The United Nations’ latest multilateral treaty outlawing nuclear weapons became international law last month after being ratified by 52 countries. But noticeably absent was Japan, a country that has built a niche reputation around post-war nuclear nonproliferation.

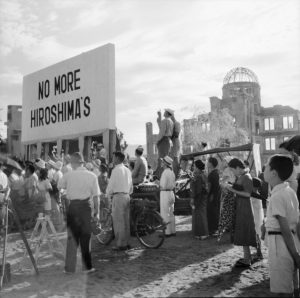

As the only country to actually be attacked by nuclear weapons in war, Japan’s failure to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) attracted criticism from numerous pro-disarmament groups and atomic bomb survivors, who said the decision discredits the government’s long-standing anti-nuclear position.

The TPNW is the first binding treaty that defines nuclear weapons as illegal and prohibits almost all nuclear weapons activities: developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, acquiring, possessing, and stockpiling nuclear weapons. A landmark feature of the TPNW is the acknowledgement of the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons and their continuing existential threat to humanity. It also incorporates victim assistance and environmental compensation in recognition of the devastating effects of nuclear weapons use and testing.

The TPNW is seen as a step up from the 1970 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which aims to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and materials for its production. The NPT essentially allows its five nuclear state members – China, France, Russia, the United States, and the United Kingdom – to legally possess nuclear weapons. Japan joined the NPT in 1976 and since then it has gained recognition for actively promoting the importance of international cooperation for a nuclear-free world.

However, all nine de facto nuclear weapon states (including India, Israel, North Korea, and Pakistan) have refused to sign the TPNW. So have most U.S. allies, from NATO members such as Canada, Germany, Spain, and Turkey to allies in the Pacific – including Japan.

In January Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide reiterated that Japan, which remains under the U.S. “nuclear umbrella,” has “no intention of signing the treaty” due to the lack of support by nuclear armed states and non-nuclear states. Japan has expressed support for the goals behind the TPNW but with only 52 states ratifying the treaty out of 193 U.N members, Defense Minister Kishi Nobuo expressed doubts over the treaty’s effectiveness.

Japan is caught between being a nuclear umbrella state while also being the only country to have suffered from nuclear weapons. In 2013 at a U.N. General Assembly meeting on nuclear disarmament then-Prime Minister Abe Shinzo boasted that the elimination of nuclear weapons has been “the Japanese people’s unwavering aspiration since World War II.” But a widening gap between public opinion and the government’s official position prompted an atomic bomb victim organization to launch a petition in December in favor of joining the U.N. treaty which collected over 13 million signatures. Meanwhile, a public opinion poll conducted in August 2019 revealed that 75 percent of the Japanese public support the ban treaty.

The U.N. says global nuclear disarmament is a top priority yet a nuclear free world remains a distant dream. Japan must contend with the possibility of escalating conflict with neighboring North Korea, China, and potentially Russia and its defense depends on extended nuclear deterrence via the U.S.-Japan security alliance.

Tanaka Shingo, an associate professor of international relations at Osaka University, says it isn’t wise for Japan to take part in the TPNW amid growing regional tensions and recommends a gradual and realistic approach. “From a national interest perspective radical nuclear disarmament would create serious consequences. Japan should put off joining the TPNW as it could be used as leverage,” Tanaka said.

“But from a humanitarian stance I can see how it could also be contradictory.”

Akiyama Nobumasa, a nuclear security policy professor at Hitotsubashi University, is pessimistic about the prospect of nuclear weapon states and nuclear armed states joining the TPNW in the near future. While he acknowledges that a ban treaty is a good platform to strengthen social norms around nuclear non-use, nuclear armed states are caught in a deadlock that is very difficult to solve.

“Japanese membership to the TPNW itself is not the goal. We have to expect something substantial for Japan to join the TPNW in terms of reducing nuclear weapon held by North Korea, China, and the United States,” he said.

Last year marked the 75th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings as well as the 50th year since the NPT came into effect. Japan has made consistent efforts toward eliminating nuclear weapons but developing concrete measures to advance disarmament and nonproliferation through consensus has stalled. Akiyama argues the TPNW does not address the full story behind nuclear possession.

“Joining the ban treaty is like trying to achieve perfection. But by signing this treaty, how are we going to achieve the goal of pressuring nuclear states to give up nuclear weapons? The humanitarian element is only part of it. The national security context for every country is different and the TPNW approach to banning weapons altogether is a catch-all discourse,” he said.

Akiyama says that some people see the abolition of nuclear weapons as Japan’s natural manifesto or destiny. On the other hand, Japan’s deadly experience with nuclear weapons is an example of why some nuclear armed states justify the need for nuclear deterrence. “The solution lies in convincing these states to give up nuclear weapons, but we need to understand more thoroughly where the problems are. We cannot improve security dynamics without listening to nuclear armed states.”

A U.N. NPT review is planned for August this year, in which nuclear states such as China, Russia and the U.S will hold talks with non-nuclear states. However a rift at the previous meeting in 2015 prevented the adoption of a consensus document. Akiyama emphasizes that discussing ways to reduce a heavy security reliance on nuclear weapons is key and “reducing the risk of catastrophe is the responsibility of all states that possess nuclear weapons.”