During the Trump presidency, the relationship between the United States and China spiraled into such a fierce rivalry that some pundits began talking of a new Cold War between the two powers. Before President Joe Biden took office as Donald Trump’s successor, there were some views that he would move to restore the U.S. relationship with Beijing. In his first foreign policy speech on February 4, however, he called China the United States’ “most serious competitor,” making it clear that he would inherit from Trump a tough stance against Beijing.

Arguably, no bilateral relationship receives as much attention as the U.S.-China relationship. An enormous number of monographs, essays, and editorials dealing with the confrontation between the two countries have been published. Few of these, however, look back on the history of World War II, when the United States was willing to treat China as a great power.

Before World War II, China, plagued by the unequal treaty system established in the wake of the First Opium War, was not yet globally recognized as a fully sovereign nation. The United States was one of the countries that enjoyed special privileges in China under this system. During World War II, however, the United States sought to give China international status not only as a full sovereign country but also as a great power. The U.S. endeavor succeeded, enabling China, along with the U.S., Britain, the Soviet Union, and France, to obtain a permanent seat at the U.N. Security Council.

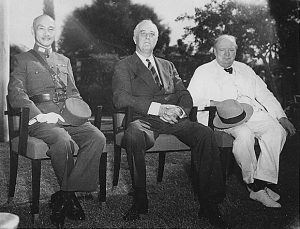

Among American officials, it was President Franklin D. Roosevelt who was particularly keen on promoting China’s international status. If he were the U.S. president today, how would Roosevelt deal with China? Would he still seek to make it a major U.S. partner, as he did during World War II?

It must be noted that Roosevelt wanted China to fulfill certain conditions as a great power. The first was the adoption of the so-called good neighbor diplomacy, which Roosevelt developed vis-a-vis Latin American countries in the 1930s. Due to repeated U.S. military interventions since the beginning of the 20th century, Latin American countries were decidedly hostile toward Washington. Roosevelt’s good neighbor diplomacy greatly alleviated their feelings by denying the possibility of military intervention and, for example, contributed to the establishment of a joint defense regime with them against the threat of Nazi Germany.

From this experience, Roosevelt regarded the model of good neighbor diplomacy as one that other countries, especially other great powers, should adopt. At the Tehran Conference in 1943, Roosevelt recommended it directly to Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin as a “policy for strong powers paramount in their regions,” such as the U.S. in the New World and the Soviet Union in Eastern and Northern Europe. Reflecting this emphasis on good neighbor diplomacy, the preamble of the U.N. Charter stipulates that “[w]e the peoples of the United Nations determined … to practice tolerance and live together in peace with one another as good neighbors.”

Roosevelt’s second condition was China’s acceptance of the U.S. military presence in Asia. According to Roosevelt’s post-war vision, China was to be responsible mainly for Asian stability and peace; Roosevelt did not, however, want China to become predominant in Asia. In January 1944, he approved a post-war military base plan proposed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS570/2), under which the U.S. would acquire dozens of bases in the region extending from the Kuril Islands to Southeast Asia.

Roosevelt’s third and last condition was the unification of China, which was then divided between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party. In order to help the two parties accommodate, Roosevelt dispatched Patrick J. Hurley, a former secretary of war of the Hoover administration, as his special envoy to China in the summer of 1944. After Hurley gave up mediation efforts in November 1945, Harry S. Truman, Roosevelt’s successor, sent George C. Marshall to China for the same purpose.

Despite Marshall’s endeavors, however, a civil war erupted between the two parties in 1946, leading China into a situation where it could not meet the third condition. Three years later, the Chinese communists won the civil war, and established a unified government in Beijing. From the U.S. perspective, this was not a China that could meet either the first or second of FDR’s conditions.

After reaching an accommodation with Beijing in 1972, the United States developed the so-called engagement policy, and in the words of the Trump administration, expected China to become “a constructive and responsible global stakeholder.” However, the engagement policy did not work as Washington expected. As China has grown economically and militarily, its international behavior has become contradictory to both the first and second conditions originally laid down by Roosevelt. From this observation, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that even FDR, where he alive today, would take a tough stance against Beijing.

Since the Chinese Communist Party won the civil war, the United States has found Japan to be its nearly perfect partner in Asia. Japan has maintained its domestic stability, and has been willing to accept a U.S. military presence in Asia. Despite its enormous power, Japan has developed a restrained diplomacy that can be called good neighbor diplomacy. Ironically, Roosevelt’s vision of making China a post-war great power implies that, unless China changes its international behavior, there would be little possibility of the United States abolishing its Japan-centered East Asia policy, and pursuing a bipolar condominium with China.

Keikichi Takahashi is an associate professor at Osaka University in Japan, specializing in U.S. diplomacy toward East Asia. He is the author of a Japanese-language book titled “China or Japan? The American Search for a Partner in East Asia, 1941-1954.”