Europe is often seen as a divided continent – and in recent years these divisions have been discussed explicitly in relation to China. It is true that differences among European countries exist, but there is also a solid common ground among the EU members, which does not usually get spotlighted. A recent survey of more than 19,000 respondents in 13 European countries organized by Palacky University Olomouc in Czechia, offers perhaps the broadest and most detailed insights into European public attitudes toward China. The full report, on which parts of this text are based, is available here.

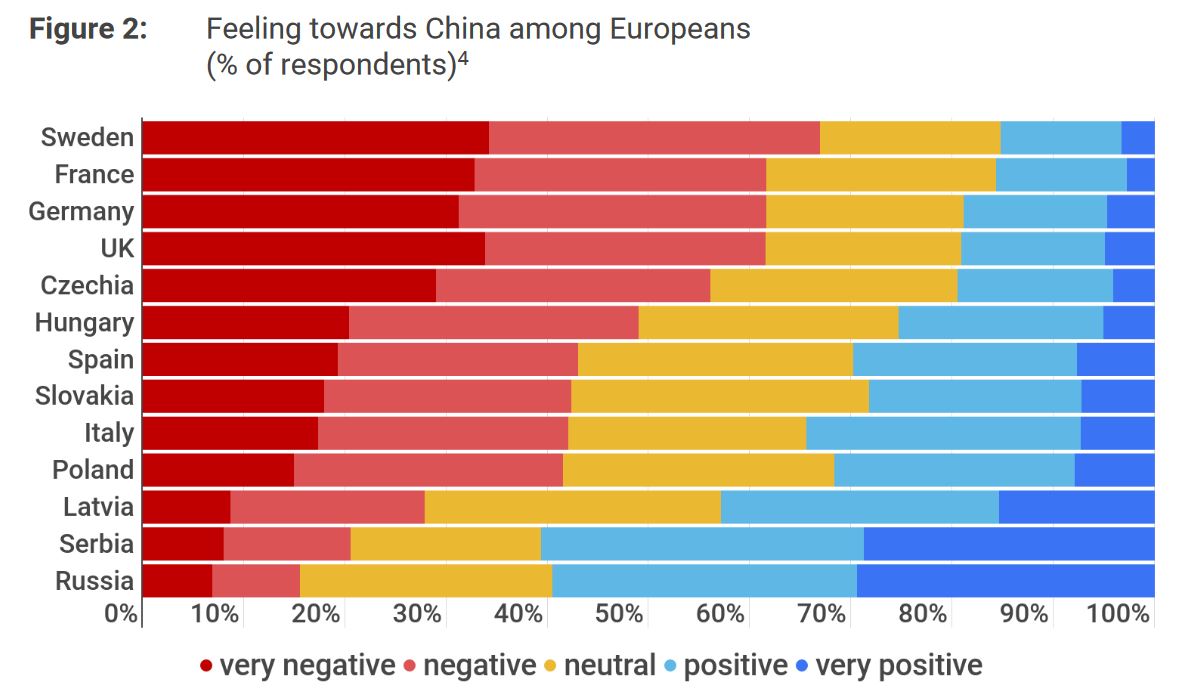

Overall, the image of China in Europe is prevailingly negative and got significantly worse during the previous three years. Countries in the west and north (Sweden, France, the U.K., and Germany) tend to have the most negative views, while the countries in the east (Russia, Serbia, and Latvia) are predominantly positive. Southern (Italy, Spain) and Central Europe (Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia) can be found somewhere in between, although still decisively negative.

The picture is similar when looking at how the respondents themselves evaluate the change in their views of China within the last three years. The U.K. reports the most significant worsening of the view of China, followed by Sweden, France, and Germany. Serbia is by far the country with the most significantly improved image of China, while Russia and Latvia also have more respondents reporting their views of China improving rather than worsening.

From the report “European public opinion on China in the age of COVID-19.”

