For Korea watchers, U.S. President Donald Trump’s narrative that Democrats, backed by foreign powers, have “stolen” the election through massive voter fraud uncannily resembles a widespread conspiracy theory that emerged in South Korea following its legislative election on April 15. Both narratives suggest that the liberal/progressive parties colluded with “China” to tamper with ballots, in elections that were expected to – and indeed did – benefit the progressives.

The convergence of the narratives on electoral fraud in South Korea and the United States is not a coincidence. Different forms of the American far-right’s discourses and practices have been adopted by its Korean counterparts, from the emergence of fringe media outlets that stand in opposition to the “mainstream media,” to the widespread use of Pepe the Frog memes on fringe sites. Furthermore, an increasingly assertive Beijing has made it easier for South Korean conservatives to rally around their existing anti-communist identity and accuse progressives of colluding with outside enemies, a stance that fits neatly with the narratives from the U.S.

But this is not merely a tale of two similar narratives or a frivolous double-take on fringe conspiracy theories. It brings attention to the domestic contexts that have allowed these conspiracy theories to emerge out of the fringe, as well as the potential of greater challenges. The American struggle with right-wing populism has been well-documented already, and this article instead focuses on the South Korean context, which has received relatively less attention. The movement questioning the results of the April 15 election in South Korea highlights factors in its political landscape that may further disrupt the foundations of its democratic system in the same way that the election of Trump has done in the U.S., and it underscores the transnational element of today’s right-wing politics, which act both at the domestic and international levels.

Beijing’s “Dark Shadows” Extending from Seoul to Washington?

Preparing for the election amid a COVID-19-struck economy and unfavorable polling numbers, Trump had been suggesting for months that the election might get “stolen” by Democrats and foreign actors like China. In particular, the Trump campaign problematized the increased use of mail-in ballots. In August, Trump said, “The mailmen are going to get them, and people are just going to grab batches of them … [China and Russia], they’ll be grabbing plenty of them. It’s a disaster, it’s a rigged election waiting to happen.”

As expected, once it became apparent that the election would not be going his way, Trump started to call the mail-in ballots “illegal,” and launched numerous legal battles. Foreign Policy’s James Palmer warned that Trump is likely to take up the conspiracy theories circulating in the right-wing Chinese media that link Biden to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

As Trump started to make claims of “illegal ballots,” Min Kyung-wook, an ex-member of the South Korean National Assembly, wrote on November 5 that the “dark shadows” of the April 15th election that unseated him had “extended” to the U.S. presidential election, referring to Joe Biden’s expected victory. Drawing a parallel between the two elections, Min pointed to the CCP and “leftist factions” allegedly collaborating with Beijing as the forces behind the acts of electoral fraud in both the U.S. and South Korea.

A former prime-time news anchor at Korean Broadcasting System, Min has been spearheading the movement to raise awareness about alleged electoral fraud since losing his seat in the April 15 legislative elections, in which his party, the United Future Party (now the People Power Party), suffered a landslide defeat. Min started to bring to the surface internet conspiracy theories claiming that advance votes had been tampered with in order to hand a landslide victory to the ruling Democratic Party of Korea.

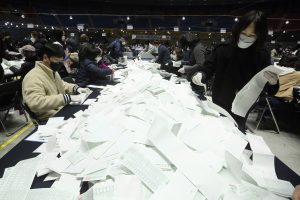

South Korea’s April election saw a record 26.7 percent of voters casting their ballots in advance, with the National Election Commission and the political parties encouraging voters to do so amidst the pandemic. Similar to the U.S., voters who voted early favored the progressives. For instance, in Seoul, the Democratic Party led the United Future Party by 26.76 percent in advance voting, while the margin was reduced to 1.35 percent in regular voting. Also, the ballots cast in advance were counted after the regular votes, so several races where the United Future Party was leading flipped at the last minute, much like Pennsylvania and Georgia in the U.S. election.

