Every time I see the deep, round scars on her wrists and arms, I think of the blood flowing out of the holes that made them, dripping onto the floor of that grim torture room in the Ghulja city police station, as she is tortured to confess to crimes that do not exist. She is Saliha, my sister, one of thousands of youths in Ghulja whose lives turned into a nightmare after the Ghulja massacre.

On February 5, 1997, now 24 years ago, Uyghur demonstrators in Ghulja took part in a non-violent protest calling for an end to religious repression and ethnic discrimination in the city. After violently suppressing the demonstration, Chinese authorities arbitrarily detained large numbers of Uyghurs. Human rights organizations documented a pattern of torture in detention and unfair trials of detained Uyghurs. For their alleged role in the events, several Uyghur participants were executed.

Eight months after the massacre, the hunt for Uyghur youths with any connections to the February protest was still in effect. In October 1997, my sister Saliha, only 23 years old at the time, my niece Saide, 20, and a few other girls were coming home from a wedding in nearby Nilka, still resplendent in wedding finery and boisterous with laughter and jokes. The joy was not to last; for my sister, a nightmare spanning decades was about to begin. Five fully armed policemen burst into our home to arrest these girls. My father asked them to allow Saliha to rest for a moment at least, but to no avail. The policemen shackled her, forced her into a police car, and drove away as if she were wanted for murder. My mother fainted, my father stood motionless, and the rest of the family sunk into a horrified chaos, helpless.

They arrived at the Ghulja city police station, about six kilometers from Kepekyuz, where Saliha resided. She was ripped from the car and pushed into an interrogation room on the second floor of the police station. The questions began politely: Do you know Tursun Seley and his wife? Did you help his wife? Have you hidden her? We knew that you are friends.

Saliha answered firmly: No. I don’t know them; I didn’t see them; I don’t have any connections with them.

Their tone and interrogation methods intensified, and the policemen became impatient. First, they hit Saliha with a large club, starting from her back then all over her body. The most painful hit was to the back of her ears; her earrings broke into pieces, the stones thrown out of their sockets and clicking against cement. She didn’t know for how long the questioning and beatings continued. As time went by with no results, they handcuffed her with shackles that had nails protruding from the inside. When the policemen pressed against the sides of the handcuffs, the nails dug into her skin and blood gushed out of her wrists. Slowly, she started losing feeling. The policemen continued squeezing blood from her, but again with no results. Soon, they brought out heavy leg shackles and bound her legs, then moved her to a corner between the first and second floor stairway. There, they attached her nail-handcuffs to a pipe that ran across the wall. Chinese police personnel who walked by would see her standing there, bleeding. It was evening, but it was impossible to sleep despite the pain and fatigue; she could hear the horrific screams of people coming out from similar “interrogation rooms.” To her, the whole building was a dark and deathly torture chamber.

She spent one month there, and to this day has not described everything that happened to her. She was released after a Chinese police chief was given a sizable bribe. We signed an agreement that Saliha was to stay within a six-kilometer radius of her house and be mindful that she was under watch 24/7. In effect, she was under house arrest.

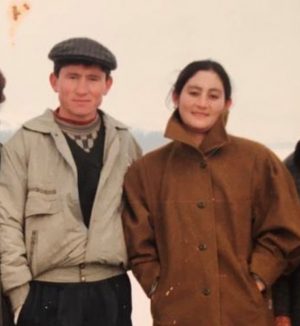

In July 1998, I went to Ghulja from my new home in Australia. It was three months after my nephew Hemmat Muhammat was killed by Chinese forces and nine months after Saliha’s release from detention. The purpose of the trip was to mourn for Hemmat’s death, but what I witnessed and experienced there was much worse. The most devastating experience for me was realizing my sister Saliha had changed drastically. The hilarious, radiant girl who loved to sing and dance and express herself was silent, muted. She had lost all faith in humanity. The same thing happened to my niece Saide. It happened to Patime, who was a friend of Saliha’s, my cousin Abdumennan, and so many others in our neighborhood who had been detained. Something inside them had broken after going through those brutal detentions. It seemed clear to everyone: We had to leave this place if possible and help the people here from abroad.

I left Ghulja in August of 1998. I tried my best to bring over any of my relatives. Saliha came to Australia in September 1999. It took her over 20 years to recount some of the horrific experiences inside China’s brutal torture chambers. That was one month of torture and questioning. Saliha misses our homeland and her childhood, but recoils at the idea of going back. The dark chamber continues to haunt her.

When Saliha and I heard our other sister Mesture and her family were sent to concentration camps in Ghulja in 2016, we were horrified; Saliha in particular became ill upon hearing the news. The terms “taken away,” “arrested,” or “detained” all equate to termination for us.

China is doing its best to prevent the world from seeing the Uyghur genocide and claim Uyghurs abroad are “lying.” Credible accounts from survivors are “fake news” and even a “Western conspiracy.” China claims that America is “jealous” of China’s rise as a world leader, so the United States is using the Uyghur genocide card to “wage war” against China. Sure, America may not wish to be replaced in its role on the international stage, but this argument does nothing to disprove China’s brutal genocide of the people it claims to be its own citizens.

We may not be seeing Uyghurs locked into gas chambers and gassed to death, or killed with weapons of mass destruction, but we are witnessing people being tortured, brainwashed, locked up by the millions, held as slaves, or having their organs harvested. Women are being raped and forced into unwanted marriages, or sterilized by force and used for experimentation in Chinese medical laboratories. In this century, these cruelties should not be a precursor to a government becoming more powerful on the world stage, no matter what sort of economic and political “benefits” China offers the world as a result. There is no acceptable condition where world actors can turn a blind eye to genocide.

Twenty-four years after the Ghulja massacre, there has been no accountability for the atrocities committed that day or the months after. In fact, China continues to hunt down every Uyghur who had a connection to that youth movement from the ‘90s and is punishing them by sending them to concentration camps. The survivors of the Ghulja massacre, the July 5, 2009 Urumqi protest, and the state violence of Alaqagha (May 2014), Hanerik (June 2013), Seriqbuya (April 2013), and Elishku (July 2014) make up a part of the millions of people detained in Chinese concentration camps since 2016. These and countless other unreported instances of oppression serve as testimony to the fact that, step by step, China will systematically erode our people from the earth, mentally, spiritually, culturally, and physically.

I had tears of satisfaction in my eyes when I heard the United States had recognized the genocide of the Uyghurs. It has given some hope to women who have suffered, like Saliha, and a will to keep fighting for the rights that have been taken away from us for so long. If the world ignores what China is doing in East Turkestan, we are giving tacit approval to genocidal governments and may witness the same atrocities elsewhere. It is time to urge other governments to join the U.S. and recognize the genocide of the Uyghurs. In particular, those brave women who survived China’s atrocities – like Saliha, Mihrigul Tursun, Tursinay Ziyawdun, Gulbahar Jelilova, Gulbahar Hatiwaji, Zumret Dawut, Rukiya Perhat, Sayragul Sautbay, Kalbinur Sidik, and many more unknown Uyghur and Kazakh women – need to be supported and believed. Their stories are weapons in the struggle against state brutality. By listening to them, we have the power to stop the atrocities in East Turkestan and everywhere else in the world.

Zubayra Shamseden is Chinese Outreach Coordinator at the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), a documentation and advocacy group based in Washington, D.C.