Afghanistan has experienced many years of seclusion and war, most recently under the U.S.- led war that started in 2001. Higher education has been among the areas most impacted, with advanced education’s faculty, framework, and spending plans all drained by the continuous clashes dating back decades. Since the end of the Taliban regime, the sector of higher education in Afghanistan has undergone a remarkable improvement but, despite all the accomplishments made, the nation’s education framework is confronting significant imperfections.

After three months of deferring the Afghan national university entrance exam, Kankor, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the National Examination Administration (NEXA) declared on its Facebook page that the first round of the Kankor test for high school graduates would begin on July 16. Usually, the Kankor exam is held in the winter every year; it was delayed this time because of COVID-19.

I have been doing analytical research based on Kankor’s records of 2 million students for 18 years. My research found that there is a vast ethnic and regional disparity in student enrollments in Afghanistan’s universities.

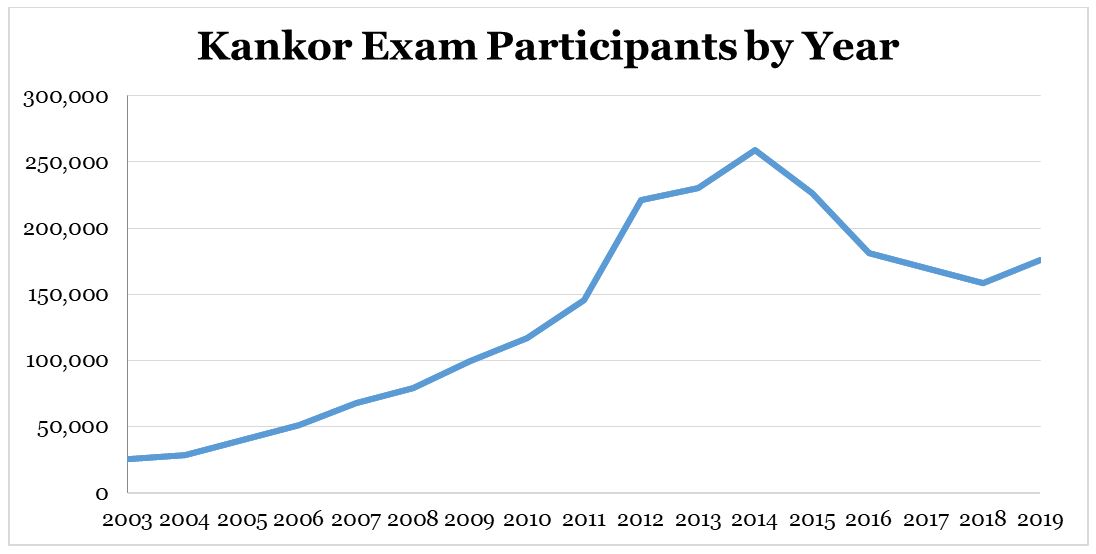

My analysis of the 2 million Kankor records shows that the number of participants in the exam has increased noticeably in the last few years. In 2003, around 25,000 students took part in the Kankor exam, but that the number of participants has increased substantially in more recent years. The number of high school graduates taking the test ballooned in 2014, reaching a high point of 259,000 (see Figure 1).

After a sharp decline in students’ participation post-2014 (the same year U.S. troops began withdrawing from Afghanistan), Kankor participation is signaling a revival of enthusiasm toward universities among young Afghans. Professor Abdul Qader Khamosh, the head of NEXA, recently told the press that this year around 210,000 high school graduates will take part in the Kankor exam.

Figure 1: The total number of national Kankor participants by year. Data from the author’s own compliation of the Kankor dataset.