Shortly after the election, Min publicized far-right conspiracy theories about the election that had been circulating on the internet. He pointed out that the ballot boxes containing advance voting ballots were stored in places without CCTVs, and highlighted the discrepancy between the results of early and regular voting. Min obtained crushed ballots – some of them believed to be stamped by the authorities – from an observer and presented them as further evidence of election tampering. He also problematized the QR codes on advance voting ballots, suggesting that these contain the personally identifiable information of 5 million Korean citizens, including records on criminal activities, military service, tax payments, and so forth.

The China Factor

A critical element of Min’s claims is that Beijing was involved in the electoral fraud that allegedly took place during the April election, colluding with leftist forces in power that are sympathetic to the Chinese agenda. Min made an unsubstantiated – and ultimately refuted – claim that Chinese tech giant Huawei supplied 700 pieces of election equipment to the National Election Commission and that the personal information obtained through QR codes was transmitted to the Chinese. He also presented a numerical arrangement and claimed that this was a code that read “FOLLOW_THE_PARTY,” left by a Chinese hacker who had infiltrated the NEC’s system.

Such a narrative exploits anti-Chinese sentiments, which remain extremely high in South Korea. According to a Pew Research poll, the percentage of South Koreans viewing China unfavorably jumped from 31 percent to 75 percent between 2002 and 2020. In addition to the current pandemic and recent controversies over the suppression of protests in Hong Kong and revelations of human rights abuses in Xinjiang, South Korea’s direct exposure to an increasingly influential and assertive China has played a role. For instance, the installation of U.S. anti-missile systems in the country in 2016 led Beijing to impose a wide-ranging “ban” on South Korean products, which brought to public attention the country’s economic reliance on China and created a collective sense of resentment toward a more assertive Beijing.

The current political context plays a role in it as well. Under President Moon Jae-in, South Korea has been attempting to rebalance its relationship between Washington and Beijing. While Japan and the Five Eyes allies have banned Huawei from bidding for 5G contracts, Seoul has left the Huawei question to be decided by the private sector, and it has not prevented LG U+ from using Huawei equipment in its 5G network. Further, Seoul has remained either silent on or slow to respond to concerns such as the re-education camps in Xinjiang or the passage of the new National Security Law in Hong Kong, issues that have provoked criticism from other democracies.

Conservatives, who generally support the alliance with the U.S., have been criticizing the current administration for being too soft on China, and the far-right has activated existing Cold War identities that label progressives as “reds” or “commies.” In this context, Min leveraged Sinophobia, both domestic and foreign, to strengthen the claims that Beijing interfered in both elections. For instance, Min borrowed the unsubstantiated report, circulating among U.S. conspiracy theorists, that 20,000 fake IDs from China and Hong Kong were seized at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, as well as the claims that Hunter Biden is involved in lobbying activities with the Chinese. The mail-in ballots controversy and the victory of Joe Biden, for Min, reinforces the idea that there is a transnational group of leftists – from Seoul to Washington – who are collaborating with Beijing to undermine the liberal world order, which gets us to the culture war.

Culture War

Min’s campaign to expose the alleged electoral fraud has been supported by right-wing, independent media on online platforms. In recent years, YouTube has seen explosive growth in South Korea; based on data from Android users, the number of YouTube users increased by 38 percent to 34 million between 2016 and 2019, and the hours of content uploaded to Korean YouTube channels grew by 50 percent between 2018 and 2019. The increase in popularity – and profitability – of YouTube channels has attracted numerous celebrities and content creators, including right-wing commentators who have not been able to find a platform in mainstream media.

Most of the top South Korean YouTube channels in the politics category lean toward the right. Ranked by total video views, eight out of the top 10 channels in this category have a right-wing stance. Shinuihansu, the top-ranked channel, has over 1.3 million subscribers and 978 million views, and Jin Seong-ho Broadcasting has 1.1 million subscribers and almost 800 million views. These channels are run by former politicians and journalists who have connections and insider knowledge. Their easy-to-digest “news briefings” have become extremely popular among conservatives in South Korea – especially the elderly, who share these clips via KakaoTalk, the omnipresent Korean messaging app.

