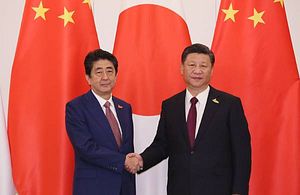

The relationship between the United States and China keeps deteriorating over various issues, from the U.S.-China trade war to the COVID-19 pandemic to the new Hong Kong national security law. At the same time, however, the Sino-Japan bilateral relationship seems to be getting better. Japan’s Shinzo Abe made an official visit to China in 2019, the first by a Japanese prime minister in seven years. During the visit, Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Abe agreed to accelerate cooperation between China and Japan for a “new era.” This agreement was reflected most recently in the recent positive actions of both sides to work together to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. China and Japan have shown their willingness to stick with the promise to develop a “new era” for the bilateral relationship by finding areas for cooperation, not conflict, during the global pandemic.

Japan initiated this effort by sending masks and protective gear, sometimes along with a historical poem in Chinese, originally sent to Jianzhen, a venerable Chinese monk in the Tang Dynasty, by a Japanese prince about 1,300 years ago. Many Chinese citizens took to social media to praise the actions of the Japanese side. According to the Chinese embassy in Japan, Japanese entities and individuals combined had sent 380,000 pairs of gloves, 150,000 protective suits, 75,000 protective goggles, thermometers, and antiseptic solutions to China by February 7. Meanwhile, Japan did not immediately close up its borders to China even after the sizable numbers of coronavirus cases reported in Wuhan — partly in an attempt to salvage Xi’s first official Japan vist, initially scheduled for early April. Japan’s efforts reached an unprecedented level when Japan’s ruling conservative party, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), decided to deduct about $45 from the March salary of most LDP parliamentarians to donate to China.

In return, Chinese central and local governments and the public have donated a significant amount of medical supplies to Japan since March. And according to a source who spoke to the Fuji News Network, the Chinese government reportedly asked its state-run media sources to refrain from criticizing Abe after he claimed that COVID-19 had spread from China. The Global Times, a state-run English-language Chinese newspaper, later expressed its understanding of Abe’s statement, referring to the U.S.-Japan relationship.

Some critics have said that Japan took a step back from the “new era” of Sino-Japan relations by funding its manufacturing factories to “move out of China.” However, these critics seem to be misled, mainly by English language media sources. The Japanese government did commit $2.2 billion to help domestic companies move their supply chains. However, the government’s application guidelines reveal that its primary goal is to diversify supply chains that are too concentrated in any single country, not necessarily only China. The government document does not make any mention that this stimulus package is only for companies that own factories in China.

Japan’s efforts for a “new era” with China also continues outside of the COVID-19 pandemic sphere. Despite the many criticisms, mainly from the West, against the National People’s Congress decision on a new national security law for Hong Kong, Japan has merely expressed its worries rather than directly denouncing the move. Toshihiro Nikai, the secretary-general of LDP, said it is not appropriate to comment on other state’s political affairs.

Japan’s efforts seem to be paying off at the grassroots levels. The Chinese public has become more friendly toward Japan over the past eight years, partially because of Japan’s soft power. The Japan-China Joint Opinion Survey, conducted annually since 2005 by the Genron NPO, shows that 45.9 percent of the Chinese public had favorable impressions of Japan in 2019. That marked a record high since the survey started in 2005, and an improvement of 40 percentage points compared to the same poll in 2013. According to a survey conducted by the Japan Inbound Media Consortium in April, 44 percent of Chinese respondents answered that they want to travel to Japan after the coronavirus pandemic comes to an end, making it the most chosen destination.

Both governments and the Chinese citizens seem to be up for the “new era,” but the two governments must get the Japanese citizens on the same page to achieve success. Despite the dramatic change in the Chinese public’s view of Japan, the Japanese public’s image of China has not improved as much. The Japan-China Joint Opinion Survey shows that only 15 percent of the respondents have a favorable impression of China. This result may be partly due to China’s long struggle to enhance its soft power.

The Japanese public’s view of China is a key to the new era of the bilateral relationship. Future backsliding could come up from the public rather than the government. Also, it matters because Japanese decision-makers have to take public opinion into consideration for their democratic elections. Therefore, China should seek to improve its image among Japanese citizens by effectively increasing its soft power. If China fails to do so, it may hamstring Japanese decision-makers’ efforts to keep positive momentum for the “new era.”

If the Japanese government really wishes to improve ties, it also needs to work to help China better the Japanese public’s impressions of China by promoting more positive aspects of recent actions from China, accepting more Chinese cultural institutions such as Confucius Institutes, and expanding educational exchanges. This would make the Japanese citizens more open to China’s soft power, resulting in a better impression of China.

Kazuki Nakamura is a member of the Young Leaders Program at Pacific Forum. He has previously assisted with research at New York University and UNCTED.