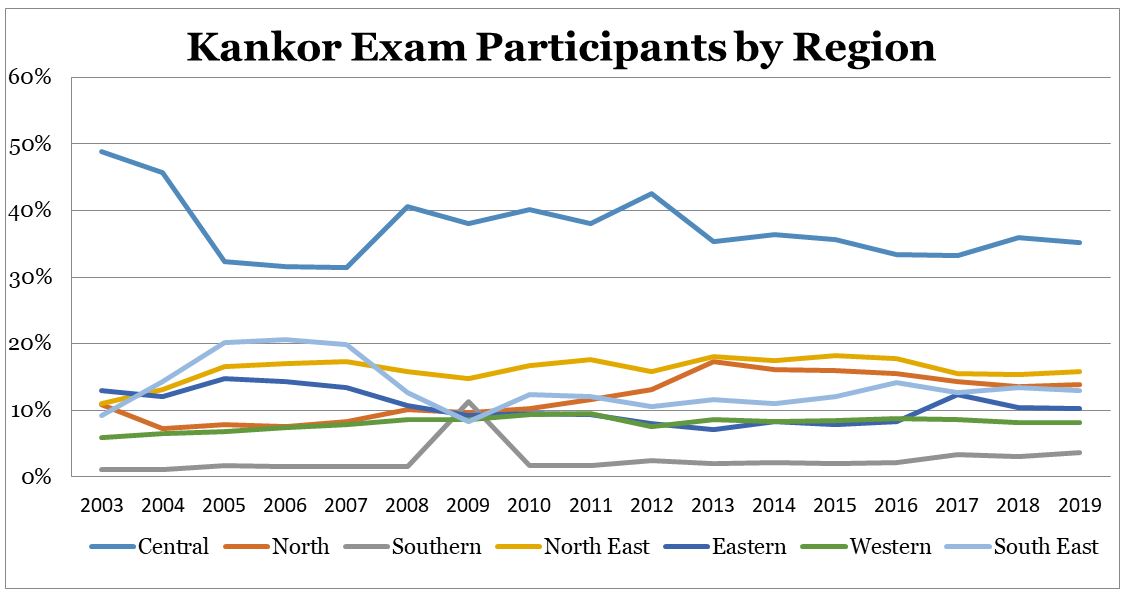

Participation rates in the Kankor exam reveal something important about students’ access to higher education. In terms of student participation in the exam – and, by proxy, enrollment in higher education — the Kankor data unveils a huge ethnic and regional gap.

In 2018, Badakhshan, a northern province in Afghanistan with a population of around 1.03 million people, had 8,616 students sit for the Kankor exam. In contrast, Helmand, a southern province in the country with a population of around 1.42 million, had just 1,868 students participate in the Kankor test. Likewise, Kandahar province in the south (population 1.36 million) and Takhar province in the northeast (population 1.073 million) had a total of 3,479 and 7,773 participants, respectively. There are many other comparative examples indicating that the Kankor participation of high school graduates in some provinces lags noticeably behind.

My analysis of the Kankor records based on the seven zones of the country that NEXA recently created for the regional quota system also indicates a considerable gap in total participation from each zone. Figure 2 shows the percentage of high school graduates in the Kankor exam from the seven zones of the country, with the central region by far the best represented. The data shows the stark regional inequality in terms of students’ participation in the exam, and thereby in higher education. This leaves a lot of students deprived of higher education, and the provinces bereft of qualified human resources.

Figure 2: The percentage share of Kankor participants in seven different regions across the country. Data from the author’s own compilation of the Kankor dataset.

In 2018, authorities from the Ministry of Higher Education, NEXA, and the government worked out a mechanism to attempt to provide equal opportunities for the students of underdeveloped provinces by reserving a 25 percent share of seats in the top 14 universities for indigenous citizens across the country. The plan, which was presented and later approved at a cabinet meeting, was put in place in 2018. However, this plan was criticized by some for monopolizing the higher education system and is deemed as prejudicial toward certain ethnic groups. In general, Pashtuns are more concentrated in Afghanistan’s south, and that ethnic group has long been accused of outsized dominance over the central government. But NEXA refuted this charge, emphasizing that the regional quota system was not developed based on the demography of the provinces.

The regional-based quota system for higher education, which was put in place to balance the participation of students from undeveloped and underprivileged provinces in the education sector, included all the provinces of Afghanistan except Kabul. However, the quota for each province is not exactly clear, nor is the basis on which the plan allots the each province’s proportion.

Although the higher education sector in Afghanistan has come a long way and there has been significant progress, the fact of the matter is that some regions of the country are still lagging significantly behind when it comes to the proportion of student participation in the Kankor test and their enrollment in the higher education.

Laiq Zirack is an assistant professor in the faculty of public administration and policy at Kandahar University as well as the director of the Pacha Khan Center for Peace and Non-violence Studies, Kandahar University.