Many of these YouTubers have wholeheartedly embraced the U.S. style of “culture war” against “leftists,” whom they deem to be present not only in politics but also in the arts, academia, and the private sector, in cahoots with Chinese capital. For instance, the Garo Sero Institute’s YouTube channel, which has over 600,000 subscribers and over 315 million views, has been referring to the institute’s activities as a “cultural war.” The channel features Kim Yong-ho, a former entertainment journalist, and Kang Yong-seok, a former member of the National Assembly, both of whom have not been shy about exposing the private matters of celebrities and sharing unsubstantiated reports. The goal is not only to draw attention to their political commentaries but also to harness gossip and fake news in service of the culture war against the left. They have obviously taken their playbook from the U.S. alt-right, which has been linking the left with Hollywood. The Garo Sero Institute’s Kim produced a film titled “Parasite Family,” which makes a direct reference to the ongoing scandal over the Moon government’s former justice minister, in a manner similar to Dinesh D’Souza.

What Are the Implications?

To be clear, the “mainstream” in both the U.S. and South Korea has responded to these claims of electoral fraud with swift dismissal. However, in the era of “alternative facts,” the space that the “mainstream” occupies is under constant challenge, and these “fringe theories” have come out of the fringes, with prominent political figures in “mainstream” parties, like Trump or Min, behind them. The context in the U.S. that has led to the resurgence of the far-right has been well-documented and analyzed, and it might be necessary to continue watching this space in South Korea, which seems to be mirroring the U.S.

In his recent book “Why We’re Polarized,” Ezra Klein writes about how what he terms “mega-identities,” which organize diverse identities along two-party lines, have contributed to what seems to be an irreconcilable partisanship in the U.S – and South Korea might be headed in the same direction. Although the impeachment of President Park Geun-hye in 2016 has been celebrated as a sign of South Korea’s democratic maturity, this may have been South Korea’s Obama moment, which clearly demarcated the end of the old South Korea symbolized by Park and her father, the authoritarian leader Park Chung-hee, and the beginning of the new South Korea of the “Candlelight Revolution.”

South Koreans remain divided over gender issues; immigration and race increasingly raise controversies on a national scale, as observed in the case of Sam Okyere earlier this year. In addition, consider voters’ disappointment with Moon’s progressive administration, which has failed to get the country out of “Hell Choseon.” The administration has been beset with alleged abuses of power by its appointees – the precise reason Park was dethroned – and economic policies that have failed to address concerns such as rising housing prices.

Meanwhile, the geopolitical tension between the U.S. and China will further pressure South Korea, the perennial “shrimp between two whales,” further activating Cold War identities on the far-right. Right-wing demagogues will continue exploiting the idea of a transnational cartel of leftists, corrupted by Chinese capital, collaborating with Beijing to undermine the liberal world order in all sectors, from entertainment to government.

The context of Min’s quixotic crusade reveals a South Korea that displays conditions of intense political polarization akin to that of the U.S. under Trump, one that has presented tempting opportunities to Min and other far-right activists. The growing influence of far-right YouTube channels seems to be both a symptom and cause of this polarization, and they are increasingly seeping into the “mainstream.” Of course, conditions do not equal causation, but it definitely presents risks to South Korea’s democracy.

Ultimately, in South Korea, we see the ramifications of a different type of interdependence between the far-right, which has reactivated Cold War identities, and the backdrop of decentralized platforms, culture wars, and a new geopolitical rivalry. The South Korean case highlights yet again how the erosion of democratic norms in the U.S. is not merely a domestic affair but one that has real, tangible consequences beyond its borders.

Dongwoo Kim is a program manager at Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, specializing in digital technology governance. He is a graduate of the University of Alberta, University of British Columbia, and the Yenching Academy of Peking University.