Japan’s worsening depopulation crisis is crippling the public finances of regional towns. Now one small town has made national headlines after expressing interest in storing radioactive nuclear waste underground in a last ditch effort to save itself from impending bankruptcy.

The small town of Suttsu in Hokkaido, the northernmost main island of Japan, has a population of just under 3,000 people. It’s the first local municipality to volunteer for the permanent storage site of highly radioactive nuclear waste and nuclear spent fuel. Suttsu Mayor Kataoka Haruo says the town has no more than 10 years left to find new sources of income after struggling with a slump in sales of seafood due to the global coronavirus pandemic.

Kataoka says there is an impending sense of crisis unless an urgent financial boost in the form of a government grant can be secured. He has called on local residents not to dismiss the idea of applying for the phase one “literature survey” without weighing the ways the grant could be spent — in contrast to the harsh reality of town funds running dry in 10 years’ time.

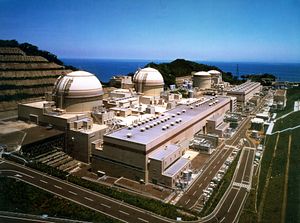

In Japan there are more than 2,500 containers of nuclear waste being stored in limbo without a permanent disposal site. Currently, the waste is stored temporarily in Aomori prefecture in northwest Japan at the Japan Nuclear Waste Storage Management Center. According to the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry there are also approximately 19,000 tons of spent nuclear fuel stored at each nuclear power plant.

Nuclear waste projects immense heat and it needs to be cooled through exposure to air for between 30 to 50 years before it can be transferred and stored underground. However, it takes roughly 1,000 years to 100,000 years for radiation intensity to drop to safe levels.

The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster left long-lasting trauma further exasperating Japan’s already vexed relationship with nuclear energy as a resource deficient nation. The aftermath of the disaster and the slow road to recovery prompted many people to object to nuclear waste storage not only on geographic grounds but also out of strong emotional opposition.

Hokkaido has built a global reputation for its high quality dairy, agricultural products, and seafood. Nuclear waste storage, and the negative publicity that would follow, could jeopardize those industries.

With the proposal, local residents in Sutsu have been placed in a difficult situation, weighing up the health of their children and future generations against the town’s financial prospects and viable funding opportunities.

In August, Kataoka said he would not apply for phase one without the understanding of the general public. Last week, Kataoka held a local briefing session aiming to deepen local understanding and consent. But after discussing the damage to the town’s reputation and the possible conflict with a previous ordinance against accepting nuclear waste set by a radioactive waste research facility created in Hokkaido in 2000, Kataoka indicated the application for phase one would likely be delayed.

In 2000 the government enacted the Final Disposal Law, which outlined criteria for electing a permanent storage site. A three-stage investigation process sets out excavation to be deeper than 300 meters below ground and in doing so a survey of volcanoes, active fault lines, and underground rock must be performed in addition to installing an underground survey facility. It’s estimated that steps one through to three will take approximately 20 years in total.

In 2017 the government released a scientific map of Japan, pinpointing towns with suitable geographic conditions to host final disposal sites. If the application and survey are approved successfully, towns are eligible for grants up to 2 billion yen (around $19 million at current exchange rates) from the central government and another 7 billion yen if stage two goes ahead. In 2002 The Nuclear Waste Management of Japan (NUMO) launched an open call for local municipalities to consider applying for an initial investigation stage without success. Three years after the release of the map, NUMO has attempted to garner public support by hosting over 100 local discussion meetings all over Japan. Suttsu was the first town to express interest in phase one out of 900 local municipalities.

The final nuclear waste site is expected to make room underground for 40,000 barrels requiring six to 10 square kilometers — the equivalent of 214 Tokyo Dome Stadiums — to a tune of 3.9 trillion yen.

The government is currently formulating a “nuclear fuel cycle policy,” which aims to reduce the amount of nuclear waste generated by encouraging the recycling and reuse of spent fuel. But one major criticism of Japan’s nuclear power policy is the lack of a comprehensive strategy. The two year period for a “literature survey” has been touted as an opportunity for Japan to seriously consider the cleanup of nuclear power.