China has taken advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been dominating headlines around the world, to reinforce its grasp on the South China Sea. While Western media is now preoccupied by the U.S. protests, Beijing will likely continue to take advantage of the fact that the eyes of the world remain focused elsewhere.

In the South China Sea, these past six months were marked by four distinct events. First, there was the Chinese Coast Guard’s aggression in sinking a Vietnamese fishing vessel. Second, the Chinese survey ship Haiyang Dizhi 8 went trolling for oil in the Malaysian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) north of Malaysia but within the nine-dash line that encompasses China’s claimed waters. Third, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) stretched its legs and conducted sea trials with the Liaoning aircraft carrier. Finally, Beijing announced the creation of two new administrative districts in the South China Sea, covering disputed maritime features.

Looking into the summer with major Chinese military drills on the horizon, it can be expected that Beijing will continue to make advances that tighten its grip within the first island chain.

While deployed in the South China Sea on the USS America this spring, I would make it a point to go to the weather deck every day and take in as much as I could observe. One early morning, while we were south of the Paracel Islands, the water was heavily congested by small, brightly covered ships all the way out to the horizon in every direction. Fortunately, I packed binoculars. While our large amphibious ship weaved meticulously through the traffic I was able to discern that each of these vessels was casting fishing equipment into the sea while proudly flying the Vietnamese flag. After conversing with the watch sailors I gathered that at this time of the year the South China Sea, which the Vietnamese refer to as the East Sea, is always congested with Vietnamese fishing ships.

All of this occurred while our ship was shadowed by the PLAN, which is routinely done during freedom of navigation operations. But we did not see the Chinese Coast Guard (CCG), which would surely have chased away these fishermen. The key takeaway from the sheer number of vessels present during this time of the year is that the potential for a dispute is constant during the fishing season. However, we rarely see what happened in April with the sinking of one of these fishing ships that happened to come across the CCG. Beijing has apparently tasked its Coast Guard to patrol with a purpose this year.

Then, while COVID-19 spread aboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt aircraft carrier and it returned to Guam, the news hit that the Haiyang Dizhi 8 survey ship, accompanied by an armada of CCG and PLAN vessels, was heading towards the coast of Malaysia. The West Capella, a contracted oil drilling ship, was operating for a Malaysian oil firm in the Malaysian EEZ due south of the Spratly Islands. The U.S. Navy tasked the USS America to maintain a presence and ensure that operations by all parties were peaceful and in keeping with international law while the USS Theodore Roosevelt was sidelined. There were no clashes, but it was obvious that the Chinese presence was precipitated by the operation of the West Capella within the nine-dash line. Beijing had a message to send to all who want to scour their claimed waters. Why else would these ships need an escort from their PLAN partners? In the end, the West Capella was able to do its job while U.S. Navy ships and one Australian destroyer provided a protective blockade to forbid interlopers that loomed in the distance any chance at strong-arming the competition, all without much excitement.

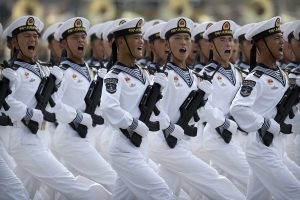

While the Chinese Coast Guard was trying to flex its operating range by going to the southeastern-most corner of the nine-dash line, the Liaoning was conducting sea trials in the South China Sea as well as off of the east coast of Taiwan. The carrier was escorted by two guided missile destroyers and two guided missile frigates. The Liaoning participated in multiple military drills, although it seems to be in the infancy phase in comparison to the rest of their naval war-fighting force. Carrier operations are still a developing facet of Chinese naval war fighting capability. This did not stop them from getting into close proximity with multiple US naval vessels, all while conducting flight operations. Though nothing occurred that would have indicated directly hostile intent toward U.S. forces, they were making sure we knew they were there, and signalling that our presence would not mean they would halt their training in the area.

The timing — the PLAN deployed a “big deck” carrier to the South China Sea just when the news hit about the USS Theodore Roosevelt being sidelined in Guam to deal with the COVID-19 outbreak onboard — was no coincidence. The messaging was obvious. As of this week the USS Theodore Roosevelt is back out to sea to continue its deployment cycle and with this, a leveled Chinese naval response would be expected. With new Chinese carriers on the horizon to be commissioned in the next decade, robust Chinese carrier strike groups — as seen this spring — would not be an uncommon occurrence in the near future. Intercepts from Chinese J-15s, the naval variant of their knock-off Su-27 Russian fighter, will start to become routine. This capability extends their fighter ranges significantly farther than aircraft currently conducting intercepts of Western aircraft, which predominantly come from Hainan Island and the Paracel Islands. Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) flights are likely to be intercepted in uncommon areas as the Chinese carrier deployments become the new normal.

Back in Beijing, the Chinese State Council announced the establishment of two districts within Sansha City under the purview of Hainan province — a bold geopolitical action. The jurisdiction of these two districts in the South China Sea has significant political implications with China’s ability to consolidate its hold in this region this year. Most of the nine-dash line territories are included in this announcement, such as the Paracel and Spratly Islands as well as Scarborough Shoal and Macclesfield Bank . The two districts are broken down into the two main island groups.: Xisha district, headquartered in the Paracel Islands and Nansha district headquartered to the south in the Spratly islands.

The announcement of these districts has been dismissed by some as a symbolic gesture with no real-world consequence. However, this is likely to mean continued infrastructure growth of civilian facilities such as resorts, schools, and housing. By making the Xisha and Nansha districts hot-spots for Chinese tourism, Beijing is likely to complicate the Western effort to enforcing freedom of navigation. It can also be assessed that strategic areas such as Macclesfield Bank and Scarborough Shoal could be developed in similar ways to the Paracel and Spratly Islands in the past decade.

The bar is set on expectations with Chinese aggression in the South China Sea for the rest of the year. While the world fixes its gaze elsewhere, Beijing will continue tightening its grasp. For the immediate outlook, it is likely that the late summer exercise Red Sword will involve aspects of carrier operations linked with the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF). This will directly correlate with aspects of maintaining sovereignty in the South China Sea. At the very least it will involve increased naval integration, fifth-generation fighters, and strategic bombers from mainland China. With the U.S. naval fleet getting back on its feet in the Pacific after COVID-19, this summer will prove to be an important season for U.S.-China relations.

Zachary Williams is an officer in the U.S. Marine Corps. He is also an MBA Student at the University of Maryland Global Campus. Follow him on LinkedIn. The views expressed here are his own and do not represent the views of the U.S. Marine Corps or the U.S. government.