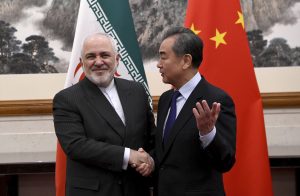

On October 10, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi proposed the formation of a forum in the Middle East to foster multilateral engagements with “equal participation of all stakeholders.” The forum seeks to “enhance mutual understanding through dialogue and explore political and diplomatic solutions to security issues in the Middle East.” At the same time, states would have to express their support for the 2015 Iranian nuclear deal as a “precondition” to get membership in the forum.

Iran has been involved in a web of rancorous political dynamics as part of its rivalry with Saudi Arabia, as seen in Tehran’s support to the Houthis in Yemen, its objective to maintain influence over Iraq’s politics, and its proxies active in Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine. Iran’s tensions with Israel have also largely been responsible for the latter’s increasing engagement with the Arab states in recent times. Relations between Iran and Turkey also seem to be teetering as a result of layers of divergences (the Syrian conflict and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict) laid over their limited convergences of interests (questioning the status quo in Middle Eastern order).

Against such an unstable backdrop, it is questionable whether the states in the Middle East will come forward to participate in the China-led forum by backing the nuclear deal. There seem to be only lean prospects of even neutral states like Oman getting on board right now. With a very low probability of the forum acting as a platform to accommodate diverse views or act as a mediating framework, this initiative might well reach a dead end.

Having said that, the proposal is indicative of China’s deepening interest in conflict management in the Middle East. As the definition goes, conflict resolution generally seeks to resolve incompatibilities of interests and behaviors that drive conflict by recognizing and addressing the underlying issue. Conflict management, by contrast, is very much restricted to those actions that prevent further escalation of the conflict by controlling its intensity through negotiations and interventions, among other mechanisms.

China seems to be playing the peace-broker card out of its broader Middle Eastern security imperatives. First, and most prominently, China, as the largest importer of oil from the region, has to ensure that its energy security remains unhindered. Second, as the rift between the United States and China grows, the Middle East presents itself as an attractive ground for China to challenge the U.S. position with its economic might and its subtly penetrating political involvement. Finally, sudden spurts in tensions near the Strait of Hormuz and the Persian Gulf have alarmed China into tightening the security of its stakes in the Middle East. This concern has become more salient after the roll out of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013. Therefore, it is important for China to ensure some degree of stability in a region that been constantly vulnerable to conflicts.

Unlike the United States, and like Russia, China has managed to maintain a working relationship with the major powers of the region – Iran, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey alike – as well as the middle powers and weak states. China, with the help of Russia, has effectively resisted the United States’ push for U.N. sanctions on Iran. More significantly, it has bought the silence of these Middle Eastern states on issues related to its treatment of Uyghurs and on the Hong Kong issue. However, to what level can China afford to extend itself to cater to the wish lists of these states?

The United States still prevails as the most powerful extra-regional actor in the Middle East, with a strong alliance system that has Israel and Saudi Arabia as its two pillars. Washington’s reach and persuasiveness were demonstrated through its ability to mobilize support for Israel’s normalization of relations with some of the major Arab states. The superpower has so far been very much successful in winning the support of the regional powers to take actions against Iran, but that seems to have been hindered by the lack of endorsement from Europe. Nevertheless, this cannot totally shake the United States’ position in the Middle East.

For China, however, mediation diplomacy can help cultivate a public image of its intentions to broker peace in the Middle East. Such gestures can possibly fetch Beijing a conducive environment to widen its sphere of influence to make sure its core interests and security are not at risk.

While Iran and some other Middle Eastern states seem to be looking up to China to play a stabilizing force that can resolve conflicts in the region, Beijing has restricted its focus to conflict management measures such as conducting negotiations, offering mediation, and providing economic support and other prudent diplomatic maneuvers. China’s mediation efforts have long stuck to its so-called principle of non-intervention in the internal affairs of these states. At the same time, alongside its rise in the world order, China has been channeling resources toward managing conflicts in the Middle East, as part of its grand mission to project itself as a responsible great power.

Over the years China’s footprints in the Middle East has proliferated, and it has gone from leaving the burden of conflict management to the other extra-regional powers in the region to playing a notable role in some of the peace efforts. This includes its role in management of the Syrian and Yemeni crises and of the Sudanese negotiation process in the larger Middle East and North Africa region. Irrespective of whether practical results were yielded or not, the Asian giant’s actions have been suggesting its aspirations in the Middle East, in consonance with its interests and capability. It is titled more toward conflict management, enough to secure its stakes and dividends, instead of dipping its feet into the puddle of military and political interventions. China’s approaches thus seem to be more focused on solutions that can contain tensions and bring about negative peace rather than long-term, futuristic, and sustainable solutions.

Beijing’s current approach does not signal its interests in getting involved in the conflict resolution initiatives but remains restricted to conflict management. The Middle East multilateral dialogue forum, if it is ever fully instituted, might stick to these limited goals of managing conflicts as long as China’s core economic and energy interests are served.

Poornima Balasubramanian is a Dr TMA Pai Fellow and Doctoral candidate at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India. Her research interests include Geopolitics of MENA, India- MENA relations, International Negotiation, Peace & Conflict studies. Follow her on Twitter: @aminroopb.