In April 2021, the Cameroonian government announced that it was in talks with Rothschild and Co. to obtain advice on a Eurobond sale that would be used to repay a portion of the $750 million in debt that it sold in 2015. The announcement that Cameroon would again need to enter the Eurobond market to obtain credit came after the International Monetary Fund (IMF) classified the central African country as at high risk of debt distress, both to internal and external lenders. The classification of Cameroon as facing a high risk of debt distress was made in January 2020, before the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has undoubtedly worsened the fiscal and monetary standing of the country. The credit situation in Cameroon may further deteriorate as an IMF extended credit facility (ECF) that has provided the country with monetary assistance is due to expire in summer 2021. While the IMF and Cameroon have engaged in talks about renewing the ECF it is unclear if that will occur, particularly in light of recent news that a $335 million loan issued by the IMF to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic had been misappropriated.

Cameroon finding itself at risk of debt distress is not a new occurrence and is a result of the country’s borrowing habits over several decades. In 2007, public debt was only 12 percent of Cameroon’s gross domestic product (GDP), and by September of 2020 the figure had increased to over 45 percent of the country’s GDP. While much of the recent attention has focused on Cameroon’s Eurobond holdings and multilateral debt, over two-thirds of the country’s debt is external. Out of Cameroon’s external debt, 61 percent is owed to China, making Beijing the country’s largest creditor. Therefore, to understand Cameroon’s risk of debt distress and the continuous credit problems that the country is facing, it is imperative to examine its debts to China.

Types of Debts Issued by China to Cameroon

China has issued over $6.2 billion in loans to Cameroon, the majority of which broadly concern infrastructure and energy. The majority of these loans are for major projects that are at least partially funded by the Cameroonian government. In many cases, the Export-Import Bank of China will fund most of an initiative through a loan and the Cameroonian government will be responsible for paying upfront around 15 percent of a project. The financing that the government of Cameroon is required to provide for the projects has at times slowed the disbursement of Chinese loans, which partially explains why 28 percent of all undispersed external debt in Cameroon is held by China. Notably, the majority of Chinese loans to Cameroon finance large and highly visible projects that are implemented by Chinese firms.

The largest source of Cameroon’s debt to China is the ongoing construction of a deep-water port in the town of Kribi in the southern region of the country. The agreement between the Export-Import Bank of China and the government of Cameroon to finance the port’s construction was first signed in 2011 and saw a concessionary loan of nearly $400 million granted. This was furthered in 2017 when the Export-Import Bank of China issued a $680 million loan for the second phase of the port’s construction. $150 million of the loan was concessional, whereas the rest was a preferential buyer credit agreement. Eighty-five percent of the financing of the port is provided by China, while the remainder is from the Cameroonian government. The state-run China Harbor Engineering Corporation (CHEC) is overseeing the construction of the port.

It is widely agreed that the construction of a deep-water port in Kribi is needed. Currently, over 90 percent of Cameroon’s maritime trade goes through the port of Douala, which is filled with sediment and is not deep enough for many ships. Once completed, the port in Kribi will be the largest in Central Africa and will be connected by railways to iron ore mines in the east of Cameroon. However, the project has caused resentment among the local community where the port is being constructed. During the process of construction, the village of Lolabe had to be destroyed, and its 400 residents were displaced. While the Cameroonian government was responsible for the displacement and embezzling funds allocated for compensation, many see the Chinese government as at best complacent in the matter. Locals complain of division between the approximately 300 Chinese workers on the project and Cameroonian laborers. Cameroonian laborers have also complained of mistreatment and abuse by their Chinese supervisors. The fact that the only two financers of the project are the Export-Import Bank of China and the Cameroonian government has also caused concerns that the port may need to be leased to China if Cameroon were to default on its debt, as occurred in the case of Hambantota in Sri Lanka.

The second largest source of Chinese debt issued to Cameroon is the Yaoundé water supply project from the Sanaga River (PAEPYS) which aims to address water scarcity challenges in the Cameroonian capital and surrounding localities. Once completed, the project will significantly increase the amount of water supplied to the city, and according to the Cameroonian government will end the need for the city’s residents to ration water. Eighty-five percent of the project is financed through a loan worth over $678 million from the Export-Import Bank of China, with the remaining 15 percent being provided by the Cameroonian government. The construction of the project is being overseen by the China National Machinery Industry Corporation, popularly known as Sinomach, a state-owned enterprise. The project was originally slated to be completed in December 2020, although the Cameroonian government has announced that it will be delayed until July of this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the project has the potential to address the pertinent issue of water shortages in Yaoundé, the financing of the project is solely done by the Cameroonian government and the Export-Import Bank of China, making it unclear what procedures may be in place should Cameroon not be able to repay the $678 million it will owe to China after the project is completed. However, the Cameroonian government has rejected the notion that the project is an instance of so-called “debt trap diplomacy.”

