President Lobsang Sangay, who heads the Tibetan government-in-exile, says his intense shuttle diplomacy with American leaders over the past year has led to a series of victories for Tibet’s embattled monks and monasteries, Buddhist pilgrims, and pacifist protesters.

Sangay explains in an interview that his recent breakthrough meetings at the White House, and with a bipartisan coalition of leaders on Capitol Hill, might ultimately help halt the waves of killings that Chinese armed forces have carried out over the past half-century to crush calls for religious and political freedom in Tibet.

China’s serial use of lethal force against unarmed protesters across the Tibetan Plateau has been documented in detail by the U.N.’s Committee against Torture. Sangay says his allies in the U.S. government could potentially stop these atrocities by imposing Global Magnitsky Act sanctions on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders found responsible for ordering troops to open fire on Buddhist dissidents.

The Harvard-educated Sangay has spent 2020 shuttling between Washington D.C. and Dharamsala, the ever-expanding sanctuary India’s government has provided for the Dalai Lama and tens of thousands of exiled Tibetans, to formulate a common strategy on reaching that goal.

During a whirlwind of talks over the past weeks, he says, “I have met White House officials and staff members from both the President’s and the Vice President’s Office.”

Buddhist leaders and worshippers across the Himalayas are likely to celebrate his groundbreaking invitation to the White House because it “represents hope for the Tibetans and is also a mark of solidarity of the White House with Tibetans in Tibet and the Tibet cause.”

Just before that meeting, the U.S. State Department issued an official determination that: “In gross violation of the principles set forth in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the CCP maintains a military occupation of Tibet that dates to the 1950s.”

That means, Sangay says, the U.S. government has officially acknowledged that Tibet was independent before People’s Liberation Army troops marched into the Buddhist kingdom in 1950.

The explosion of support for Tibet across the American political arena has even included one call in the House of Representatives for the United States to affirm Tibet’s independence. With his proposed Free Tibet Act of 2020, Congressman Scott Perry seeks “To authorize the President to recognize the Tibet Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China as a separate, independent country.”

In a follow-up missive he dispatched in mid-December, Perry urged the White House to censure “more than 70 years of uninterrupted, illegal occupation of Tibet by the People’s Republic of China.”

Decades of communist rule have devastated Tibet, Sangay says. Before being elected president in a democratic vote by Tibetan exiles who have found sanctuary across the continents, Sangay was an international law scholar at prestigious Harvard Law School, where he focused on Tibet’s blood-soaked history following the Chinese invasion.

“The Tibetan government-in-exile estimates that a total of 1.2 million Tibetans have died as a result of the Communist Chinese occupation,” he wrote in one study for Harvard Asia Quarterly.

“This is a remarkably high number considering the size of the Tibetan population is currently only roughly six million.”

These million-plus Tibetan casualties were calculated based on interviews with refugees who managed to escape – across the planet’s highest mountains and past armed Chinese sentries – to India or Nepal, and based on official documents smuggled out of Tibet.

“The breakdown of specific death counts,” he says, includes 173,221 Tibetans who have died in prisons and labor camps, 156,758 who have been executed, 342,970 who starved as occupying Chinese soldiers seized ever-greater shares of Tibetan crops, 432,705 Tibetans who lost their lives trying to ward off the Chinese invasion or joining popular uprisings against Communist rule, and 92,731 more who died via torture.

During China’s “illegal occupation,” he says in the interview, “Tibetans have been deprived of their language, religious, and environmental rights, and basic human rights, and the situation in Tibet has gone from bad to worse.”

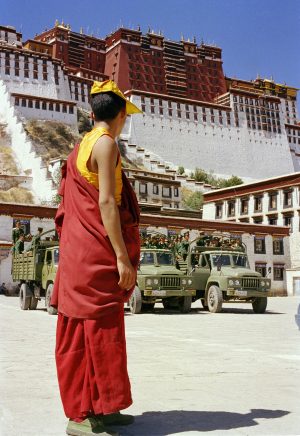

A Tibetan monk outside the Jokhang Temple, one of the holiest sites in Tibetan Buddhism and site of sporadic demonstrations against Communist rule that are crushed by the Chinese military. Photo by Kevin Holden.

