In what has become a yearly ritual, columnists in Western newspapers used this week’s BRICS’ Leaders Summits to question the grouping’s existence and predict or recommend its demise. In the Wall Street Journal, Sadanand Dhume argued last month that “the five-member club makes less sense than ever” and recommended that, “instead of building up Brics, India should help dismantle it.”

These same arguments have existed for nearly a decade. Just like in 2011, when the Financial Times’ Philipp Stevens announced that it was “time to bid farewell to BRICS,” writers point to the many differences between the five member countries, contrasting China’s and Russia’s authoritarian political systems with democracy in Brazil, India, and South Africa, and pointing to conflicting geopolitical interests and fundamentally different economic realities.

And yet, the BRICS countries stubbornly hold not only yearly presidential summits, but also regular consultations between foreign ministers and national security advisors, along with countless yearly meetings in other areas, including public health, agriculture, and education. Most remarkably, even the election of Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right populist who admires the United States and frequently attacks China, as president of Brazil has not noticeably altered the group’s commitment to continuing its process of slow institutionalization.

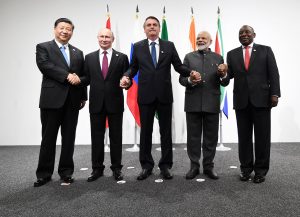

During the past years, BRICS summits have seen their fair share of tensions, to be sure. During the grouping’s 11th Leaders Summit in Brazil last year, Bolsonaro canceled the BRICS outreach, a parallel summit where regional leaders are invited by the host to meet with BRICS presidents, after the Brazilian president had insisted on inviting Venezuela’s Juan Guaidó, whom none of the other BRICS countries recognize as president. The situation was privately criticized by diplomats from other BRICS member countries, given that their respective presidents would have liked to use the opportunity of meeting up with presidents from across Latin America – and yet, no president considered cancelling the trip halfway around the world. In the same way, frequent and growing geopolitical tensions between China and India trouble their bilateral relationship, but have not led to the group’s demise. Perhaps most importantly, in 2014 the grouping created the New Development Bank, and the bank is currently preparing to accept new members – most likely Uruguay, the United Arab Emirates and the Philippines – thus expanding its global footprint.

There are four reasons why calls for or predictions of the BRICS grouping’s demise are premature.

First of all, critics, especially in the West, tend to blow the differences between BRICS countries out of proportion or overlook what unites the five member countries. Commentators frequently point to profound differences between BRICS countries on issues such as U.N. Security Council reform, supported by India, Brazil and South Africa, but rejected by Russia and China. Yet few question the usefulness of the EU, NATO, or the G-7 despite equally frequent internal disagreements – Germany, for example, is part of the G-4 and supports reforming the U.N. Security Council, while Italy opposes the grouping. In the same way, there are numerous examples of democracies working with non-democracies being part of the same club – just think of NATO and Turkey, which saw its democracy flounder numerous times since becoming a member.

More importantly, most pundits overlook that, despite different political systems, economic characteristics, and geopolitical rivalries, the BRICS members share a profound skepticism of the U.S.-led international liberal order and the perceived danger unipolarity represents to their interests. This commitment often trumps other aspects often seen as more important from a Western perspective. The crisis in Venezuela offers a useful example: Despite Bolsonaro’s anti-socialist convictions and decision to no longer recognize Nicholas Maduro as president, the Brazilian government ended up siding with the Venezuelan dictator in rejecting the United States’ rhetoric about a potential military intervention, which, Latin American leaders feared, was setting a dangerous precedent. A similar dynamic became apparent in 2014, when the BRICS countries refused to criticize Russia’s President Vladimir Putin after the annexation of Crimea, widely seen as a flagrant violation of international law. Despite the BRICS countries’ strong commitment to non-intervention and the defense of sovereignty, they considered the United States’ forceful response – including sanctions and pressure on others to diplomatically isolate Russia – as a symbol of a unipolar order that the BRICS are seeking to overcome.

It was thus no coincidence that three of the five most prominent leaders who have so far chosen not to congratulate U.S. President-elect Joe Biden are BRICS members. While the governments of Brazil’s Bolsonaro and Russia’s Putin have not commented on the election at all, China’s Xi Jinping decided to delegate the task to Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin. Their reaction to Trump’s defeat is no coincidence. While the current U.S. president attacked the liberal international order the United States had helped create, and favored a world shaped by great powers and spheres of influence, Biden symbolizes, from the BRICS’ perspectives, a return to the pre-Trump world, as the recent article “Why America Must Lead Again“ in the magazine Foreign Affairs attests.

In addition, the economic rationale for keeping the BRICS grouping alive remains sound. Over the past two decades, trade and investment among the five member countries skyrocketed, even though it is still largely limited to each member countries’ ties to China. Given growing economic dependence across the grouping on Chinese demand and investment, voluntarily rejecting the possibility for cabinet members and hundreds of bureaucrats to engage their Chinese counterparts sounds implausible – particularly given that mutual knowledge among BRICS members, particularly between Brazil, South Africa, and the group’s Asian members, is still very limited.

BRICS meetings can also stabilize bilateral ties. For example, the yearly meetings between high-ranking government ministers and pre-scheduled facetime with Xi provided a welcome excuse for Bolsonaro to tone down his anti-China rhetoric and adopt a more pragmatic approach as the 11th BRICS Summit was approaching. In an increasingly China-centric world, actively dismantling the BRICS grouping would seem like a diplomatic own goal, particularly for South Africa and Brazil, who are still struggling to adapt to a post-Western world.

Finally, not only is the cost of BRICS membership limited, but the diplomatic benefits it generates remain significant. For Bolsonaro, for example, hosting Xi, Putin, India’s Narendra Modi and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa last year will stand out as the most important diplomatic event of his presidency, allowing him to look statesman-like. Particularly now that Bolsonaro faces growing diplomatic isolation in the West over Brazil’s environmental record, the BRICS serve as all-weather friends who would never openly criticize Brazil’s internal matters. In the same way, it is often forgotten that the BRICS allowed Putin to host pompous summits with numerous international leaders at a time when the West actively sought to isolate Russia’s president.

Even as the 12th BRICS Summit generated very little international visibility – in part because it took place virtually, and in part because it was eclipsed by other events such as the US elections – member countries are very unlikely to heed the often-voiced advice to dismantle the BRICS grouping.