The recent visit of Yang Jiechi, a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Politburo member and previously China’s foreign minister, to Sri Lanka sparked interest among many. To begin with, Sri Lanka’s opposition raised concerns about the visit of the Chinese delegation amid a global pandemic and the delegation not being subject to usual quarantine practices. These concerns were followed by the widely speculated Chinese debt trap narrative in light of the discussions held between Sri Lankan leaders and the Chinese delegation. Those discussions were largely about economic corporation between two countries – and of course the Chinese loans and investments.

Subsequent to these discussions, China provided 600 million renminbi ($90 million, or 16.5 billion Sri Lankan rupees) in grant assistance in an agreement signed by Wang Xiaotao, chairman of the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA). Local newspapers reported that during the visit of the Chinese delegation, there were discussions about obtaining a $500 million syndicated loan from China Development Bank (CDB).

A unique feature of a syndicated loan, or Foreign Currency Term Financing Facility (FTFF) as it is also known, is that the loan is not attached to a project, thus the Sri Lankan government has the liberty to use the loan money at their will. This is contrary to project loans, in which loan money should be strictly used only for project purposes. Hence, a project loan does not provide a way out from a balance of payment crisis in the short term. Often, when Sri Lanka has faced balance of payment (BOP) issues, they seek the support of the IMF, which provided short-term loans to strengthen foreign reserves, thereby assisting Sri Lanka to manage immediate BOP issues.

This scenario of seeking China’s financial support can be seen as an indication of shifting debt dynamics between Sri Lanka and China. It doesn’t mean that Sri Lanka would stop borrowing from China or significantly reduce obtaining Chinese loans, but it does indicate a change of the nature of Chinese loans obtained by Sri Lanka.

Prior to 2015, almost all Chinese loans were project loans, the majority of which were obtained from Chinese EXIM Bank for heavy infrastructure construction projects. These include Hambantota port, Colombo-Katunayake Expressway, and Mattala Airport. The money obtained through these project loans was not permitted to be used for other purposes. The government does not really have financial autonomy pertaining to these project loans (or, for that matter, any project loan obtained from the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, or Japan International Cooperation Agency). These loans therefore do not provide much support to overcome BOP crises, which have been a persistent issue faced by Sri Lanka.

In that context, Sri Lanka was compelled to focus beyond project loans and look at loan instruments that would assist them in managing BOP crises and short-term public finance issues encountered by the government. Syndicated loans were identified as a potential loan instrument (type of loan) that would assist the government with these short-term concerns as these type of loans have no restrictions in terms of spending. In addition, such loans are often provided at one go as opposed to several disbursements over a period of years, and give financial autonomy to the government, thus assisting the government to manage budget deficits as well as strengthen foreign reserves.

This is quite similar to the international sovereign bonds (ISBs) issued by Sri Lanka, through which dollar-denominated loans are obtained from international capital markets. ISBs provide this financial autonomy at the expense of high interest rates and short repayment periods. To put it in simple terms, the Sri Lankan government faces no restrictions on how it spends money lent through sovereign bonds. The government has freedom to use the money to carry out any project they would like.

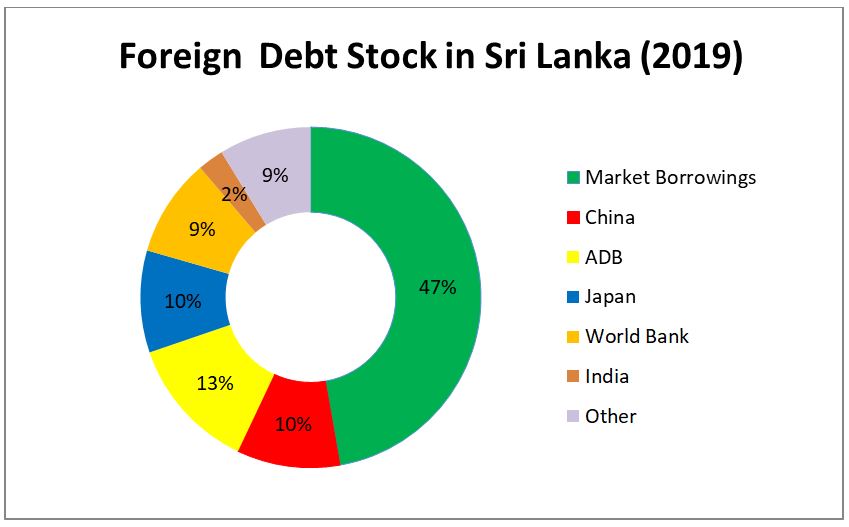

This financial autonomy, and the reduction of concessionary loans provided to Sri Lanka after its upgrade to middle income status, made ISBs a widely adopted method by successive Sri Lankan governments to obtain foreign loans. Sri Lanka issued its first ISB in 2007 and, as of the end of 2019, approximately 47 percent of its total foreign loans are ISBs. The short-term maturity structure of ISBs and the requirement to repay the principal payment at once put pressure on the BOP status of the country, as ISB maturities cause massive foreign currency outflows.

Data from the External Resource Department, Sri Lanka.

Against this backdrop, Sri Lanka started to look at alternative methods of foreign financing in order to reduce the pressure on its BOP. Obtaining a Foreign Currency Term Facility (syndicated loan) was one option. In 2018, the then Sri Lankan government obtained a $1 billion syndicated loan from China Development Bank. This loan was obtained at the USD LIBOR 6 month interest rate (a global benchmark), plus a margin of 2.56 percent per annum and a payback period of eight years (with a grace period of three years).