A few factors seem to drive these perceptions. The countries with more negative views tend to be those which have experienced tense diplomatic relations with China in recent years, at least partly due to China’s increasingly confrontational diplomatic style. This applies especially to Sweden, but also to France, the U.K., or Czechia. On the other hand, countries like Slovakia or Latvia did not experience such diplomatic incidents and their views of China are still largely neutral or positive. The survey results can be thus seen as giving some evidence that China’s “wolf warrior” diplomacy contributes to the negative and worsening image of China in the EU.

The COVID-19 pandemic was recognized as the most common association with China overall and also in most countries, including Italy, France, Germany, and Spain. Exceptions to this are also telling – on the one hand, in Sweden and Czechia, China is associated by respondents primarily with “dictatorship” or “communism,” respectively. On the other hand, in Russia, Serbia, Latvia, and Slovakia, first associations of China tend to be more neutral, such as being a “large country” or even positive with recognition of cultural icons like the Great Wall.

Significant amounts of respondents in most countries recognize China’s help during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in Serbia, Italy, and Hungary. At the same time, few respondents believe that China’s international reputation has improved as a result of COVID-19. Interestingly, a high numbers of respondents believe unproven theories that the virus was “artificially created in a Chinese lab and spread intentionally” or that the virus spread due to “Chinese people eating bats and other wild animals.” This may suggest high levels of suspicions and also cultural stereotypes – and obviously point toward very low levels of soft power attraction to China.

When looking at various issues in relation to China, only trade is perceived as predominantly positive in most – yet still not all – countries. In comparison, Chinese investments and the Belt and Road Initiative are perceived more negatively, with only a few countries (Russia, Serbia, Latvia, Italy, and Poland) leaning toward the positive. This suggests that China is not seen across Europe as simply an “economic opportunity.” While for some countries, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, the promotion of trade and investments still scores as one of the most preferred policies toward China, the public in Western Europe has other priorities.

In all 13 countries, human rights situation in China is seen negatively, including in Russia or Serbia, where otherwise positive images of China prevail. At the same time, the respondents in those countries, but also in Latvia and Slovakia, do not want to engage in advancing human rights and democracy as a policy option. Instead, human rights are seen as an important issue to be upheld in China policies in Sweden, Poland, Italy, Germany, and the U.K.

Europeans do not feel overly threatened by China’s military or geopolitical expansion and are not willing to engage in a geopolitical competition. Still, cybersecurity is seen as one of the most severe issues to be addressed in relation to China.

Interestingly, the most negatively perceived issue in relation to China turned out to be its impact on the global environment, where respondents in all 13 countries have a decisively negative perception. This probably also explains why the most preferred policy option across the continent is the cooperation on global issues, with all countries’ respondents selecting it either as the first (such as Germany, Russia, Italy, and Hungary), second (Sweden, Spain, France) or third (the U.K.) most preferred policy. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has probably had an impact, too.

Do public views of China play any role in policy, one may ask? The survey results suggest they do. There are correlations between the public attitudes and the policy approaches that the governments have been taking. Focusing on 5G networks, for instance, respondents overtly support cooperation with companies from the countries they see positively and whom they trust. As such, with the exception of Russia and Serbia, all other countries favor cooperation with European companies, followed by Japanese and U.S. ones.

More in-depth insights based on this survey research utilizing more sophisticated tools will follow. Already the first results, however, bring some important takeaways, discussed here. The EU members are relatively unified in their approach toward China, especially when compared to non-EU countries such as Russia or Serbia. Although China’s human rights situation is seen as universally negative across the continent, Europe as a whole sees China’s environmental impact as the most negative issue and favors cooperation with China on global issues, while it does not want to engage in a geopolitical struggle with it. It is likely that these attitudes will impact the EU policy approach toward China, and also its relationship with its main ally, the United States.

Richard Q. Turcsányi is a program director at Central European Institute of Asian Studies, Palacky University Olomouc, and assistant professor at Mendel University in Brno, both in Czechia.