May 4, 2021 marked the 116th anniversary of the arrival of ethnic Koreans to Latin America. In April 1905, the first thousand Korean labor migrants boarded a British cargo ship in the Korean port of Chemulpo (present-day Incheon). The migrants were drawn away from the increasingly tumultuous Korean peninsula by the promises of stable work and regular wages in faraway Mexico. A month later, on May 4, the ship arrived at the Mexican port of Progreso, near Merida, on the Yucatan peninsula.

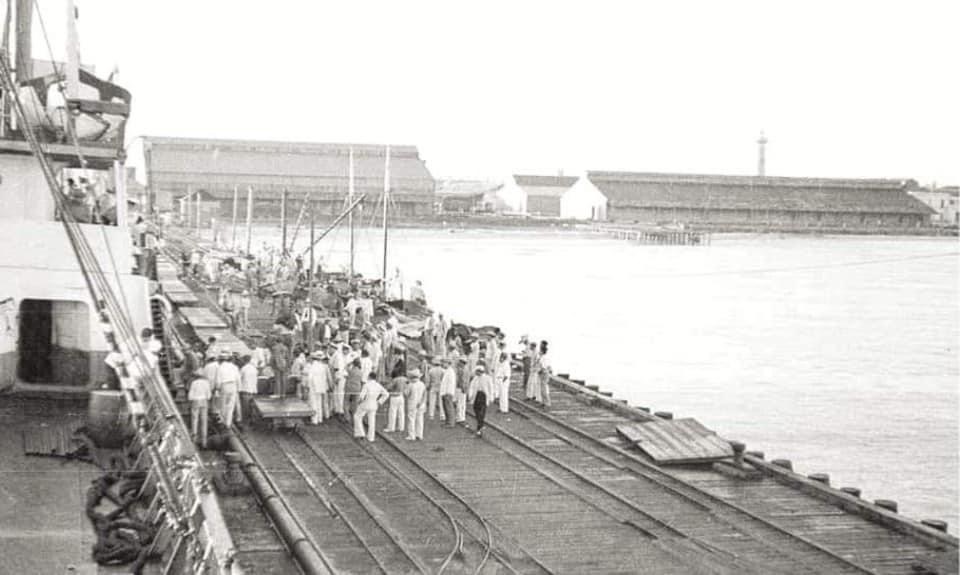

Arrival of the first Korean immigrants to Mexico’s Port of Progreso on the Yucatan peninsula in mid-May 1905 (public archives).

In January 1903, the first shipload of Koreans had arrived in Hawaii, then a recently incorporated territory of the United States, to work on pineapple and sugar plantations. By 1905 more than 7,000 Korean labor migrants had departed Chemulpo for work in Hawaii.

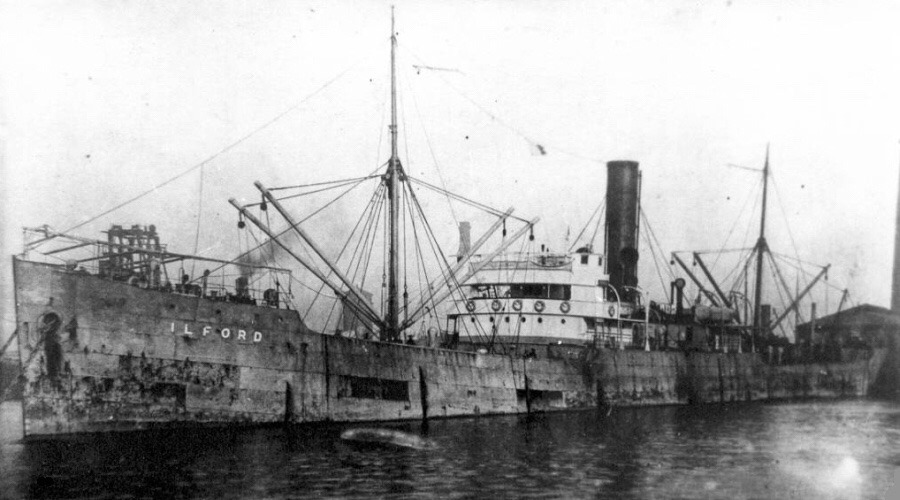

British cargo ship S.S. Ilford took the over 1,000 Koreans to Mexico on April 4, 1905. (public archives)

The history of Korean immigration to the Americas began with sweat and exploitation. The British lured Koreans with promises of four and five-year work contracts, but upon arrival, the Koreans found themselves sold into indenture servitude on the Yucatan’s henequen plantations, where local Yaqui and other indigenous groups were also exploited for labor.

In 1910, Japan annexed Korea and the Koreans in Mexico effectively lost their nationality.

