The Chinese Communist regime, often with the aid of other governments, is systematically hunting down its political and religious exiles, no matter where in the world they seek refuge.

In cases that occurred or have come to light just since December, Nepali police detained five Tibetans when they attempted to discreetly participate in elections for Tibet’s government-in-exile in India. A Chinese-Swedish businessman with ties to the Falun Gong spiritual group was stopped in Poland based on an Interpol red notice, held for 20 months, and threatened with extradition to China. Uyghur doctor Gulshan Abbas was arbitrarily sentenced to 20 years in prison in China, in apparent retribution for her sister speaking publicly in the United States about the human rights crisis in Xinjiang. And Hong Kong democracy activists and former legislators were named on the Hong Kong police’s “wanted list” under the new National Security Law, despite residing in Europe, Taiwan, and the United States.

Beijing is not alone in these pursuits. A new report published on February 4 by Freedom House – “Out of Sight, Not Out of Reach” – documents the many ways in which people who flee repression at home are still subject to attacks – including detention and physical violence – while abroad, even after they reach democratic countries.

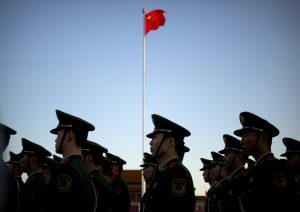

Nonetheless, among the 31 origin governments found to have engaged in transnational repression since 2014, China’s authoritarian regime is conducting the most sophisticated and comprehensive campaign of its kind. The sheer breadth and global scale of the effort is unparalleled. Freedom House’s conservative catalogue of direct, physical attacks during the coverage period includes 214 cases traced to China, far more than any other country and accounting for more than one-third of the total 608 incidents documented worldwide.

These egregious and high-profile cases are only the tip of an iceberg, arising from a much larger system of surveillance, harassment, and intimidation that leaves many in the Chinese exile and diaspora communities with the feeling that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is watching them and constraining their ability to exercise basic rights, even when they are living in a foreign democracy. All told, these tactics affect millions of people in at least 36 host countries across every inhabited continent.

The Targets

The extensive scope of Beijing’s transnational repression is the result of a broad and ever-expanding definition of who should be subject to the CCP’s extraterritorial control. The campaign has certainly pursued political dissidents, human rights activists, and journalists living abroad or attempting to avoid persecution in China by residing in neighboring countries like Myanmar or Thailand.

But the CCP also targets entire ethnic and religious groups, including Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Falun Gong practitioners, who together number in the hundreds of thousands globally. Among other cases, the report documents the mass deportation of more than 100 Uyghurs from Egypt and Thailand to China; an ethnic Tibetan police officer in New York who was reportedly recruited to spy on exiles; and harassment or physical assaults by members of visiting Chinese delegations or pro-Beijing proxies against peaceful Falun Gong protesters in the United States, the Czech Republic, Taiwan, and Argentina.

Since CCP leader Xi Jinping launched an aggressive anti-corruption campaign in 2012, the party’s disciplinary apparatus has sought out what may be thousands of former regime officials who are living abroad and accused of malfeasance. And over the past year alone, the list of targeted populations has also come to include ethnic Mongolians and Hong Kongers. In September 2020, for example, a man from China’s Inner Mongolia region who was living in Australia on a temporary visa reported that he had received a call from local authorities in China warning him that if he spoke out about protests in the region and corresponding repression, including on social media, then he would “be withdrawn from Australia.”

The Chinese government has even sought to assert control over foreign nationals with no direct ties to the People’s Republic – including Taiwanese citizens and ethnic Chinese citizens of other countries – who are critical of CCP influence and human rights abuses.

The Tactics

The CCP’s transnational repression campaign spans the full spectrum of tactics: direct attacks like renditions and beatings, co-optation of other countries’ authorities to detain and render exiles, passport suspensions and other mobility controls, and long-distance threats like online intimidation, spyware, and coercion by proxy using family members still in China.

Notably, the parts of the Chinese party-state apparatus involved in transnational repression are as diverse as the targets of the campaign. The harshest forms of transnational repression by Chinese agents – espionage, cyberattacks, threats, and physical assaults – emanate primarily from the CCP’s domestic security and military services, with their various international branches. Other forms of intimidation are undertaken by Chinese diplomats or officials in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs bureaucracy.

Three additional aspects of Beijing’s campaign stand out from the efforts of most other authoritarian regimes.

First, the Chinese regime has significant technological prowess, which it brings to bear in the form of sophisticated hacking and phishing attacks. One of its newest avenues for such activity has been WeChat, a messaging, social media, and financial services app that is ubiquitous among Chinese users around the world, and through which the party-state can monitor and control discussion in the diaspora.

Second, Beijing’s overt transnational repression efforts are embedded in a broader framework of influence that encompasses cultural associations, diaspora groups, and in some cases organized crime networks, placing the regime in contact with a huge population of Chinese citizens, ethnic Chinese diaspora members, and minority populations from China who reside around the world. A network of such proxy entities – like “anti-cult” associations in the United States, Chinese student groups in Canada, and pro-Beijing activists with organized crime links in Taiwan – have been involved in harassment and even physical attacks against party critics and religious or ethnic minority members. The increased distance from official Chinese government agencies offers the regime plausible deniability while accomplishing the goal of sowing fear and encouraging self-censorship beyond China’s shores.

Third, China’s geopolitical and economic clout allows it to assert unmatched influence over countries near and far. The CCP does not hesitate to use this leverage to silence dissent overseas. Since 2014, Beijing has convinced governments in countries as diverse as India, Thailand, Serbia, Malaysia, Egypt, Kazakhstan, the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, and Nepal to detain – and in some cases deport to China – CCP critics, members of targeted ethnic or religious minorities, and refugees. From this perspective, the regime’s use of transnational repression poses a long-term threat to the rule of law in other countries. Beijing’s influence is powerful enough not only to violate the rule of law in an individual case, but also to reshape legal systems and international norms in its interests.

Looking Ahead

Extending the party’s grip on exile and diaspora communities is a clear priority for Xi Jinping and the top echelons of the regime’s security apparatus. While it has become more difficult for foreign governments to pressure Chinese leaders to improve their human rights record at home, all countries – and especially democracies – have an interest in resisting requests from Beijing that would threaten the rights of expatriate Chinese, ethnic minorities from China, and religious believers within their own borders. In fact, it would behoove host governments to take proactive measures to protect these targets of transnational repression.

Besides the humanitarian, moral, and sometimes legal obligations to take such protective action, governments have a responsibility to combat practices that could easily be extended to their own citizens. The CCP has repeatedly demonstrated its will and ability to make this leap in other areas, such as the media sphere. Protecting these vulnerable communities from the CCP’s long arm of repression today will serve to protect the full array of a host country’s people, sovereignty, and democratic institutions tomorrow.

Nate Schenkkan is director for special research at Freedom House and primary author of “Out of Sight, Not Out of Reach.”

Sarah Cook is research director for China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan at Freedom House.