As Chinese loans to Africa have been on an upward trajectory for more than a decade, there are questions about the economic consequences that large scale borrowing from China has on African economies. Particularly, there is a raging debate over whether Chinese loans to Africa are a net positive or a net drain on African economies. My research confirms at least one benefit: infrastructure loans (which account for a significant share of China’s lending) are strongly correlated with a rise in the number of business startups.

It’s not hard to imagine why this would be the case. In Dar es Salaam, the largest city in Tanzania, disruption of economic activity from frequent power outages and unreliable transport has left businesses with no choice but to invest in costly diesel generators, keep expensive backup inventories, and adopt other coping measures at a significant cost. This is especially relevant for new startups, which may be unable to adapt to expensive generators and other challenging coping strategies. Unfortunately, infrastructure deficits like the lack of reliable transport and electricity are not unique to Dar es Salaam — they are prevalent in many large African cities. Indeed, according to World Bank investment climate surveys, African firms have consistently ranked economic infrastructure deficits as an important constraint to business.

My recent study finds that new startups are thriving in African countries with a higher percentage of Chinese economic infrastructure loans. This finding supports evidence that large-scale investments in economic infrastructure such as roads, ports, electricity grids, and telecommunication networks create business opportunities and reduce doing business costs in Dar es Salaam and elsewhere in Africa.

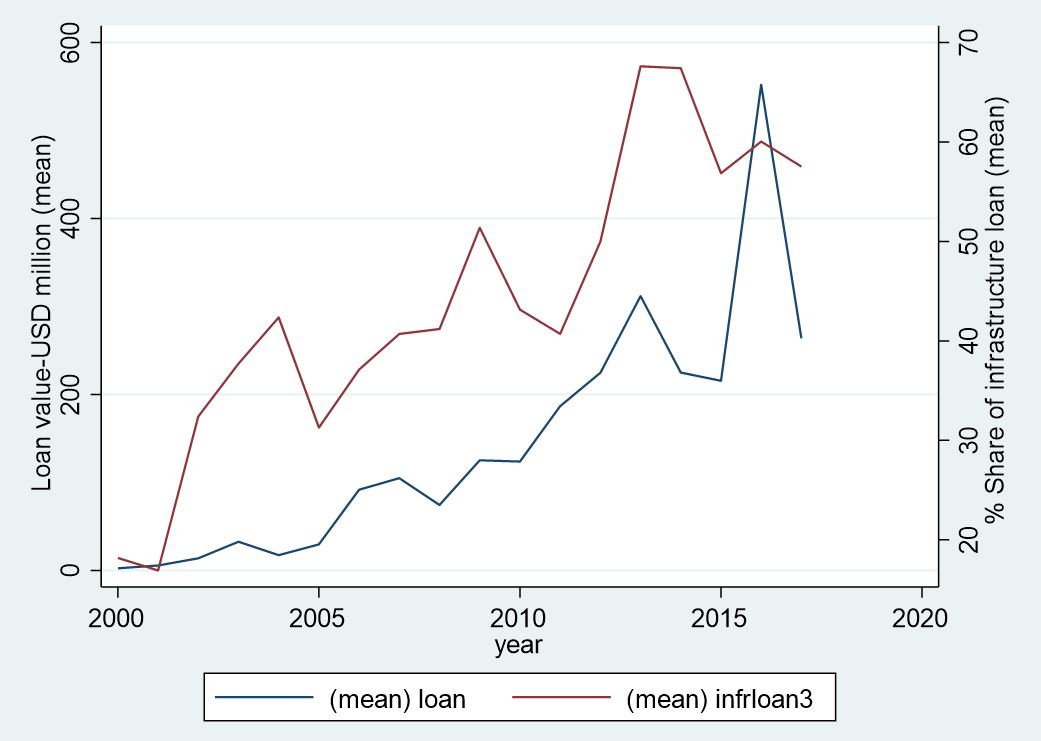

China’s average loans to Africa. Data source: SAIS-CARI Chinese Loans to Africa database (https://chinaafricaloandata.org).

Key Findings

In my study, I empirically analyzed a panel dataset of 38 African countries spanning the period between 2006 and 2018, and found robust evidence that African countries with a higher percentage of economic infrastructure loans in terms of GDP have greater entrepreneurship in the form of new business startups. Increasing total economic infrastructure loan amounts (expressed as a percent of the recipient’s GDP) by one percent is on average associated with a 3.6 percent increase in new business startup activity.

However, these benefits were not evenly spread. New firm creation is found to be significantly lower in African countries with 1) greater regulation-driven barriers to entry, 2) poor institutional quality, and 3) restricted access to private sector credit. Specifically, increasing entry regulation for firms by one procedure significantly curtails new business formation, by approximately 8.1 percent. Turning to institutional quality, a one standard deviation improvement in institutional quality raised new business creation by 77 percent. Two institutional quality dimensions (i.e., control of corruption and rule of law) are shown to be especially important for promoting new business startups. Lastly, expanding access to private sector credit by just 1 percent is significantly associated with a 2.3 percent increase in new business startup activity.

Policy Recommendations

These findings are consistent with the view that Chinese economic infrastructure loans promote new firm startups by creating business opportunities and by reducing infrastructure related costs.

Good infrastructure enables opportunities by connecting firms to their customers and suppliers, and by helping them to take advantage of modern production techniques. For example, efficient transport infrastructure links create opportunities for firms to not only buy and sell in neighboring markets, but enhance their reach to the entire world. This is particularly important for Africa, where poor transport infrastructure has been found to account for a large percent of the cost of transport – a cost that is significantly higher for landlocked African countries. Complementing efficient transport infrastructure links with access to modern telecommunications services and reliable power supply reduces barriers that impede the entry of new firms in African markets.

Clearly, Chinese loans that are used to improve the provision of economic infrastructure services in Africa can have a big impact on the entry of new firms into African markets. This is important from a development perspective because new firm creation is often credited for boosting the overall productivity and economic growth of a country through its positive effects on efficiency and innovation. In addition, newly established firms also contribute significantly to job creation.

The policy implications of my research are clear: To promote new business startups, African nations with limited fiscal space should use loans from China, prioritizing business creation opportunities and reducing the costs of doing business. Loans should target financing all the three types of economic infrastructure — transport, communications, and energy. This is crucial because these different economic infrastructures complement each other. For example, transport costs caused by poor transport infrastructure are affected by other types of infrastructure, including the extent to which telecommunications systems allow firms to track their goods in transit, and how quickly goods are cleared through customs for firms engaged in international trade. The focus should be on improving both access and reliability of infrastructure services — it doesn’t help at all to be connected to an electricity grid if there is no power supply.

But infrastructure loans and projects alone won’t guarantee a startup boom. African governments must also provide increased access to private sector financing. In World Bank investment climate surveys, African firms cite access to finance as their second biggest operating constraint after poor infrastructure. The African Development Bank notes that start-ups in particular are subject to more credit constraints.

Likewise, African countries need to strengthen the regulatory and institutional framework to create a more conducive business environment. Policies that tackle unfavorable business regulations (through entry deregulation) as well as poor-quality institutions (by combating corruption and strengthening the rule of law) are important. According to the African Development Bank, the harmful consequences related to regulatory and institutional constraints often fall disproportionately on new entrepreneurs.