Despite Chinese campaigns aimed at crushing Tibet’s spiritual and cultural foundations, the government-in-exile is not seeking to regain Tibet’s full independence. Instead, Sangay has been canvassing U.S. government support for the Dalai Lama’s proposal to transform Tibet into a “zone of peace” between the great powers of China and India.

On awarding the Dalai Lama the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, the Norwegian Nobel Committee lauded his Five-Point Peace Plan for Tibet, which envisions the “restoration of fundamental human rights and democratic freedoms and the abandonment of China’s use of Tibet for nuclear weapons production.”

Since becoming president, Sangay has amplified the Dalai Lama’s calls to create a self-governing democratic Tibet, in association with the People’s Republic of China, accompanied by the withdrawal of PLA troops.

Yet China continues to deploy PLA forces, including People’s Armed Police armed with automatic weapons, to suppress peaceful protests across Tibet, according to evidence presented to the 10 independent experts who comprise the U.N.’s Committee against Torture, which monitors compliance with the Convention against Torture.

Just months after the PLA’s armed attacks on Buddhist acolytes staging anti-government marches in the Tibetan capital in March of 2008, these U.N. experts notified the Chinese government it was obligated, under the Convention, to punish those deploying deadly force “against peaceful demonstrators and notably monks” in Lhasa and other parts of Tibet.

China’s leadership, they added, must “conduct investigations or inquests into the deaths, including deaths in custody, of persons killed in the March 2008 events in the Tibetan Autonomous Region.”

Although China signed the Convention in 1988, its leaders have steadfastly failed to comply with the treaty, says Felice Gaer, who until last year was vice chair of the Committee against Torture. Instead, she recounted in a law journal article, the Chinese government responded to one U.N. communique “by promptly attacking the Committee’s country rapporteurs as politically biased” and characterized their outlining of treaty violations as “slanders.”

Gaer says in an interview that after she and her colleagues on the U.N. Committee questioned Chinese officials about the killing of Lhasa protesters in 2008, they presented further allegations on the ongoing misuse of deadly firepower against demonstrators, including “the indiscriminate firing by the police into crowds,” in Tibet in 2010, in 2011, in five separate incidents in 2012, and again in 2014, and demanded explanations from Chinese authorities.

China has a standing duty to investigate and, as the evidence warrants, prosecute security forces who carried out extrajudicial killings, says Gaer, an internationally renowned scholar on U.N. law and religious freedom who now heads the Jacob Blaustein Institute for the Advancement of Human Rights.

While the U.N. currently has no enforcement mechanisms to halt China’s violations of the pact, Sangay says the United States can use its Global Magnitsky sanctions regime as an alternative deterrent.

Imposing penalties on CCP leaders who command soldiers to shoot unarmed protesters, he says, might prevent other party officials from taking similar actions in the future.

Sangay hailed the passage, just days ago, of the Tibet Policy and Support Act, which calls for Magnitsky penalties against CCP officials attacking Tibet’s Buddhist leaders.

He likewise praised Congressman Chris Smith, the human rights champion who co-sponsored the legislation, for his longstanding opposition to Chinese assaults on Tibet’s monasteries.

The new Tibet Act, Smith says in an e-mail interview, opens the way for stepped-up contacts with President Sangay and members of Tibet’s parliament-in-exile, and for penalizing the architects of religious repression in Tibet.

The act, embedded in a massive government spending and pandemic relief package that President Donald Trump signed on December 27, is a clarion warning to the Chinese Communist Party that assaults on Tibetan Buddhism will be swiftly met with American sanctions, says Congressman Smith.

Will Congress press for sanctions against Chinese rulers who have overseen the slaughter of Tibetan protesters, political prisoners, and Buddhist youths seeking freedom beyond the tightly guarded borders?

“There are grave and justified concerns about the human rights situation in Tibet – and wide bipartisan support for direct personal sanctions that will hold Chinese officials accountable for human rights abuses,” says Smith, a senior member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee and co-leader of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China.

Smith, who helped create that commission’s Political Prisoner Database tracking Tibetan lamas who have been jailed (or, in the case of the Panchen Lama, kidnapped by government agents as a child), adds: “Given the large-scale, arbitrary detentions of Tibetans and efforts to eviscerate Tibetan Buddhism – including through signaling that atheist Communist officials will pick the Dalai Lama’s successor – targeted Global Magnitsky sanctions are appropriate and should be employed.”

