As even the most inattentive observer of contemporary international politics will attest, technological competition – mostly, but not always, between the U.S. and its allies on one hand, and China and Russia on the other – has once again risen to the fore. Analysts, so far, have approached this issue from various angles: what it means in terms of military balances, the possibility of international cooperation, what a technological edge implies for domestic policies, and so on. The outgoing Trump administration has made technological contestation with China a cornerstone of its strategic policy, emphasizing the need for the United States to maintain its edge when it comes to artificial intelligence (AI), quantum information science, and aerospace and other critical technologies, among others.

Other Indo-Pacific powers, such as Australia, India, and Japan, have also joined the fray in pushing both new and emerging tech at home as well as promoting collaboration around it between “like-minded countries.” In June this year, a Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence of 14 states along with the European Union was launched, to facilitate collective AI research as well as implementation. Australia and India have committed to work together across a range of critical technologies, including AI, while the Pentagon is looking to jointly collaborate on AI-related technologies and use-practice with allies and partners. U.S. think tanks have also issued reports that look at the possibility of greater international collaboration on AI and of developing an “alliance innovation base.”

AI Collaboration: The What and Why

At the same time as technological competition has heated up, the strategic construct of the “Indo-Pacific” – whose geographic extent covers the Indian Ocean and the Pacific – has come to the fore, the key advocates of which have been the very same actors that have paid close attention to the role new and emerging technologies can play in determining future geopolitical balance: Australia, India, Japan, and the United States, among others. These actors have noted the need for the Indo-Pacific region to be “free,” “open,” “resilient,” and “inclusive.” Operationally, what these adjectives mean is that the Indo-Pacific remains free of Chinese coercion, economic and otherwise; that it is open in terms of not allowing exclusive territorial claims that run against the grain of global-commons principles; and – this has come to the fore especially during the coronavirus pandemic – is resilient to shocks. To this desideratum has been added the need for the region to be “inclusive,” meaning that visions for the Indo-Pacific include all regional powers, their needs and views. Concerns around China’s grey-zone coercion and hybrid warfare and its regional infrastructure diplomacy have compounded worries about the balance of military power in the Indo-Pacific shifting decisively in favor of China in the minds of many regional actors.