The third largest source of Cameroon’s debt to China is the Memve’ele hydropower dam project located on the Ntem river in the south region of the country. Once completed, the dam will have the potential to generate 211MW of hydroelectric power, which the Cameroonian government hopes can address the electricity deficit in the country where approximately 62 percent of the population do not have reliable access to electricity. The project is financed by a $541 million loan from the Export-Import Bank of China, in addition to $190 million from the African Development Bank (ADB), and $110 million from the Cameroonian government. This differs greatly from the two aforementioned projects, which are solely financed by China and Cameroon without a third party.

The project was originally being implemented by a British firm, but in 2009 the Chinese state-owned hydropower company Sinohydro took over the project. Construction of the dam began in 2013 and was supposed to be completed by 2017, although the project has experienced many delays. As of December 2020, the Cameroonian government claimed that the construction of a transmission line would be completed by March of this year and that commercial commissioning for the power plant would begin in September. The Memve’ele dam has been listed by the World Bank as a project that costs six to eight times more than similar initiatives in countries with comparable levels of development to Cameroon, leading to concerns of corruption and overpaying those assisting in implementation. There has also been opposition to the project from local communities who have been removed from their land to allow for construction. This is the case in Nyabizang, where the dam is being built, in addition to communities where transmission lines are being built to transmit hydropower to the Cameroonian capital of Yaoundé.

While the Kribi deep water port, the Sanga River water supply project, and the Memve’ele hydropower dam constitute a large percentage of Cameroon’s debt to China, the projects are by no means the totality of it. In total, Cameroon owes China at least $5.2 billion that was issued through at least 45 loans. Projects related to transport, energy, technology, and water all occupy at least a $1 billion of debt. Notably, at least $333 million of the loans are related to the Cameroonian military, which has played a key role in human rights violations in conflicts across the country.

Risk of Default and Debt Relief

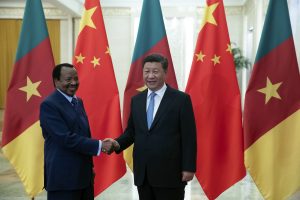

The potential of Cameroon not being able to repay its debts to China became evident when Yaoundé was not able to fulfill some terms of its debt, which resulted in tougher financial conditions that began in 2017. In 2018, on the sidelines of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) held in Beijing, the Cameroonian government formally requested that its debt to China be restructured. The severity of the situation and the real probability that Cameroon may not be able to repay its debts was underscored in January 2019 when Cameroon unilaterally withheld debt service payments to China, to which the Export-Import Bank of China responded by freezing payments for projects in Cameroon.

In July 2019, Cameroon and China reached an agreement to restructure the payment of debts during the visit of Yang Jiechi, the director of the Central Foreign Affairs Commission, to Yaoundé. The restricting of the debt saw a total of $250 million of payments deferred over the following three years, although Cameroon would still be required to pay back the total amount of each loan by its original due date. In short, the relief would only be temporary, and Cameroon would still have to repay the total amount that it owed to the Export-Import Bank of China. A total of $78 million of Cameroon’s debt to China was canceled, although the debt was composed of payments that were supposed to be made to China the previous year but were not. This followed previous cancellations of Cameroon’s debt to China in 2001, 2007, and 2010.

However, it is important to note that the quantity of Cameroon’s debt to China that has been forgiven pales when compared to that of other countries. For instance, in 2006 France cancelled $195 million of Cameroonian debt, and issued further $474 million of debt relief in 2011. Canada forgave $227 million of debt owed to Ottawa by Yaoundé in 2006. In short, while the debt restructuring agreed to in 2019 provided temporary relief to the Cameroonian government, it did not tangibly change the difficulties that Yaoundé would face in paying its debts to Beijing.

In May 2020, Cameroon again delayed its debt payments to China through the debt service suspension initiative (DSSI) agreed to by members of the G-20, which includes China. This greatly benefitted Cameroon, as over half of its bilateral debts are to China. Specifically, in 2020 China deferred a payment from Cameroon worth over $55 million, and in 2021 Beijing deferred a further payment worth nearly $20 million. These payments will now be served between 2022 and 2025, in addition to the payments that were already scheduled for those years. This likely means that Cameroon will face increased difficulties paying its debts into the mid-2020s, due to both the delayed payments to China in addition to the delayed payments that Yaoundé will eventually need to make to Paris Club creditors.

Despite the temporary rescheduling of debt payments, China continues to remain the top source of Cameroon’s debt. The difficulties that Cameroon will face regarding its debts to China will only increase going into the mid-2020s when large sums of debt are due to be serviced. This situation regarding Cameroon’s debt to China in addition to other creditors raises serious questions about the Central African country’s ability to service its debts. This is not only due to the quantity of the debt, but the continued poor economic figures in the country as a result of political instability and the COVID-19 pandemic. What might happen if Cameroon reaches a point where it is not able to service its debts? The possibilities include, but are not limited to, defaulting on its debt, as occurred in Zambia in 2020, or potentially ceding temporary ownership of facilities funded by external creditors.