This loan was upsized in March 2020 and another $500 million syndicated loan was obtained from the CDB, including an extension of the payback period to 10 years. The interest rate too is an improvement over 2018, with the USD LIBOR 6 month rate in 2020 being less than that of 2018.

Future Public Debt Dynamics of Sri Lanka

The potential change in the approach to Chinese debt comes down to Sri Lankan economy’s chronic structural weaknesses, such as low exports and low tax revenue. Weak performances in the external sector, largely led by poor export performances and failure to attract sufficient foreign direct investment, have led the economy to suffer from persistent BOP issues. Tackling these issues require massive amounts of foreign financing each year.

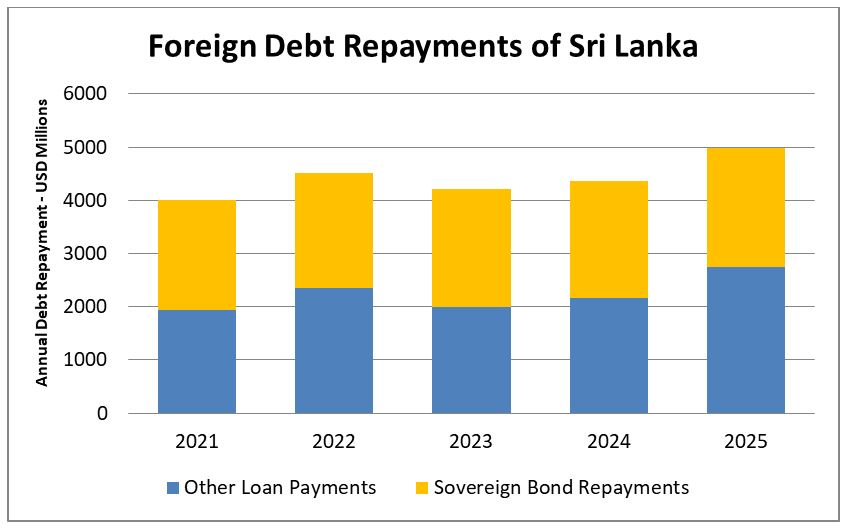

This development is likely to result in a few outcomes. In the next three years, sovereign bond repayments amount to $6.3 billion. In light of this, the Sri Lankan government might obtain more syndicated loans from China to bridge its foreign financing gap and manage foreign reserves, thereby tackling its BOP challenges.

Data from the External Resource Department, Sri Lanka.

In that context, it is possible that syndicated loans from China will be used as an alternative to raising money through issuing sovereign bonds. This will allow the government to diversify its debt portfolio and reduce the reliance on sovereign bonds. Within the next five years sovereign bond the Sri Lankan government is likely to use Chinese syndicated loans or such loans obtained from other lenders to finance a portion of large debt repayments instead of entirely relying on sovereign bonds. With the potential high interest to be paid on sovereign bonds due to the downgraded country ratings, syndicated loans would be an attractive alternative to the government.

It is also clear that the Sri Lankan government sees syndicated loans from China as an alternative to IMF loans to tackle BOP issues. The loan said to be negotiated during the visit of the Chinese delegation in October would assist the country to manage foreign reserves in the short term, thereby allowing it to avoid seeking the support of the IMF.

This potential scenario is likely to result in an increase in the Chinese portion of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt, with a potential reduction of the share of sovereign bonds. By the end of 2019, only 10 percent of Sri Lanka’s total foreign debt is owed to China while 47 percent of foreign debts are sovereign bonds. Such a shift will also significantly change the composition of Sri Lanka’s Chinese debt. By the end of 2019, nearly 85 percent of the Chinese loans were export credits, most of which were obtained from EXIM Bank of China. If Sri Lanka obtains the latest syndicated loan from China, that will increase the syndicated loan portion up to more than 25 percent of total Chinese debt. This figure is likely to increase given the possibilities of obtaining more syndicated loans in the future.

On a macro level, Sri Lanka’s foreign debt stock will rise. Given the low tax revenue, coupled with the restricted lending capacity of banks due to the loans provided for businesses during COVID-19 pandemic, the government will be compelled to borrow from foreign sources. Increasing reliance on foreign debt is also possible due to the significant reduction of export earnings, including the earnings from tourism, which also reduces foreign currency inflows. This will put more pressure on Sri Lanka’s ability to settle foreign debt payments, resulting in borrowing from foreign sources due to the dearth of foreign currency (dollar) inflows.

As a result, the foreign public debt stock of the country is likely to become larger than the domestic debt stock. Currently Sri Lanka’s foreign debt amounts to 42.6 percent of the GDP while the domestic debt stock amounts to 44.1 percent. Consistent issuing of sovereign bonds in order to finance foreign debt repayments (including previous sovereign bond maturities) had substantially increased the foreign debt stock in the recent past. In 2012, when the first sovereign bond maturity was due, Sri Lanka’s foreign debt stock amounted to 31.7 percent of the GDP; by the end of 2019, it had risen to 42.6 percent. Massive sovereign bond repayments in the upcoming years may result in foreign debt stock surpassing the domestic debt stock. It is likely that some Sri Lanka’s future sovereign bond repayments will be financed by Chinese loans, without relying on issuing still more sovereign bonds.

Umesh Moramudali is an economic researcher focusing on public debt dynamics and economic development in Sri Lanka. He is a Chevening scholar and holds an M.Sc in Economics from the University of Warwick. The opinions and analysis presented here are the author’s alone and by no means reflect the views of the institutions that the author is affiliated with.