One of Congress’s outstanding crusaders for universal freedoms, Smith has been the target of repeated offensives launched by the Chinese leadership. Last summer, after Washington slapped sanctions on a CCP Politburo leader who helped transform Tibet into a high-tech police state, Beijing brandished “counter-sanctions” against Smith and other prominent rights guardians including Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, and Sam Brownback, the U.S. State Department’s Ambassador for Religious Freedom.

A decade ago, congressional cyber sentries discovered Chinese government hackers had invaded Smith’s computers, searching for information about Beijing’s violations of rights accords and about his proposed Global Online Freedom Act.

Beijing’s escalating, intercontinental attacks on rights guardians around the world, and the build-up of its armies of secret police across Tibet, Xinjiang, and now Hong Kong, all show “China has become a global threat to universal values and global democratic norms,” says Sangay.

At the same time, Sangay extols Joe Biden’s promised shield for Tibetans, with the president-elect’s pledge that he “will sanction Chinese officials responsible for human rights abuses in Tibet.”

Penalties should be aimed at those committing rights crimes that have already been chronicled by U.N. scholars, including the torture of nuns and monks in Tibet’s notorious prisons. Sanctions that hold accountable “leaders perpetrating gross human rights violations,” Sangay says, “also send a strong message that their actions will not go unnoticed and unanswered irrespective of where they are.”

Tsering Tsomo, who heads the Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy, says she is now preparing a list of potential targets for Magnitsky penalties for the U.S. State Department.

Tsomo and other scholars at the center, located in Dharamsala, near the western edge of the Tibetan Plateau, have long been at the forefront in chronicling rights crimes committed by Communist rulers across the plateau. They have interviewed Buddhist novitiates tortured with electric truncheons in Tibetan jails, along with witnesses to blood-drenched crackdowns on popular calls for change.

Channeling their evidence to the U.N., they have also collaborated with whistle-blowers inside Tibet who smuggled out a classified government report compiled for the Chinese leadership that outlined the army’s use of machine guns and armored personnel carriers to crush demonstrations in Lhasa in March of 2008.

China’s repeated armed assaults on civilians, and routine torment of political detainees, are part of longstanding, widespread, and systematic attacks on Tibetan society, and constitute “crimes against humanity” under international law, Tsomo says. Democracies across the West that have adopted Magnitsky sanctions regimes, including the U.S., the U.K., and now the EU, should all use these laws to punish the worst perpetrators of rights crimes across the Chinese leadership, she says.

John Gaudette, a rights lawyer who helped the Tibetan Center prepare a series of reports for the Committee against Torture, says Magnitsky measures should be aimed not just at CCP officials, but also at PLA officers deploying deadly weapons against dissidents or asylum seekers.

Spanish rights activist Alan Cantos, who heads the pro-Tibet support group Comité de Apoyo al Tíbet, says more powerful arsenals of legal tools are emerging across Europe that can be used to combat China’s crimes against humanity.

While Magnitsky regimes provide for visa bans and freezes on financial assets for rights violators, a constellation of progressive courts has begun exercising “universal jurisdiction” to conduct Nuremberg-style trials for those committing heinous crimes like genocide and state-organized torture of religious detainees.

Cantos teamed up with José Elias Esteve Moltó, a professor of international law at the University of Valencia, to file a history-making suit on behalf of Tibetan victims of Chinese rights crimes in Spain’s National Court nearly a decade ago.

Yet as these criminal proceedings progressed, with one judge issuing international warrants for the arrest of former Chinese President Jiang Zemin and Premier Li Peng, Beijing exerted tremendous pressure on Madrid to halt the case.

The Spanish parliament ultimately surrendered by freezing the lawsuit, but Cantos says the case might still be revived. An “appeal we filed at the European Court of Human Rights is pending resolution,” he says.

With a changing of the guard in Madrid’s corridors of power, he says, “The Socialist government in Spain would definitely be more inclined to resurrect our universal jurisdiction law.”

“In fact,” he adds, “there is a draft for a new even more progressive and expansive law than the one that was crushed due to Chinese pressure.”

Cantos and Sangay were both invited to join a virtual roundtable that covered future prospects for a Nuremberg-like trial of Tibet’s oppressors that was staged by the head of the U.S. Mission to the United Nations in Geneva in early December – yet more evidence of growing U.S. support for the cause.

Kevin Holden is a freelance journalist based in Asia.