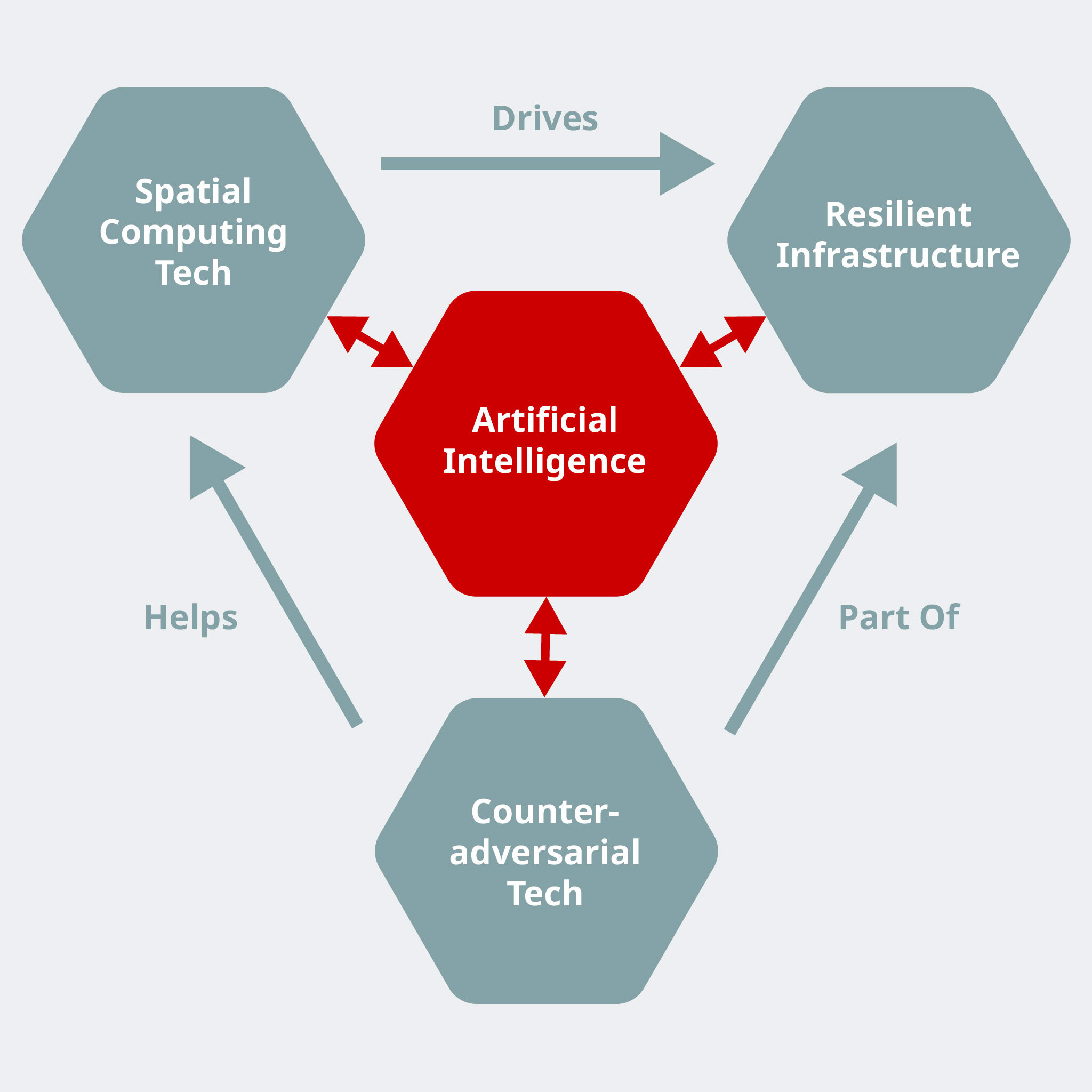

In what follows, I identify three technologies around AI for regional collaboration that can help further the free, open, resilient, and inclusive nature of the Indo-Pacific in the medium term, up until 2030. I do so by assuming that extant technological trends will hold over the next decade and that both challenges and opportunities in the region will be what they are today. In terms of their strategic use, I identify:

- Spatial computing technology as means to maintain the open character of the region, given its ability to make the most out of geospatial information, and therefore its use to augment traditional military capabilities;

- Resilient smart infrastructure as a means to re-energize the region’s ability to absorb shocks to social-technical and physical infrastructure;

- “Counter-adversarial technologies” that can help regional actors combat disinformation as well as emerging forms of cyber-attacks, and therefore maintain the region’s free character by enabling them to resist non-kinetic coercion.

But all three technologies identified here also have extensive commercial and public-welfare uses, which brings me to the inclusive part of the agenda: the idea behind choosing them is also to encourage participation of those countries in international AI collaboration which, for one reason or the other, have little incentive to jump in head first into the China-U.S. contest, and would instead prefer a more constructive agenda for tech cooperation that addresses their specific circumstances.

AI-related technologies for the Indo-Pacific (Graphics: The Diplomat)

A pedantic note: I use AI and machine learning (or its sub-branch, deep learning) interchangeably for what follows, the full knowledge that this is an abuse of terminology.

Spatial Computing Tech

Spatial computing, very generically put, is the assortment of computing technologies that enable humans to enhance their interaction with their geographical environment. As computer scientist Shashi Shekhar put in in a 2019 co-authored book on the subject, “spatial computing is a set of ideas and technologies that transform our lives by understanding the physical world, knowing and communicating our relation to places in that world, and navigating through these places.” We are all familiar with spatial computing applications, ranging from the global positioning system, to remote sensing and geographical information systems. But that’s just the beginning. Evangelists of spatial computing peer into the near future and see possibilities in spatial predictive analytics (techniques to detect useful patterns in geographical and spatial data), a “location-aware Internet of Everything (IoT)” (that links mobile to fixed smart objects) as well as seamless integration of data from outdoor, indoor, underwater, and underground geographical environments.

But most striking among the possibilities offered by spatial computing is that of augmented reality systems. As three experts on the subject define it, “Augmented reality enriches our perception of the real world by overlaying spatially aligned media in real time.” While the military applications of augmented reality are known, so are its commercial possibilities, as the makers of the 2016 mobile game Pokémon Go, which utilized it, would attest.

Tech guru Kevin Kelly sees in augmented reality the exhilarating possibility of a “mirror world.” As he wrote in an influential essay in Wired last February, “Someday soon, every place and thing in the real world – every street, lamppost, building, and room – will have its full-size digital twin in the mirrorworld.” If such a scenario was to eventuate, the security challenges should be obvious, given the tenacity and opportunism of state-sponsored hackers in the Indo-Pacific. Kelly went on to add: “Everything connected to the internet will be connected to the mirrorworld.” And, if current IoT predictions along with Kelly’s confident prognostication hold – one forecast suggests that 50 billion devices will be connected through a massive web in 2030 – augmented reality would very well be what presents completely new possibilities as well as threats.

AI and spatial computing have an integral relationship. As the number of sensors and effectors increase in a geography, the data they collect about their spatial environment will be fed to develop smarter machine-learning models which, deployed on IoT devices, will create a virtuous loop in terms of the adoption of AI.

Resilient Infrastructure

Even before the pandemic hit, resilience – the ability of man-made socio-technical and physical systems to absorb and survive sudden natural or artificial shocks – was on the minds of many in the Indo-Pacific. When the MIT Technology Review asked experts on their predictions for 2030 in the sidelines of Davos this year, director of the 3A Institute and senior fellow, Intel (Australia), Genevieve Bell included future recognition of how 20th-century infrastructure has failed to deliver. As Bell put it, “we’ll have to contend with the fact that all the infrastructures of the 20th century – electricity, water, communications, civil society itself – are brittle, and this brittleness will make the 21st century harder to deliver.” The pandemic has only underscored her point, with how the U.S. health infrastructure dealt with the novel coronavirus being just one (disturbing) data point. To take another example: Southeast Asia is routinely hit with cyclones, and yet responses of regional governments remain subpar.

