Maria Ressa, executive editor of the news website Rappler, and former Rappler reporter Reynaldo Santos Jr. were found guilty of “cyber libel” by a Philippine court on Monday in a case watchdogs called a blow to media freedom with the potential to reverberate throughout local and digital newsrooms.

Ressa and Santos were sentenced to a minimum of six months and one day and a maximum of six years in prison and ordered to pay $8,000 in damages to Wilfredo Keng, the businessman who lodged the complaint in 2017. They will be allowed to post bail, pending an appeal.

Since Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte came to power in 2016, at least eight cases have been filed against Ressa and Rappler, which has reported critically on the government’s deadly drug war. Monday’s verdict is a result of one of those cases.

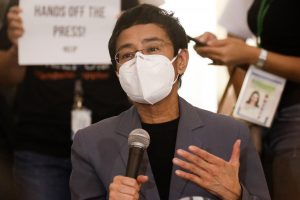

Ressa told reporters after the verdict she would continue to fight the case and urged Filipino journalists to “protect your rights.”

“We are meant to be a cautionary tale,” she said. “We are meant to make you afraid. But don’t be afraid. Because if you don’t use your rights, you will lose them.”

The case stemmed from an article published in 2012, months before the passage of the cybercrime law used to prosecute Ressa and Santos, whose name appears on the story’s byline. But prosecutors determined the story to be “republished” in 2014, after it was updated to correct the spelling of one word, allowing it to be subjected to the cybercrime law.

Critics called the charges politically motivated, noting the libel case was not filed until 2017 and comes amid a series of active cases targeting Ressa and Rappler. In the Philippines, libel is a criminal offense.

Duterte has threatened to shut down Rappler, using spurious allegations of foreign ownership, and has banned its reporters from covering the presidential palace.

The verdict comes amid what watchdogs call an ongoing backslide into crackdowns on freedoms of speech and the press, along with an erosion of judicial independence under the Duterte administration.

Last month, the government shut down ABS-CBN, the country’s leading television network, after it had repeatedly drawn Duterte’s ire for its reporting on the drug war and other administration policies.

Duterte is expected to soon sign a broad anti-terrorism law, which could allow online critics of the administration to be arrested without warrant and detained for up to 24 days without charge.

Last week, students, journalists, and activists opposed to the law found “clone accounts” resembling their own on Facebook and, in some cases, reported harassment from these duplicate accounts.

The government has also arrested authors of social media posts critical of the government’s COVID-19 response. Police and government personalities have labeled volunteers and activists as members of the communist New People’s Army (NPA), a practice known locally as “red-tagging” that, in the past, has led to harassment, arrests, and extrajudicial killings.

Monday’s verdict against Ressa could set a precedent for criminal “cyber libel” charges to be brought against Filipino journalists whose reporting offends prominent government officials and businesspeople, raising fears that reporters will temper their coverage to avoid long legal battles they cannot afford and may ultimately lose.

Journalists for small outlets outside of Manila have faced harassment in their communities and online. Monday’s verdict led many to worry their legal defense against their press freedom had suffered yet another seismic blow.

Reporters in local newsrooms may find a worrying example in the story of Alex Adonis, a radio broadcaster in Davao convicted of libel in 2007 and sentenced to four and a half years in prison after he could not afford a lawyer.

Adonis, at the time a commentator for the radio station dxMF Bombo Radyo (or Booming Radio), had reported on a congressman’s alleged love affair. The congressman denied the allegation and, in 2001, filed a libel case against Adonis.

Adonis was reportedly unable to afford legal representation on his salary of about $150 per month and struggled to travel between Cagayan de Oro, where he had been reassigned, and Davao, a seven-hour bus trip away. He eventually left the radio station and his lawyer withdrew from the case, leading him to stop attending his hearings.

Following Monday’s verdict, presidential spokesperson Harry Roque said Duterte “has never been behind any effort to curtail press freedom in the country.”

The decision, however, was condemned by human rights and media freedom groups wary that Duterte has added another weapon to his arsenal in his administration’s crackdown on critical journalism.

“The verdict basically kills freedom of speech and of the press,” the National Union of Journalists in the Philippines said in a statement. “But we will not be cowed. We will continue to stand our ground against all attempts to suppress our freedoms.”