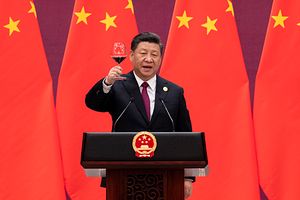

The European Union (EU) is not a centralized state by nature, while in China the decision-making power has been centralized under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). However, Beijing’s foreign policy and the practices of its diplomats seem to more and more reflect the conceptions not of one party, but of one person: Xi Jinping. This became even more explicit when China’s Foreign Ministry established a research center studying Xi’s thoughts on diplomacy on July 20. The recent COVID-19 pandemic, the Hong Kong National Security Law, and the activities in the South China Sea gave Europe and other regions a chance to observe Xi’s way of conduct, coated with the growing assertiveness of China on the world stage. Faced with an extremely centralized counterpart like Beijing, Brussels and member state capitals have no choice but to unite themselves when articulating and implementing the EU’s grand strategy vis-à-vis China.

The EU and many of its member states had a bitter experience with China’s foreign policy and diplomatic practices during the COVID-19 crisis, when the EU’s diplomatic chief Josep Borrell stated the existence of a “battle of narratives.” Analysts in Europe have also raised awareness that China’s approach toward the EU is not unique to the pandemic but rather a long-term strategy to consolidate its power and compete for control of the international system.

The term “wolf warrior” turned into a buzzword during the pandemic as Beijing’s Foreign Ministry spokespersons and diplomats in EU countries and around the world became much more assertive than ever before. Sources from inside China’s Foreign Ministry revealed that Beijing’s foreign policy and practices during the public health crisis can, in fact, be traced to Xi’s instructions to Foreign Minister Wang Yi and the ministry at the end of 2019. Xi expects China’s foreign service officers to gear up their fighting spirits. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, back in September 2014, Xi had already called upon China’s “United Front Work” apparatus – both party and state bodies – to enhance their effectiveness in foreign influence.

Although not covered much by the media in Europe and North America, the “Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy Research Center” was established on July 20 in Beijing. The center, as reported by the state news agency, Xinhua, was founded by the Foreign Ministry and supported by the China Institute of International Studies.

In his speech at the inauguration ceremony of the center, Wang Yi stated that Beijing’s diplomacy has been led by the CCP and guided by Xi’s thought. The result is that China has overcome difficulties and achieved historical success in recent years. (The full text of this speech, entitled “Deepening the study and earnest implementation of the Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy to break new ground for the major country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics,” has not yet been published in English on the ministry’s official website.) Wang reminded the staff of his ministry to profoundly study Xi Jinping Thought and devote their energy to creating the new era of major country diplomacy with Chinese characteristics.

The new center was an explicit gesture of Beijing’s move from centralizing foreign policy and external relations in the hands of the CCP to those of Xi alone. What is more, diplomats’ practices at home and abroad can be interpreted to reflect the expectation and authorization of Xi himself in the future. Beijing is not only delivering this message abroad but also to its party-state system internally: A Xi-centralized era of China’s diplomacy has arrived.

In this context, the coronavirus crisis may be understood as a window of opportunity for Beijing to test the preparedness of both its foreign policy and diplomatic practices under the guidance of Xi’s spirit. The EU’s open and democratic model was challenged but was not struck down by this wave. However, it should be the impetus for the leaders in Brussels and national capitals to move away from an inaccurate, even naïve, assessment of Beijing.

Not being a centralized state by nature, the EU is already at a comparative disadvantage in policymaking and strategic planning when facing China, a state actor that is extremely centralized in this sense. Even though this is always easier said than done, and is becoming a cliché, the first priority – if not the bare minimum – for the EU is surely to unite its position on China.

On July 21, after the first European Council meeting in person, the heads of state or government of the 27 member states and the chiefs of EU institutions demonstrated their dedication and capacity to face and solve problems together regarding the severely COVID-struck European economies. Aside from the financial and economic aspects, it may be interpreted as a firm political message that the 27 member states can coordinate an agreed-upon solution for one union together, even though it requires titanic efforts and tireless negotiations.

This kind of will and skill is required for the EU to face China, which has been showing increasing assertiveness under the Xi-centralized era of foreign policy and diplomatic practices. Brussels and national capitals definitely need to identify their unified priorities on both the ends to achieve and the means to adopt in relations with Beijing in order to be a competitive counterpart. This is what scholars, think tankers, and practitioners call a “grand strategy.”

The next physical EU-China summit has yet to have a date. Looking ahead, there are still several disputed but very critical issues that the EU needs to unite its positions on before negotiating with China. 5G, Iran, Syria, North Korea, the South China Sea, connectivity and infrastructure, a COVID-19 inquiry, climate and environmental issues, the Hong Kong National Security Law, human right violations in Xinjiang, the meaningful participation of Taiwan in the international arena, and negotiations on the EU-PRC Comprehensive Agreement on Investment may all be on the list of possible topics.

It is pragmatic that the EU approach China as a different type of counterpart based on the issues concerned. Moreover, the EU may not always share identical positions and perceptions as the United States toward China, since the union has its own interests to pursue and its values to safeguard. What is vital is that the EU needs a unified stance and a common approach to articulating and implementing its grand strategy with regards to China.

Earl Wang is a doctoral researcher and lecturer in political science at the Centre for International Studies (CERI) – Sciences Po.