South Korea has not been a major destination for immigration historically. Even today, most attention is focused on the 30,000+ arrivals from North Korea since 1998. Meanwhile, South Korea’s declining birth rate demonstrates a need for immigration, whether ethnically Korean or otherwise. Ethnic Koreans in the region often were provided visa privileges, yet struggled to integrate, while “mixed-blood” residents faced social and institutional discrimination. As non-Korean immigration slowly increased, tolerance for multiculturalism has lagged behind and has further been under analyzed, with discrimination and hostility toward immigrants still commonplace.

As a historically ethnically homogeneous state with less than 5 percent of the population immigrants, the assumption remained that the public preferred ethnic Korean immigration. Yet few studies directly identified whether there were preferences across ethnic Korean groups. For example in 2016 Shang E. Ha, Soo Jin Cho, and Jeong-Han Kang found that the South Korean public preferred North Koreans over ethnic Koreans from China (Joseonjok). Ethnic Koreans across the former Soviet Union (Koryo-saram), who were forcibly relocated away from the Korean border area by Stalin and who started arriving back in South Korea in the 1990s, also face discrimination and alienation. Those Joseonjok who maintained their Korean language commonly were treated more fairly by South Koreans than Koryo-saram, mostly from Uzbekistan, who often not did maintain the language.

Likewise, largely disparate and anecdotal evidence suggests South Koreans are concerned about non-Korean immigration both from elsewhere in Asia and from the Middle East, in particular. While North Korean arrivals increased since the famine of the 1990s, with a noticeably sharp decline this year, as many as half of South Korea’s immigrants consist of Chinese citizens, mostly of whom are ethnically Chinese, but also include ethnic Koreans originally living near the North Korean border. South Korea also attracts many others, such as Southeast Asians who come in as both foreign brides to rural workers and economic migrants for what is known as 3-D jobs (dirty, dangerous, and difficult).

Many of the concerns about economic immigration in South Korea parallel public concerns seen in other developed states. However, South Korea has also recently become a destination for asylum seekers as well. Burmese arriving since the 1990s have been caught in shifting categorizations of migrants and refugees. In addition, the arrival of Yemeni asylum seekers appeared to ignite latent Islamophobia and fuel claims that arrivals were just economic migrants and a threat to the safety of Korean women, with over 700,000 signing an e-petition to President Moon Jae-in opposing granting refugee status. African asylum seekers have found a similar hostility. Limited comparative research finds that majorities of South Koreans do not support accepting non-Korean and especially Muslim refugees, especially compared to accepting North Koreans. Meanwhile, limited evidence suggests that immigration from European and other Western countries does not elicit the same concerns, perhaps due to assumptions that such migration is short-term and often in areas of high demand (e.g. teaching English).

We wanted to directly test the extent to which the South Korean public differentiates among immigrant groups, and specifically to what extent various ethnic Korean immigrant groups in general or specific co-ethnic immigrants are preferred to non-ethnic Korean immigrants. In addition, we wanted to identify whether South Koreans may just be hesitant to support immigration of any kind.

To tackle these issues, we surveyed 1,200 South Koreans during September 9-18, via a web survey conducted by Macromill Embrain, using quota sampling by region and gender. We randomly assigned respondents to one of eight prompts to evaluate on a five-point scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree).

The prompts were:

“The South Korean government should encourage…

Version 1: “… ethnic Koreans abroad to move to South Korea”

Version 2: “…North Koreans to move to South Korea.”

Version 3: “…ethnic Koreans from China to move to South Korea.”

Version 4: “…ethnic Koreans from Central Asia and Russia to move to South Korea.”

Version 5. “…Europeans to move to South Korea.”

Version 6: “…Southeast Asians to move to South Korea.”

Version 7: “…Africans to move to South Korea.”

Version 8: “…Middle Easterners to move to South Korea.”

