Inside Ms. Sadat’s Beauty Salon in Afghanistan’s capital, Sultana Karimi leans intently over a customer, meticulously shaping her eyebrows. Make-up and hair styling is the 24-year-old’s passion, and she discovered it, along with a newfound confidence, here in the salon.

She and the other young women working or apprenticing in the salon never experienced the rule of the Taliban over Afghanistan.

But they all worry that their dreams will come to an end if the hard-line militants regain any power, even if peacefully as part of a new government.

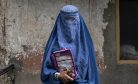

“With the return of Taliban, society will be transformed and ruined,” Karimi said. “Women will be sent into hiding, they’ll be forced to wear the burqa to go out of their homes.”

She wore a bright yellow blouse that draped off her shoulders as she worked, a style that’s a bit daring even in the all-women space of the salon. It would have been totally out of the question under the Taliban, who ruled until the 2001 U.S.-led invasion. In fact, the Taliban banned beauty salons in general, part of a notoriously harsh ideology that often hit women and girls the hardest, including forbidding them education and the right to work or even to travel outside their home unaccompanied by a male relative.

With U.S. troops committed to leaving Afghanistan completely by September 11, women are closely watching the stalemated peace negotiations between the Taliban and the Afghan government over the post-withdrawal future, said Mahbouba Seraj, a women’s rights activist.

The United States is pressing for a power-sharing government that includes the Taliban. Seraj said women want written guarantees from the Taliban that they won’t reverse the gains made by women in the past 20 years, and they want the international community to hold the insurgent movement to its commitments.

“I am not frustrated that the Americans are leaving … the time was coming that the Americans would go home,” said Seraj, the executive director of Afghan Women’s Skill Development.

But she had a message for the U.S. and NATO: “We keep yelling and screaming and saying, for God’s sake, at least do something with the Taliban, take some kind of assurance from them … a mechanism to be put in place” that guarantees women’s rights.

Last week the Taliban in a statement outlined the type of government they seek.

It promised that women “can serve their society in the education, business, health and social fields while maintaining correct Islamic hijab.” It promised girls would have the right to choose their own husbands, considered deeply unacceptable in many traditional and tribal homes in Afghanistan, where husbands are chosen by their parents.

But the statement offered few details, nor did it guarantee women could participate in politics or have freedom to move unaccompanied by a male relative.

Many worry that the vague terms the Taliban use in their promises, like “correct hijab” or guaranteeing rights “provided under Islamic law” give them wide margin to impose hard-line interpretations.

At the beauty salon, the owner, Ms. Sadat, told how she was born in Iran to refugee parents. She was forbidden to own a business there, so she returned to a homeland she’d never seen to start her salon 10 years ago.

She asked not to be identified by her full name, fearing that attention could make her a target. She has become more cautious as violence and random bombings have increased in Kabul the past year — an augur of chaos when the Americans fully leave, many fear. She used to drive her own car. Not anymore.

The women building a future working or apprenticing in the salon all dreaded a restored Taliban — “Just the name of the Taliban horrifies us,” said one.

They’re left gaming out how much compromise of their rights they can endure. Tamila Pazhman said she doesn’t want “the old Afghanistan back,” but she does want peace.

“If we know we will have peace, we will wear the hijab while we work and study,” she said. “But there must be peace.”

In their early 20s, they all grew up amid the incremental, but important gains made by women since the Taliban’s ouster. Girls are now in school, and women are in Parliament, government, and business.

They also know how reversible those gains are in an overwhelmingly male-dominated, deeply conservative society.

“Women in Afghanistan who raise their voices have been oppressed and ignored,” Karimi said. “The majority of Afghan women will be silent. They know they will never receive any support.”

Afghanistan remains one of the worst countries in the world for women, after only Yemen and Syria, according to an index kept by Georgetown University’s Institute for Women, Peace and Security.

In most rural areas, life has changed little in centuries. Women wake at dawn, do much of the heavy labor in the home and in the fields. They wear the traditional coverings that conceal them from head to toe. One in three girls is married before 18, most often in forced marriages, according to U.N. estimates.

Religious conservatives who dominate Parliament have prevented passage of a Protection of Women bill.

Afghanistan’s broader statistics are also grim, with 54 percent of its 36 million people living below the poverty level of $1.90 a day. Runaway government corruption has swallowed up hundreds of millions of dollars, rights workers and watchdogs say.

At a bakery in Kabul’s Karte Sakhi neighborhood, 60-year-old Kobra squats in a brick shack blackened by soot in front of a clay oven dug into the floor.

The work is backbreaking; smoke fills her lungs, flames scorch her. She makes about 100 Afghanis a day, the equivalent of $1.30, after paying for firewood. She is the only wage earner for her sick husband and five children.

Her 13-year-old daughter Zarmeena works by her side, helping bake and sweeping the soot-coated floor. Neighborhood women bring their dough to be baked, and Zarmeena kneads it and puts it into the oven. They yell insults at her if she accidentally drops it into the fire.

Zarmeena has never been to school because her mother needs her in the bakery, though her younger brother, at 7, is in school. “If I could go … I would be a doctor,” she said.

Nearly 3.7 million Afghan children between 7 and 17 are out of school, most of them girls, according to the United Nations Children Education Fund.

Kobra isn’t looking forward to a Taliban return. She’s Hazara, a largely Shiite ethnic minority that has faced violence from the Taliban and other Sunni groups.

But she also rails against the current government, accusing them of “eating all the money” sent for Afghanistan’s poor to feed their own corruption. For months, she has tried to collect a stipend for the poor worth about $77, but each time she is told her name is not on the list.

“Who took my name?” she said. “You have to know someone, have a contact in the government or you will never receive anything.”