When it comes to physical infrastructure, experts routinely speak of “smart cities” (ASEAN, for example, has a Smart City Network Action Plan) as the panacea for all that ails urban living environments. Setting aside the fact that there is no universally accepted definition of what constitutes “smart” when it comes to cities, and that the notion itself is contested, at the bare minimum, a smart city necessarily is one that is networked, with information and communication technologies helping address challenges from urbanization, ranging from traffic management to garbage disposal.

A focus on smart cities makes a lot of sense looking at projections around the region’s future – in 2018, the United Nations projected that by 2050 half of all Asian countries will have more than 74 percent of their population living in cities. Layer on top of this the explosive expected growth in the number of IoT devices, as well as possibilities emerging from spatial computing, and a new notion of resilient infrastructure for the Indo-Pacific emerges, in which AI and other automated systems contribute to resilience by leveraging seamless integration of geospatial data from “everyday” smart devices – such as internet-enabled cellphones – with early warning surveillance systems. If this sounds abstract, think of a possibility where governments are able to automatically identify geographically, at a granular level, individuals and populations vulnerable to an incoming shock (such as an infectious-disease outbreak or inclement weather) and guide them to appropriate relief facilities (such as hospitals and shelters).

Counter-adversarial Tech

A key issue that has, time and again, come up on the strategic agenda for the Indo-Pacific is the need to fight disinformation. At many levels, after the rampant adversarial use of social media to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential elections by entities connected to Russian intelligence, this challenge is commonly known. Social media giants such as Facebook have also found themselves under increased scrutiny as their websites and applications have been deftly manipulated by certain actors to spread disinformation in order to attain specific political goals.

But one of the ways through which technology can help combat the spread of disinformation and speech designed to incite violence is through machine-learning tools. Facebook and Google have both developed AI-based tools – Deeptext and Perspective, respectively – that combat online trolling and hate speech. While these tools still require considerable participation from human moderators to be truly effective, progress continues to be made. A June 2020 RAND Europe study, commissioned by the U.K.’s Defense Science and Technology Laboratory, shows that machine learning algorithms were able to detect malicious actors, including Russian trolls, in social media. Facebook has also relied on AI to detect COVID-19-related disinformation on its platform, and have used a machine learning-based solution to block advertising around masks, testing kits, and other pandemic-related items. The United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is also heavily invested in research into the detection of “deepfakes” – AI-generated videos and images that are virtually indistinguishable from real ones.

But disinformation, including through deepfakes, is only half of the challenge when it comes to malign actors seeking to contaminate and exploit the collective information pool. Increasingly, researchers are becoming cautious about the possibility of “adversarial machine learning,” a set of techniques hackers and other malicious players may utilize to exploit inherent vulnerabilities in how a machine learning model comes to be and is deployed. As one collective research effort of industry majors and academic institutions put it in a tutorial on the subject, the “methods underpinning the production machine learning systems are systematically vulnerable to a new class of vulnerabilities across the machine learning supply chain,” which adversaries will seek to tap into.

These include specific targeting of either the training or the inference parts of the supply chain – or both. One adversarial machine learning attack is “model poisoning” where an attacker “contaminates the training data of an ML system in order to get a desired outcome at inference time.” One industry report notes that 30 percent of all cyberattacks in 2022 will be instances of adversarial machine learning. Increasingly, as the IoT leads to even greater proliferation of AI-enabled systems, research into adversarial machine learning will require further sustained efforts and international collaboration.

The Why Question, Revisited

As has often been said before, between techno-optimism and techno-pessimism lies techno-realism. In this sketch, I have attempted to be both prospective as well as prescriptive. This article is prospective in the sense that what has preceded is based on the extrapolation of current trends around both where the Indo-Pacific stands in terms of its needs as well as extant technology; the preceding has been a description of things very likely to materialize, irrespective of one’s normative position around it. But this article is also an exercise in prescription: of areas around which regional powers can profitably, and even informally, collaborate, assuming that they continue to expect a free, open, inclusive, and resilient Indo-Pacific.

But an international collaborative approach to technology, involving both states and non-state actors such as commercial entities, also has a powerful institutional externality, in that the norms around its use can be more easily socialized. This, in turn, has a geopolitical function. Concretely: take the preceding discussion around smart surveillance and resilient infrastructure. As is painfully obvious, China’s pursuit of AI-driven surveillance has not only impacted its own ethnic minorities, but it has also “socialized” the use of such tech to countries across the world, including known authoritarian states. But if an Indo-Pacific technology coalition was to emerge that, instead of calling for nations to eschew all use of smart surveillance, jointly devised ways to develop and ethically deploy it, it automatically becomes a powerful counterweight to China.

As a concluding thought: no technology, not even AI, is a silver bullet when it comes to maintaining a relative advantage over geopolitical contenders; international politics is too complicated than that. But something as alluring as AI can gather states together as they confront a range of challenges, given that many them can be – directly or indirectly – addressed by it.