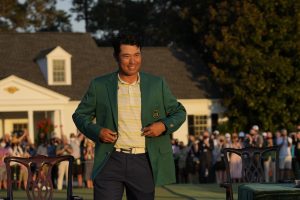

On April 11, the final Sunday of the 2021 Masters Golf Tournament, Hideki Matsuyama shot 10 under par at Augusta National Golf Course to win his first green jacket. The Masters Tournament boasts one of the largest purses, prides itself as being one of the most exclusively attended golf competitions, and invites the most international field of players of any golf competition. Beyond the monumental achievement of winning this famous invitational, Matsuyama also made history in becoming the first Japanese man to win a major tournament. He follows in the footsteps of Vijay Singh, from Fiji, the first Asian man to win the Masters in 2000.

Japan’s known love for the game of golf manifested in its reaction to Matsuyama’s victory. Japan has an estimated 2,500 courses — more than the rest of Asia combined — and is known for its multi-story driving ranges. Japanese audiences took to the internet to express their joy, uniting other Japanese and international fans in a shared moment of celebration amidst ongoing global COVID-19 restrictions. Matsuyama’s caddie, Shota Hayafuji, also shot to viral stardom after he removed his cap and bowed to the course after replacing the pin on the 18th green. Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide deemed the performance an “amazing feat.” These immediate celebrations may take years to translate to on-the-course success for other Japanese golfers, contributing to the growth of golf in Japan.

The impact of individual role models for sport in Asian societies has been seen many times over. The closest possible prediction of Matsuyama’s potential impact is the astonishingly quick development of South Korean women golfers. Se-ri Pak joined the LPGA as the only South Korean woman on the tour in 1998, winning the U.S. Women’s Open that same year. In 2008, Pak was one of 45 South Korean women on the tour; and in 2019, 39 of the top 100 and 144 of the top 500 LPGA players were from South Korea. The recent successes of Japan’s Hinako Shibuno, who won the 2019 Women’s British Open, may also prove the transcontinental importance of Asian sporting role models.

This trend extends far beyond golf. Yao Ming’s appearance in the NBA brought basketball to a new level of fame in China, inspiring millions of young Chinese to play. Son Heung-min’s success in the English Premier League has undoubtedly led to a surge of men’s football in South Korea. Baseball flourished in Japan after Masanori Murakami became the first player of Japanese descent in the MLB, inspiring a wave of Japanese baseball players, including Hideo Nomo and Ichiro Suzuki. Naomi Osaka, the first Asian player to hold the top ranking in singles tennis, continues to dominate and inspire the proliferation of tennis in Japan and beyond. With his validating win earlier this month, Matsuyama may very well be poised to join the ranks of these iconic Asian athletes.

At the same time, Matsuyama’s win does not offset some of the prohibitive factors that define golf in Japan today. Golf was historically reserved for the Japanese elite, with the cost of a private club membership in Japan in 1990 averaging 50 million yen (nearly $520,000 today). Many private golf clubs continue this tradition with extremely exclusive — and expensive — memberships. Japan’s overall limited space means there is insufficient land to develop new 18-hole golf courses beyond the present 2,500 courses, which typically require 100+ acres each. With these barriers to entry, Matsuyama’s Masters win may only incrementally increase participation in golf, if at all.

Beyond the game, fans expressed hope that Matsuyama’s win may lead to less discrimination against Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities in the U.S. and abroad. This hope remains distant, embodied in the fact that Matsuyama’s win was juxtaposed by same-day news coverage of online racial abuse directed at Son Heung-min of the Tottenham Hotspurs following a soccer match against Manchester United.

Western news outlets also relied on problematic language heavily based in Asian stereotypes to cover Matsuyama’s victory. One New York Times article dedicated to his status as a national hero mentioned stereotypically Asian traits five separate times, and another titled “A Quiet Masters Winner” discusses Matsuyama as a “shy, intense and obsessive… [and] quietly working” golfer. Golf Digest’s coverage also refers to Matsuyama as the “quiet star” who remains out of the spotlight. Matsuyama may very well be quiet, respectful, and hard-working, but the decidedly stereotypical coverage of Matsuyama’s success has made his ethnicity — not his athletic achievement — the focus. This is best illustrated by the televised post-win ceremony when Matsuyama was presented his green jacket. Only two questions during his three-minute interview focused on his performance. In stark comparison, Dustin Johnson’s nearly five-minute interview during his 2019 green jacket ceremony focused entirely on his athletic performance. Until Asian players are respected across sport and recognized for their achievements rather than their ethnicities, Matsuyama’s victory unfortunately can only bring limited change.

Even though golf has attempted to divorce itself from American politics, celebrating Matsuyama as a distinctly Asian athlete brings the issue of discrimination against the AAPI community to the forefront. The PGA chose to play the Masters at Augusta National despite the host state’s passage of controversial voting laws that disproportionately affect underrepresented communities, contrasting with other sports bodies that moved similarly important competitions out of Georgia in protest. Not even one week after Matsuyama’s win, six Republican senators voted against the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act, which seeks to address the rise in anti-AAPI hate crimes during the pandemic. The reality remains clear: Asian athletes are celebrated while discrimination against AAPI and other minorities is simultaneously tolerated.

Despite these barriers in Japan and abroad, Matsuyama made it clear in his post-win interviews that his Masters win was for his home audience by speaking in Japanese. Matusyama’s choice to speak Japanese may have reflected a desire to be comfortable in the emotionally-charged environment of winning the Masters, but it also shows that his responses about winning, his process, and representing his country are intimately directed to a Japanese audience. As Matsuyama himself said in a previous satirical language class featuring other famous golfers including Tiger Woods, Jason Day, and Rory McIlroy, “I can speak English, guys.” He just intentionally chose not to.

Matsuyama’s pointed message is an important reminder that his Masters performance may not be the pinnacle of his year. Although winning the Masters is an incredible achievement for any golfer, hailing this tournament as the end-all, be-all, ignores the upcoming Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics. There is now vast speculation that Matsuyama may be asked to light the Olympic cauldron at the Games’ Opening Ceremony in July. But perhaps the greater honor lies in his participation in the Games, where he has the opportunity to not only represent his nation, but play — and even win — at home.

The author would like to thank Catherine Tao, Emi Suzuki, and Spencer Hair-Elliott for their assistance with this article.