Pakistan’s 11-party opposition alliance, the Pakistan Democratic Alliance or PDM, staged its second show of strength in the country’s commercial capital, Karachi, on October 18.

To the chagrin of the government and the country’s powerful military, speaker after speaker at that rally voiced vehement support for upholding the cause of civilian supremacy in a democracy, thereby shifting the debate toward a discussion around the military’s interference in politics and civilian affairs.

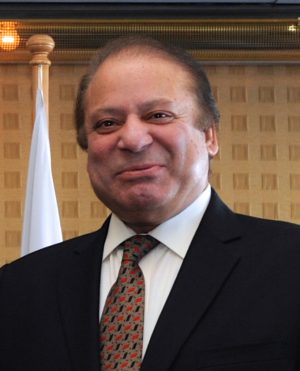

All estimates suggest the Karachi show was more impressive than the one staged two days before in Gujranwala, when former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s speech created waves across Pakistan. Sharif did not mince his words while naming the country’s army chief as being behind rigging the July 2018 elections that brought Imran Khan to power.

All television news channel in Pakistan switched to studio talks, ads, and recorded analysis — and away from live scenes of the opposition’s October 16 gathering — as Sharif appeared on the screen to address his party’s highly charged activists via video link from his London home.

Days before, the Pakistan Media Regulatory Authority had issued an order baring all TV channels from broadcasting speeches and interviews of “absconders.” According to Pakistani government, the three-time premier Sharif is among them.

But there is also one other reason, and quite understandable, for keeping Sharif from appearing on the television screens: the Vote Ko Izzat Do or “respect sanctity of the vote” narrative.

Whenever it comes to the vote’s sanctity or that of the constitution and parliament, the proverbial accusing finger automatically moves in the direction of Pakistan powerful army. It is because the military directly ruled Pakistan for more than half of its 73 year history. This does not include what politicians call “indirect interference” in civilian affairs from behind the scenes.

Notwithstanding Sharif’s personal ambitions (that some commentators call follies), his three terms in office — two in the 1990s and the third from 2013 till 2017 — all ended prematurely while struggling for civilian supremacy. However, it was his third term that turned this once “establishment’s man” into an icon of the anti-establishment struggle.

One worrying factor in Sharif’s Vote Ko Izzat Do narrative — from the establishment’s point of view — is his praise for, and acceptance of, the ethnic Sindhi, Pashtun, and Balochi nationalist leaders who struggled for provincial rights and constitutional supremacy and who were labeled gaddaars (traitors), “anti-state,” and “foreign agents” in the past. “The real gaddaars are the ones who violated the constitution,” said a visibly angry Sharif in an unambiguous gesture to the military generals who toppled elected governments in the past.

However, the real bombshell in Sharif’s candid speech was his direct charges against the Pakistan army chief, General Qamar Javed Bajwa, and chief of the Inter-Services Intelligence, the country’s prime intelligence agency, Faiz Hamid, for rigging the 2018 elections and bringing Khan into power. “Bajwa Sahib! You would have to answer for this,” Sharif demanded.

This is probably the first time in Pakistan’s history that a leading politician from the country’s mainland Punjab, one of the main recruiting zone of the Pakistan armed forces, has challenged a sitting chief of the powerful institution by mentioning his name in a public gathering.

Analysts and commentators refrain from discussing issues like the one Sharif raised openly in the talk shows and use metaphorical language instead. But privately, many believe, there will be consequences both for the Sharif family and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) party that Sharif leads, as well as for the Khan government.

A sedition case had already been registered against Sharif and his key party associates in Lahore, the ex-premier’s hometown and his PML-N’s strong bastion, early this month, but that is far from the end.

The writing on the wall may become visible in the next few days, but a rather expected outcome could be an addition of some more names, this time from the pro-establishment Punjab, to the old and long list of “gaddaars”, “anti-state” and “foreign agents.” Rebellion against Sharif and fragmentation of his party, a time-tested tool in Pakistan’s political minefield, may be another possibility.

But wait a while. Sharif was not the only one who lashed out at the military for its political gimmicks. Other leaders such as Bilawal Bhutto and Raja Pervez Ashraf of the Pakistan People’s Party, Maulana Fazlur Rehman of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi of the PML-N, Mahmood Khan Achakzai of the nationalist Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party, and Dr. Abdul Malik Baloch of the Baloch nationalist National Party also criticized the military interference in civilian affairs. These are political heavyweights.

Although they were not as frank and candid as Nawaz Sharif, their reference to the “selectors” and the “selected” have become part of Pakistan political terminology as the former refers to the military establishment and the latter to Khan. It is the same as the euphemism Khalyee Makhlooq, which refers to the country’s intelligence agencies.

“I tell you Imran Niazi, that you are but a puppet and selected,” exclaimed Bhutto. He added that the opposition alliance would throw a challenge to the “selected” and the “selectors” in its Karachi public meeting on October 18.

Rehman, the key figure behind uniting and persuading the opposition parties for launching the movement against Khan’s government, said the establishment gets annoyed if politicians publicly name them for rigging the elections. “They slaughtered democracy in public and yet expect us not to name them publicly,” he said in an apparent reference to the establishment.

The next few weeks and months are important for Pakistan’s democracy mainly because the opposition parties have played their final card of coming out to the streets to challenge both the government and the military establishment head on. Whether they will succeed is anybody’s guess. Much depends on unity in their ranks and the establishment’s reaction.

The government and its nearly half a dozen spokesperson have launched a counterattack by calling the opposition leadership corrupt officials who looted the country’s wealth and shifted it abroad. But this smear campaign — which worked well in the pre-2018 elections period and for some time even after the formation of the current government — is not going to be effective anymore mainly because the common public is yet to see on ground changes in terms of things that matters to it the most: prices of daily commodities and utilities.

The military, always conscious of its image, seems to be in a dilemma. Continuing with Khan and the “same-page” mantra is costing the military its image because the common man believes the army is propping up a government that is unable to deliver in terms of controlling inflation and providing jobs. However, jettisoning Khan will leave the military with no visible friends as the joint opposition has already become “untrustworthy.”

Narratives, speeches, and power shows aside, it has always been true that the bayonets had the upper hand in previous political unrest in Pakistan. This time might be different.