartoon character, as a stand-in for Chinese President Xi Jinping, others hurt the feelings and pride of China’s Twitter users by supporting Hong Kong’s independence and Taiwan’s quest for international recognition.

Thai netizens quickly realized that they were not alone in striking back at China’s nationalist trolls. Social media users from across East Asia, from Hong Kong through Taipei to the Philippines, enjoined the online meme war with Thailand against China. Hong Kong’s pro-democracy activists came onto the scene. Joshua Wong tweeted his support of “…our freedom-loving friends in Thailand against Chinese bullying” while his colleague Nathan Law tweeted, “So funny watching the pro-CCP online army trying to attack Bright….What they don’t understand is that Bright’s fans are young and progressive, and the pro-CCP army always make the wrong attacks.” Taiwanese politician Cheng Wen-Tsan also jumped on the trend by expressing his gratitude to the Thai people via Twitter for travelling to Taiwan — and included the hashtag #nnevvy. This effected a virtual coalition called the “Milk Tea Alliance,” an informal term coined after a popular drink in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Thailand. Subsequently, the hashtag #MilkTeaAlliance flooded Twitter and other social media.

The “Sino–Milk Tea war” in the Twitterverse would be, perhaps, no more than the latest fad among like-minded netizens had the Chinese embassy in Thailand not stepped in. Despite referring to the quarrel as “online noise,” the embassy issued a lengthy statement in Chinese, Thai, and English, stressing that the One China principle was irrefutable. The embassy’s statement stated that comments made by Thai users simply reflected their “bias and ignorance.” It underscored the long-tested friendship between China and Thailand, calling the two “one family.” Further, in a Thai-language version, it recalled the motto that “China and Thailand are not others, but brothers” (Chin Thai chai uen klai phinong kan). The statement promptly caused the embassy’s Facebook page to be stormed by Thai trolls. However, what further surprised observers was the embassy’s persistent habit of “feeding the trolls” by replying to several comments that had been solely intended to create a disturbance.

The Chinese embassy’s statement only fanned the online flames. Its decision to step in has surprised many Thais. For them, what happened was nothing but another senseless spat among fans; it is, therefore, not supposed to be the embassy’s business. Thai netizens pointed out that there had been an annual, online argument between Thais and Filipinos about beauty pageants, yet Manila’s embassy in Bangkok has never stepped in to address the harmless internet squabbling. The embassy’s statement not only made Thais perceive China as “immature,” but also made some of them feel “intimidated.” Further, almost simultaneously, Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen issued a tweet sending best wishes to the Thai people for the Thai New Year in both Thai and English. Though Tsai’s tweet made many Thai users feel positive toward Taipei, it also exacerbated their attitudes about Beijing, causing them to strike back at the embassy’s move by flooding social media with a new hashtag in Thai — cha nom khemkhon kwa lueat (“milk tea is thicker than blood”). Moreover, the hashtag #StopMekongDam gained popularity after Thai netizens asked Beijing’s embassy, through its Facebook page, why was China blocking the upper Mekong’s water using Chinese hydropower dams, preventing it from flowing downstream to Thailand, causing widespread drought there. After all, the netizens said, aren’t China and Thailand “family”?

Although the viral Sino–Milk Tea war of words has been waning at the time of this writing, the U.S. embassy in Bangkok has taken the opportunity to promote its public diplomacy through the embassy’s Facebook page, portraying itself as a responsible, mature, and truly great power to Thai audiences. Recently, the embassy released an op-ed by Michael George DeSombre, the newly appointed U.S. ambassador to Thailand, about Mekong River issues. In his article, he asserted that the Mekong River is shared, transboundary river, and does not belong to any single country. DeSombre also said that the drought in the downstream basin was caused by the dams built upstream and supported efforts calling for greater investigation of dam operations. This prompted the Chinese embassy to fiercely deny such claims, precipitating an online war of words between the two embassies.

The #nnevvy and the Sino-Milk Tea wars are a short-lived trend, and certainly in the short run, the two countries’ ties have not been affected. The incident, however, has revealed implications for the future of Sino–Thai relations, something that both scholars and policymakers cannot overlook.

The popular response of Thai users to the statement released by the Beijing embassy demonstrates that younger generations of Thais have not seemed receptive to the government’s motto, “China and Thailand are not others, but brothers.” This is likely to be truer for urban middle-class Thais, who spend most of their time on social media, especially young adults who tend to be politically liberal, if not pro-democracy. Moreover, the latter describes most fans of the country’s same-sex romantic dramas – which, again, was the origin of the spat. As the personal is political (to paraphrase the popular feminist slogan), the personal always affects China’s power in Thailand. The impact of the personal on Sino–Thai ties is evident in the public sentiment, specifically in the attitude of the Thai middle class.

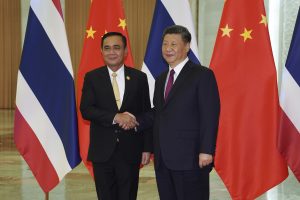

During the Asian financial crisis, middle-class Thais praised and were thankful for Beijing’s decision not to devalue its currency, thus upholding the rhetoric of kinship between China and Thailand at the people’s level. But after Xi Jinping assumed power, the image of China in Thailand’s public opinion gradually deteriorated because of both internal and external factors. Internally, urban, middle-class Thais, especially the younger generations, have doubted and felt disappointed by the unpopular Thai government, installed after the 2014 coup, whose direction in foreign policy appears to lean on and accommodate China. For example, the general public in Thailand appears to be deeply skeptical about the China–Thai railway agreement, with its high interest rates, that was pushed forward by the Thai government, questioning whether it could be a debt trap. The Thai economy’s high dependence on Chinese tourists has, in turn, fuelled anti-Chinese feelings in the country. The public has witnessed, and many have been affected by, the sharp decline in Chinese tourists, likely a punishment imposed by Beijing after General Prawit Wongsuwan made an outspoken remark following a tour boat accident off Phuket in 2018.

Externally, the global pandemic of COVID-19 that originated in Wuhan has rapidly intensified anti-Chinese sentiment in Thailand. China’s coronavirus culpability and its donation of defective medical supplies have reaffirmed the deeply embedded bias among Thais toward the Chinese people and made-in-China products. The negative prejudice is evident in the language used in daily life. For instance, Thais usually describe cheap, low-quality products as being of the “Shenzhen standard” (mattrathan Soen Choen).

The #nnevvy and the Sino–Milk Tea wars have accelerated China’s failing power in Thailand. The younger generations of Thais no longer perceive China as a benign big brother. Further, as a new generation of middle-class Thais will soon replace those currently ruling the country, their changing attitudes about China and the Chinese people do matter. The latest online war of words might be better perceived as a political message to policymakers in Beijing about the future. Rising anti-Chinese sentiment has started damaging the people-to-people basis of Sino–Thai ties, often claimed to exist by both the Chinese and Thai governments.

In fact, policymakers in Bangkok have perceived China as a long-term threat since the mid-1980s — a fact revealed through declassified documents from both Bangkok and Washington. Whatever the officials may say, this tone has overshadowed the country’s perception of its big brother.

It is not the author’s intent to be pessimistic about a murky future of China–Thailand relations. But in international politics, there is no such thing as “brothers” nor “blood is thicker than water.” The Sino-Thai relationship is not an exception.

Poowin Bunyavejchewin is a senior researcher at the Institute of East Asian Studies (IEAS) at Thammasat University, Thailand.