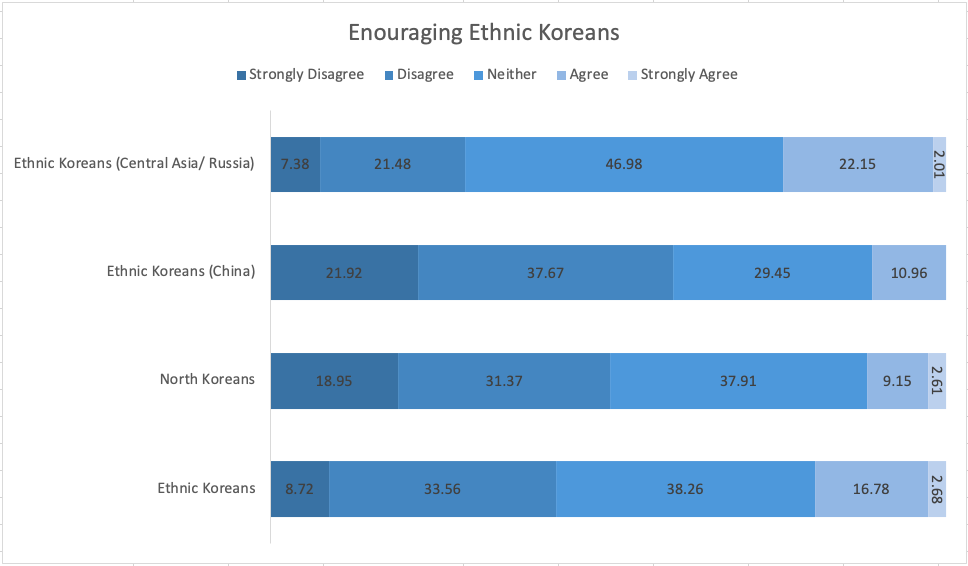

Starting with ethnic Koreans, we find the undifferentiated prompt (Version 1) elicits more opposition (42.28 percent) than support (19.46 percent). This suggests perhaps an acknowledgement of the limits to what South Korea can absorb, even if ethnic identity remains strong. Among the three differentiated ethnic Korean groups, less than 30 percent agree than South Korean should encourage immigration.

The group South Koreans are least likely to want to encourage to move to South Korea are ethnic Koreans from China (59.59 percent), followed by North Koreans (50.32 percent). One possible explanation for this could be that North Koreans receive government assistance after defecting to South Korea, and therefore are commonly viewed as an economic burden on the country. Ethnic Koreans from China likely are viewed as economic migrants than refugees. Moreover, the disapproval of Korean-Chinese immigration may be caused in part by the outbreak of COVID-19, which has caused a rise in Sinophobia across the globe.

Interestingly, the figure above shows that South Koreans are most likely to agree with encouraging ethnic Koreans from Central Asia or Russia out of all the ethnic Koreans mentioned. This is especially fascinating when considering the wide difference of treatment between Koreans from Central Asia and North Koreans, as the latter are automatically granted citizenship. The data perhaps suggests that South Koreans are more sympathetic to the forced migration of ethnic Koreans under Stalin and the particular hardships they face in establishing citizenship in South Korea. However, even here, only 24.16 percent of respondents agreed that ethnic Koreans from Central Asia and Russia should be encouraged to immigrate.

