Last weekend Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi became the first foreign dignitary to embark on an official visit to Cambodia amid the COVID-19 pandemic. His visit to Cambodia, part of a four-country tour, is more than just a normal regional trip undertaken to bolster bilateral diplomatic ties and to reflect solidarity in difficult times. Instead, some contentious regional issues — including the Japan-promoted Free and Open Indo-Pacific concept as well as tensions in the South China Sea — dominated the agenda of Motegi’s visit.

His trip demonstrated that Japan is taking another step further to expand its engagement with Cambodia, one of the most prominent of China’s allies in the region. Besides Cambodia, Motegi’s trip included stops in Laos and Myanmar— countries where Chinese influence also ostensibly has deep roots.

What has prompted Japan to swiftly act now to expand its regional role? Clearly, the growing Chinese aggression in territorial claims in both the East and the South China Seas. In its annual defense review released last month, the Japanese government under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe explicitly raised concern over China’s rapid military modernization as well as directly disparaged China’s relentless unilateral expansion of its territorial claims in both the East and South China Seas while other countries have been locked in a battle against the pandemic.

It should be noticed that the Japanese foreign minister’s regional visit also came just a few weeks after the Japanese government inked a deal to provide Vietnam, another South China Sea claimant, with six patrol ships that will boost Vietnamese military capability. Japan said the deal will contribute to the realization of a free and open Indo-Pacific.

It’s not only Chinese aggression that matters to Japan at the moment. China’s snowballing sway in assisting other countries with the pandemic also poses a stark concern for Japan. From mask to vaccine diplomacy, Beijing has been deploying all possible tools. In case Beijing does successfully develop a COVID-19 vaccine — something China’s leadership calls “a public good” that will be shared with the rest of the world — Tokyo would find it even more strategically challenging to compete with China. If Japan doesn’t quickly act, it may be far from leading the race.

Countering Chinese Influence in Cambodia

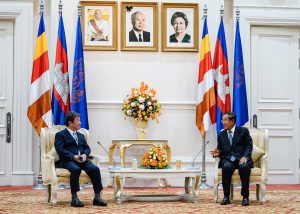

While in Cambodia, Motegi clearly explained to his Cambodian counterpart, Prak Sokhonn, that it has become more important than ever for the Free and Open Indo-Pacific concept to be further reinforced as the international landscape has been considerably shifting as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduced by Abe in 2016, the strategy aims to promote closer cooperation and trade between countries in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East while accentuating the importance of a rule-based international system including freedom of navigation as well as ensuring peace and stability in the region.

Meanwhile, during his courtesy call on Prime Minister Hun Sen, in order to strengthen the Indo-Pacific strategy, Motegi highlighted the Japanese government will continue to support infrastructure projects in Cambodia. That includes the development of Cambodia’s sole deep-water port in Sihanoukville — the province where Chinese investment has been prevalent, from investing in casinos to building hotels and restaurants. The port modernization project is funded by a Japanese government loan of $209 million. Once completed in early 2023, the port is anticipated to be a key trading gateway that strategically boosts Cambodia’s growth.

As of June, however, China remains the largest investor in Sihanoukville. Chinese companies account for a majority of the province’s 194 investment projects under construction between 1994 and 2020, worth a total of $30 billion.

In addition to being the leading investor, China also has been alleged to have established a naval base in the province — a claim that the Cambodian government has repeatedly denied and branded as “a fabrication.”

By asserting the importance of energizing the Indo-Pacific framework, Japan is trying to fortify its position in countering China’s rising influence in Cambodia in particular and in the region in general. And with this in mind, it is critical that Japan do more to support and work with any country that regard its role in the region as vital, as well as any country where Chinese clout is ominously mounting.

There is no doubt that Japan still views Cambodia as an important regional partner. Accordingly, ensuring that Cambodia won’t continue falling further into China’s orbit is one of Tokyo’s principal goals. But Japan supporting the above-mentioned projects might not be enough to contest China in Cambodia. Japan must also do more in expanding investments in Sihanoukville province to keep Chinese influence in check.

As Japan’s strategic partner, Cambodia has so far expressed interest and embraced the Japan-spearheaded Indo-Pacific concept. Phnom Penh believes that the strategy primarily pursues economic prosperity through closer engagement rather than pushing countries involved to take sides — which would risk violating neutrality and undermining inclusive regional cooperation.

