The recent decision by Japan to confer a prestigious award on the former home minister of Bhutan is being seen as a direct slap in the faces of the tens of thousands of Bhutanese citizens whose lives were unalterably changed decades ago after the regime evicted them from their country.

Former Minister Dago Tshering was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun in recognition, according to a news release issued by the Japanese Embassy in New Delhi, for his “contributions to strengthening the relationship and friendship between Japan and Bhutan.”

Bhutanese of Nepali descent who are now exiled from their country are shocked and puzzled. Is Japan unaware of Tshering’s past? Is the country turning a blind eye to how Tshering treated his own countrymen and women more than two decades ago? And if so why, and why now?

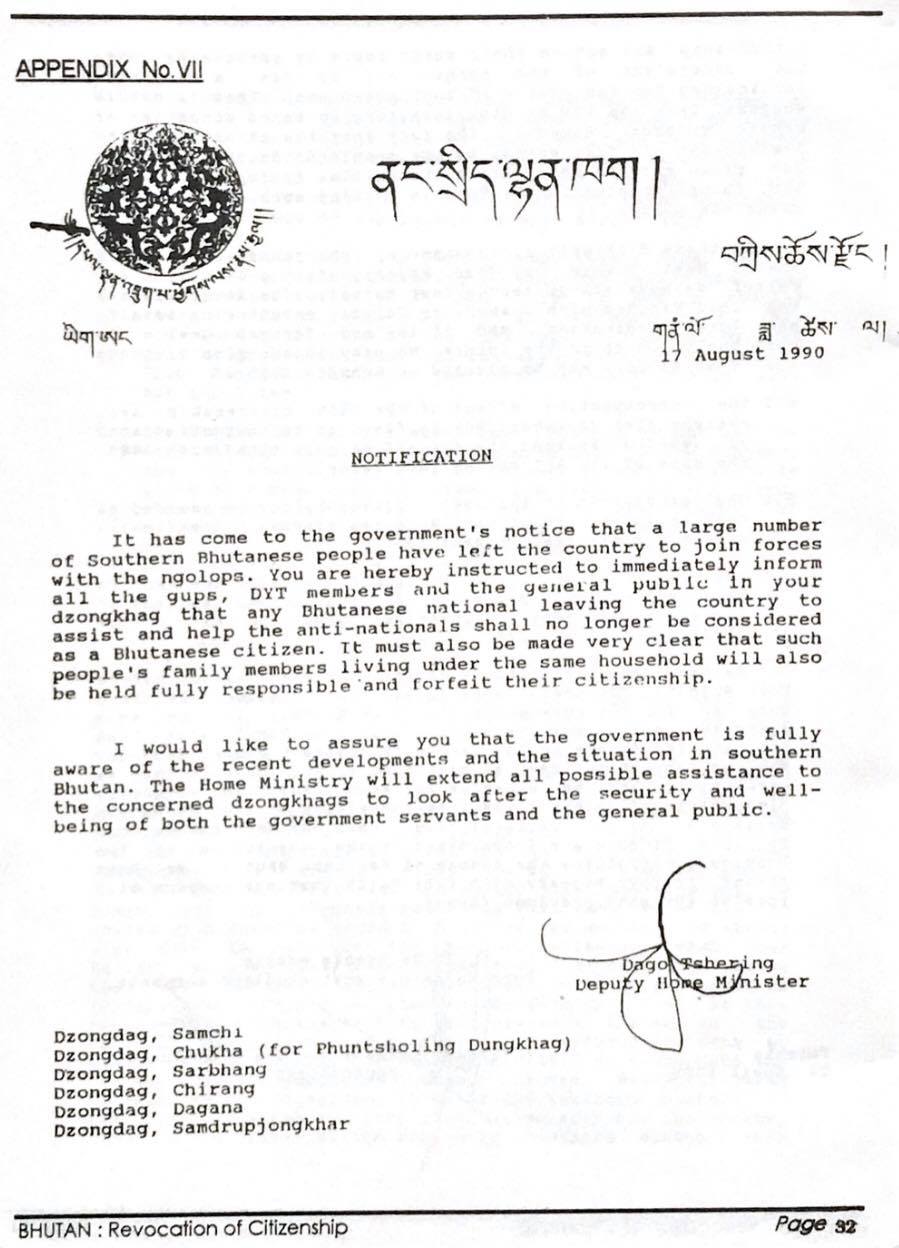

On August 17, 1990, in his capacity as deputy home minister, Tshering issued a directive capriciously revoking the citizenship of southern Bhutanese and their families who had fled the country. The directive was clear and unambiguous. It read:

“It has come to the government’s notice that a large number of southern Bhutanese people have left the country to join forces with the ngolops. You are hereby instructed to immediately inform all gups, DYT members and the general public in your dzongkhag that any Bhutanese national leaving the country to assist and help the anti-nationals shall no longer be considered as a Bhutanese citizen. It must also be made very clear that such people’s family members living under the same household will also be held fully responsible and forfeit their citizenship.”