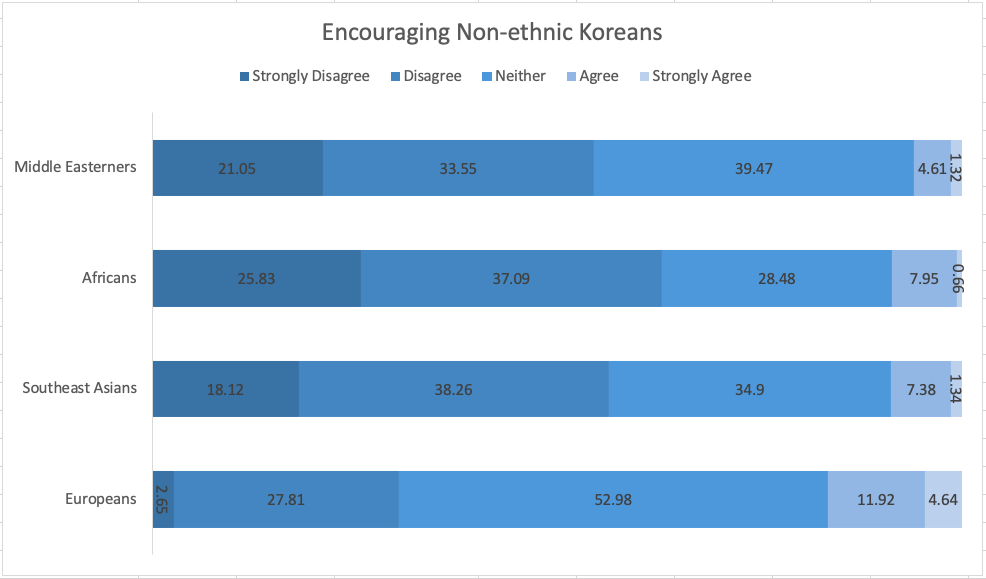

South Koreans were even less likely to agree with encouraging non-ethnic Koreans to move to South Korea. In particular, 62.92 percent either disagreed or strongly disagreed with encouraging Africans to move to South Korea, with majorities not supportive of encouraging Middle Eastern (54.6 percent) or Southeast Asia migration (56.38 percent) either.

In contrast, Europeans seem to be an outlier for views on non-ethnic Koreans with only 30.46 percent of South Koreans disagreeing with encouraging their immigration. Of all groups, European immigration was the only group in which a majority of respondents (52.98 percent) stated they neither disagreed nor agreed with encouraging immigration. Notably, more people supported encouraging Europeans to immigrate to South Korea than similar encouragement for ethnic Koreans from China or North Koreans. This not only suggests the limits of shared ethnic identity, but suggests perceptions of an economic burden of these co-ethnic groups, compared to immigration from more economically affluent European countries.

Comparing both figures, we can see that South Koreans overall are more welcoming toward ethnic Koreans, but not by wide margins, with most respondents hesitant to encourage immigration of any group. This suggests factors beyond ethnic identity, perhaps economic burden, playing a crucial role.

Previous studies find that perceptions differ across demographic groups, with younger South Koreans more accepting of immigrants regardless of their ethnicity and men being marginally more supportive than women. We ran separate statistical models for support of each immigration version for basic demographic factors (gender, age, education, household income) as well as political ideology and pride in being Korean. We find age positively corresponds with greater support only in Versions 1, 3, and 4, but in none of the non-ethic Korean models. Surprisingly, the ethnic pride variable was only statistically significant in Version 1. In other words, respondents proud to be Korean were more supportive of encouraging ethnic Korean immigration, but this did not translate to greater support for specific ethnic Korean groups.

These results have clear ramifications in the lives of South Koreans and South Korean immigrants. First, despite sharing an ethnicity and often cultural practices, South Koreans are hesitant to accept the notion that co-ethnics should all live in one state. Part of this may be due to the economic burden of ethnic Korean immigration from the region, but may also indirectly suggest that the public’s view of a shared identity is weaker than outside observers may have assumed. Secondly, the findings suggest not only concern about immigration from poorer areas and perhaps the potential for more asylum seekers arriving in South Korea, but immigration as a whole.

Taken as a whole, the public’s hesitancy to support immigration may partially explain the limited attempts by the government to promote less restrictive immigration laws or programs that aid those already in country. That South Koreans rarely interact with immigrant communities likely exacerbate this problem. Without efforts to encourage such contact, South Korea may continue to struggle to encourage the integration of immigrants into society.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University and director of the International Public Opinion Lab (IPOL). His research focuses on public opinion and electoral politics, with a focus on East Asian democracies.

Carolyn Brueggemann is an honors undergraduate researcher majoring in International Affairs and Chinese at Western Kentucky University.

Kaitlyn Bison is a recent honors graduate of Western Kentucky with a bachelor’s in International Affairs and Economics.

Michael King is a recent graduate of Western Kentucky University and a 2018 Gilman Scholarship Recipient with a bachelor’s degree in International Affairs, Political Science and Asian Religions & Cultures.