As can be seen, in the meantime Cambodia has tried to manifest its determination to promote the ASEAN Indo-Pacific outlook which keeps ASEAN at the center of regional cooperation with ASEAN centrality, the rule-based system, and the principle of non-interference being underscored.

Enhancing Bilateral Defense Ties

With China in mind, Japan will continue to deepen not only diplomatic and economic ties but also defense cooperation with the Southeast Asian region, including Cambodia.

In late June, Japan’s Ministry of Defense announced that it would establish a new post in charge of any affairs in ASEAN as well as the Pacific islands. That signals that upgraded military cooperation with ASEAN countries, including Cambodia, can be expected through several mechanisms including military aid, technical training, as well as military equipment exports.

The Cambodian government is, on the other hand, likely ready to accommodate Japan’s growing military engagement. It should be recalled that Hun Sen himself, during a meeting in February with General Goro Yuasa, chief of staff of Japan’s Ground Self-Defense Force, voiced his interest in seeing increased military cooperation with Japan in the areas of information exchange, counterterrorism, and training. Hun Sen also encouraged the Japanese side to provide more military assistance for the country in demining and emergency response.

However, it remains to be seen how far Japan’s overall military cooperation with ASEAN countries can go as it rests upon the country’s evolving defense policy, which has been confined by a pacifist constitution and other legal limitations. However, Japan perceiving China as a long-term threat will likely push it to take further steps in dealing with the conundrum in its post-war constitution.

Cambodia Needs Japan’s Expanding Role

Motegi’s visit to Cambodia also comes nine days after Cambodia effectively lost 20 percent of its preferential trade treatment under the “Everything But Arms” (EBA) scheme granted by the European Union due to its poor human rights records.

Even though the visit is not primarily connected to recent developments in Cambodia’s domestic affair, it still exhibits that Japan is prepared to do more to engage and assist Cambodia during this difficult time.

Cambodia now apparently needs Japan’s support more than ever due to the fact that its relations with the West — especially the EU and the United States — remain at an all-time low, entailing a long time and genuine effort to reset.

With the EBA trading preferences partially withdrawn, Cambodia anticipates the closure of several factories, leaving several thousand workers out of employment.

Even worse, the country’s economy has already suffered a dire blow due to the pandemic. According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Cambodia’s economy is projected to shrink by up to 5.5 percent this year, which could possibly cost between 150,000 to 200,000 workers their jobs.

Cambodia’s future really looks grim. The economic fallout has already driven the country to desperate action in trying to diversify its economy as well as exports.

The Southeast Asian country can, of course, look into Japan’s initiatives, be they multilateral cooperation mechanisms like the Free and Open Indo-Pacific or Japanese initiatives on overseas loans and investments — all of which can offer profound funding in infrastructure advancement and stabilizing economic development in the post-pandemic times.

Moreover, Phnom Penh also appreciates Tokyo’s soft position and constructive engagement. When it comes to fostering ties with Cambodia, it is unquestionable that Japan has always had more leverage compared to China. Japan’s soft power is predominant among Cambodians, enjoying an unmatchable and well-respected reputation.

And Japan remains Cambodia’s largest traditional donor. Tokyo provided more than $2.8 billion in official development assistance to Cambodia, nearly 15 percent of financing from all development partners from 1992 to 2018.

Traditionally, Japan also apparently has more sway over Cambodia in many aspects, even in political matters (despite the fact that Tokyo has been criticized for its silence on the political clampdown and human rights issues in Cambodia). Japan, on the other hand, has persistently backed the process of decentralization and political reforms in Cambodia.

A striking feature is Motegi’s message prior to his visit, in which he reaffirmed Japan’s continuous support for Cambodia’s democratic development with its own characteristics — a concept that appears in contrast with Western countries’ approach to democracy promotion.

Japan’s position in dealing with Cambodia can’t be automatically interpreted as cozying up to Cambodia’s human rights and democracy backtracking. The Japanese approach has customarily been driven by geopolitical factors, and of course Tokyo can also comprehend how such sensitive issues should be handled in sensibly effective and proper ways.

Sao Phal Niseiy is a Cambodian journalist who has a deep interest in foreign affairs.