The directive issued by Dago Tshering revoking the citizenship of Nepali-descent Bhutanese. Courtesy/AHURA-Bhutan.

A year later, Tshering ramped up his campaign against Bhutanese people of Nepali descent who had been welcomed into the country decades earlier in order to populate the southern region for revenue generation as well as provide manpower for building infrastructure. In return, they were awarded citizenship for their hard work.

This led to opposition from the ethnic Nepali population of Bhutan who had been forced out of their homeland and who viewed the policy as discriminatory. Tshering, in response mobilized the state machinery in a campaign of looting, arson, raids, arrests, torture, rape and the eventual eviction of southern Bhutanese from their traditional homeland, thereby rendering them stateless.

A report in a September 1990 India Today magazine made clear Tshering’s views. It quoted him explaining the decision to stop teaching Nepali in Bhutan’s schools by saying that “In our experience the Nepalis identify more with Nepal than with us.”

My own father and thousands of other people were imprisoned for months and tortured both mentally and physically during this wave of terror against the Nepali-speaking population. “You belong to Nepal, not Bhutan,” my father recalled Tshering saying.

At the time, the outside world was largely unaware of the atrocities that were unfolding because the regime had total control over the country’s media. International human rights and media organizations were not even aware of the ethnic cleansing that was taking place. Once aware, Ingrid Massage, a former researcher at Amnesty International, described the situation as “one of the most invisible and forgotten human rights issues.”

During his time as Bhutanese ambassador to Japan, between 1999 and 2008, Tshering won recognition for boosting high-level visits and cultural exchanges between the two countries. It is, perhaps, understandable for Japan to appreciate such historical diplomatic ties. But, at the same time, Japan must also understand and appreciate the impact of the other side of Tshering’s career — that of the ethnic-cleansing of the Nepali-speaking population in Bhutan and the hounding of them when resettled.

For those who have suffered at the hands of Tshering, the award by Japan will be seen as the country valuing diplomacy over the human rights of the thousands who suffered because of the former home minister’s policies.

Tek Nath Rizal, a human rights activist and former Amnesty International “prisoner of conscience,” who spent a decade in prison in Bhutan, said it was beyond comprehension how the former ambassador has been recognized with an award.

“I cannot fathom how a country like Japan, which has championed for the guarantee of human rights and democracy in Bhutan in various forms for years, has now decided to award Dago Tshering, a racist, ruthless and corrupt former home minister,” he said.

Rizal said that if Bhutan had an independent and fair justice system, Tshering would have already been tried and punished for the crimes he committed against the Nepali-speaking population in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Rizal also said that while he was on hunger strike in Chemgang jail, better-known to Bhutanese political prisoners as a torture chamber, Tshering sent him a letter saying that he would have been long dead had the king not had mercy on him, and warning that he should “stop advocating for fellow prisoners’ fair trial in the court.”

The acting president of the exile-based Bhutan National Democratic Party, Dr. DNS Dhakal, said Japan’s decision to confer this award on Tshering is designed to save him from punishment by the Bhutan government for the crimes that he committed on the Lhotshampa (Nepali-speaking) Bhutanese population.

Dhakal also suspects that the award may have been announced following consultations with royal family members in Bhutan.

Given that Tshering is the first Bhutanese national to be recognized with the Order of the Rising Sun, victims in the diaspora wonder whether Japan might be trying to establish political influence in Bhutan, which is closely connected with and financially dependent on India.

Jogen Gazmere, another former Amnesty International “prisoner of conscience” who has now resettled in Australia, claims that Tshering presented falsified figures, generated through the census of 1988 — which is considered by many to have been a sham — in order to encourage the assembly to agree to the expulsion of southern Bhutanese. As a result, he says, Tshering is directly responsible for the decades of trauma and suffering that tens and thousands of southern Bhutanese children, women and elderly people have suffered.

As a neighbor and a close ally, Japan must be fully aware of how the Bhutanese monarchy, and the likes of Tshering and his confidantes, have played in evicting almost 20 percent of the country’s Nepali-speaking and Sharchop populations from the Himalayan kingdom. To confer such a prestigious award on an individual who, victims believe, was the mastermind behind the ethnic-cleansing policy is a disgrace.

Dr. M. Ringhofer who chairs the Association of Human Rights Activists (AHURA)- Japan said that, as a home minister, Tshering had been highly involved in the treatment and expulsion of the refugees. “I was astonished that a Bhutanese is receiving such an order, but otherwise not surprised, if you look at the quite short, but intimate relationship between these two countries and between the Japanese emperor’s family members and the kings of Bhutan and his relatives.”

It is unlikely that the Japanese aren’t aware of Tshering’s involvement in these destructive policies. The question on the minds of many in the exiled Bhutanese community around the globe is why has the award been given, and what is the likely consequence for not only Japan and Bhutan, but also for the exiled community abandoned by their original home country and still traumatized from the policies forced on them by Tshering a generation ago.