To use a line of Lenin’s, which has been often referred to over the past year, as the world convulsed from the COVID-19 pandemic alongside serious upticks in geopolitical competition, some of which at times threatened to erupt into armed hostilities: “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” Replace “weeks” by “years,” and you have an accurate sense of the storm we have collectively weathered over the past 12 months.

Amid all the chaos of the year that went by, many new books published during this year of the plague tried to make sense of the past and the present, in many cases as ways to understand what the future may hold, as books often tend to. The five mentioned in what follows not only reached the reading public this year; they also explain many of the trends and patterns the year has seen emerging, for better or worse.

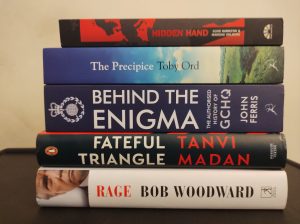

Bob Woodward, “Rage”

Arguably, 2020 was the year of U.S. President Donald Trump – but not for the good, either for him or the country he leads. On November 3, Trump was squarely defeated by Joe Biden in the U.S. presidential elections, following which he embarked on a campaign — simultaneously, conspiratorial, petulant and spectacularly quixotic — to have the results overthrown. But it was Trump’s denial and dillydallying when it came to the United States’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic that has come to haunt that country, where 326,242 people have died from the disease so far.

In Woodward’s new book – his second on the Trump administration – among other things, he takes us through how the Trump administration sought to make sense of the pandemic as news started trickling in from China about the novel coronavirus. Astonishingly, as Woodward makes it clear, the U.S. intelligence community and the National Security Council staff had made it crystal clear to Trump as early as late January about the severity of what would follow from the virus. And yet.

Tanvi Madan, “Fateful Triangle: How China Shaped US-India Relations During the Cold War”

New Delhi was one of the few capitals in the world that profitably dealt with the Trump administration, employing dollops of flattery to keep the India-U.S. relationship on steady course, most recently visible during Trump’s India trip in February. (Famously, early on in the Trump presidency, Indian Minister of External Affairs S. Jaishankar exhorted the world to “analyze” Trump instead of “demonizing” him.) But as many analysts note, what has helped the India-U.S. relationship keep a steady upward course independent of White House occupants is China. Plainly put, both countries, in their own ways, need each other to keep a check on Chinese ambitions. During the Ladakh standoff this year, which shows no signs of abating anytime soon, India and the U.S. have maintained close communication, with both sides possibly sharing intelligence. The Trump administration, to its credit, has also squarely counted India in as a front-line state in the fight against Chinese territorial revisionism.

But China was also a crucial (though far from being the only) variable that shaped the India-U.S. relationship during the Cold War. As two examples: India sought and received military aid from the United States during its 1962 war with China. The Special Frontier Force — an elite, secretive special operations force predominantly staffed by ethnic Tibetans — which was used by India in a military operation against China in Ladakh in August also has historic links with the U.S Central Intelligence Agency which helped train early volunteers to that force, originally called “Establishment 22.”

Brookings scholar Tanvi Madan’s deeply researched new book looks at the intertwined Cold War relationships between India, China and the United States. If past is indeed prologue, readers will be well served to peruse her book.

John Ferris, “Behind the Enigma: The Authorised History of GCHQ, Britain’s Secret Cyber-Intelligence Agency”

If 2016 saw one improbability (Trump’s election) cast a long shadow over the next four years, the British referendum to leave the European Union that year has built up to a denouement come January 1, when “Brexit” will fully come to force in terms of the United Kingdom’s separation from the EU single market and customs union. Even though a deal between the U.K. and the EU was struck on December 24 that will keep the U.K. and the EU tethered together, albeit in a limited sense, there is no escaping the feeling that January 1 will mark a turning point for the country and its strategic aspirations, for good or bad. As faithful viewers of “The Crown” will also attest, Brexit appears as culmination of a steady post-World War II decline of the once-great power, as the country careened from one crisis to the other, many of them its own making; such history is not for Britain optimists.

But in this season of English gloom, it is easy to forget that the country’s storied security establishment played a crucial role in the Cold War – and is likely to continue to do so in the future, should another one materialize on the horizon. One of them, the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) – the United Kingdom’s version of the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) – has played a crucial role in signals intelligence (SIGINT) and decryption efforts over decades. GCHQ is also one of the key nodes in the Five Eyes SIGINT gathering and sharing arrangement. Over the past year, the Five Eyes powers, which also includes Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States, have sought to play a greater collective role in managing strategic challenges emanating from China. It is not particularly presumptuous, thus, to assume that it has also directed considerable intel gathering capabilities towards that country. As Britain, having turned away from the European Union, looks to the Indo-Pacific, the GCHQ will assume added salience for the country and its regional allies.

In a new book – the latest “authorized” account of a British intelligence organization – historian John Ferris traces the history of the GCHQ, providing the reading public a valuable account of that secretive organization’s undertakings and role in British foreign policy.

Clive Hamilton and Mareike Ohlberg, “Hidden Hand: Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World”

That China executes interference and influence operations around the world through the United Front Work Department to further the interests of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is something that is now well known. Such covert operations — through a Byzantine system of intelligence agents, CCP members, the Chinese diaspora as well as witting and unwitting foreigners – burst into public consciousness in Australia a few years ago; in 2018 Australia passed three new national-security laws that sought to curb them. Over the past year, the United States has also sought to aggressively fight back Chinese interference, influence and other covert operations, often leveraging the 1932 Foreign Agents Registration Act. For example, the U.S. Justice Department has charged individuals in two separate cases, in September and October, under FARA, for illegally acting as Chinese agents in the U.S.

In a new book, Australian academic Clive Hamilton and German scholar Mareike Ohlberg offers a sweeping view of China’s efforts to penetrate Western political systems, academia, businesses and cultural institutions as part of its efforts to “reshape” the world in its own image through a variety of means. As China charts its post-pandemic path while key Western governments flounder, it is likely to double down on these efforts, seeing a decisive opening to consolidate its place as a great power. Hamilton and Ohlberg’s book is a good starting point for all who may want to know what such efforts could look like.

Toby Ord, “The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity”

But beyond geopolitics and strategic wrangling, this was the year when catastrophic risks hit home. As of December 24, 1,733,400 people globally have lost their lives in the COVID-19 pandemic. Just when some countries felt that they had the pandemic under control, a new strain of the novel coronavirus observed in the United Kingdom has added to fears that the end may still be some distance away.

But pandemics are one of the many risks that could prove to be an existential threat to humanity; climate change, technological disruptions as well as rare natural disasters – not to mention that perennial favorite, nuclear war — all lurk in the background as black swans. In a meticulously researched new book (with 170 pages of endnotes and bibliographical references), Oxford academic Toby Ord surveys various doomsday scenarios to reach an extremely bleak conclusion: humanity’s odds of surviving the next 100 years is one out of six.