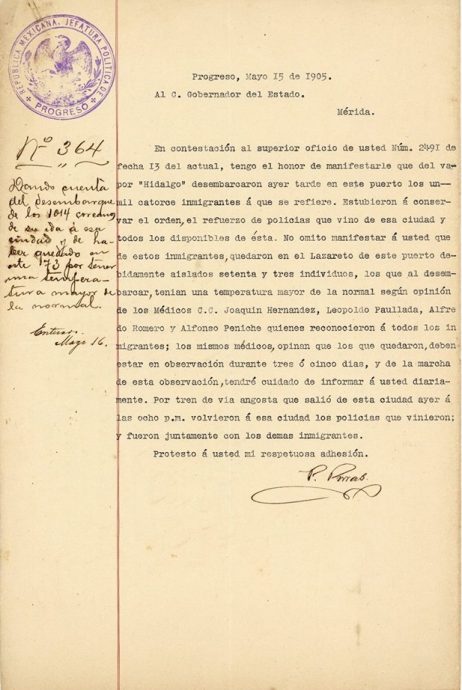

Documents confirming the arrival of ethnic Koreans to the Port of Progreso on May 14, 1905. (public archives)

Some Koreans tried to escape from the dire situation in Mexico to Hawaii through San Francisco with no success. Around 1921, when demand for henequen fiber declined, 288 Korean laborers managed to escape to Cuba from the Mexican port in San Francisco de Campeche. The roughly thousand-strong Korean diaspora in Cuba today cites its roots in those nearly 300 migrants.

With the passage of time, the Koreans who remained in Mexico managed to not only survive but eventually integrate themselves in the local society. Through them, the wider story of Korean diasporas became woven into Mexico’s own complicated history.

A second wave of Korean migration to Mexico was triggered in part by the economic crises in South America in the 1970s and ’80s. South Koreans, as well as Argentine and Paraguayan Koreans, came to Mexico seeking better opportunities and living conditions.

Some of the first Mexican Korean laborers on Yucatan’s henequen haciendas (public archives)

At the end of 1990s, there were almost 20,000 ethnic Koreans living in Mexico. Most recently, the Mexico City Association of Korean Descendants claimed in mid-March 2021 that around 30,000 ethnic Koreans resided Mexico.

Despite this long presence in Mexico, it was only in the early 2000s that the Mexican Korean diaspora gained greater recognition. This was facilitated, in part, by South Korea’s pragmatic foreign policy, encompassing strong public diplomacy and cultural soft power, matched with outreach to various diaspora communities not only in Eurasia, but in Latin America as well.

Monument in Merida commemorating the 100th anniversary of the first Koreans’ arrival to Mexico. (Wikimedia Commons)

In the last two decades, South Korea has managed to reconnect itself not only with the post-Soviet Korean diaspora – known as the Koryo Saram, they number around half a million and are spread across the former Soviet Union – but also with the tens of thousands of ethnic Koreans scattered around Mexico.

Reengaging its diaspora serves many purposes for South Korea and the communities of Koreans abroad. On one hand, the diaspora longs to reconnect with their cultural and linguistic roots, which lie in a now prosperous homeland. On the other, South Korea’s insatiable demand for energy resources, particularly its quest to diversify its energy partnerships beyond the Middle East, has led Seoul to seek out connections abroad on which to build.

Descendants of ethnic Korean deportees in Uzbekistan dressed in festive South Korean styled clothes, waiving and pledging allegiance to South Korean flag besides their national flags (Koryo-saram.ru)

The transitional post-Soviet economies and the emerging markets of Latin America are ideal economic partners. South Korea – a true “middle power” – has invested in establishing relations, promoting free trade and travel with other middle powers similarly “stuck” between great powers in their respective regions. There are number of similarities in South Korea’s models of bilateral interaction – economic, political, cultural – with its major trading partners in both Eurasia and Latin America.

In terms of bilateral trade, Mexico and Eurasia (in this case referring to Russia plus the states of Central Asia) are South Korea’s largest partners in each respective region. In 2019, South Korea’s total trade volume with Mexico amounted to $21 billion, having grown over 70 percent in the last decade; meanwhile, its trade with Russia reached $22 billion, having grown over 100 percent in the last 30 years, and trade with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, combined, hit $15 billion in 2021.

South Korean foreign direct investment into the same economies is another important illustration of growing ties. In 2019, South Korean FDI into Central Asia’s top two economies exceeded $7 billion and its investments into Russia topped $4 billion in 2020; while FDI into the Mexican economy hit almost $7 billion by early 2021.

Ethnic Korean descendants in Uzbekistan in April 2019, together with the Uzbek and South Korean presidential couples at the opening ceremony of Korean Culture and Art House (Sputniknews.ru)

The above countries share not only a very high degree of export and import complementarity with South Korea – mostly in crude petroleum as a principal product of exports from both regions (45 percent respectively from Mexico and Russia and over 90 percent from Central Asia) and machinery hardware and vehicle parts being the main categories of imports from South Korea – but also host significant numbers of ethnic Korean immigrants (hundreds of thousands dispersed across Eurasia and Latin America).

It is particularly interesting to view in parallel South Korea’s unique mixture of foreign policy and public diplomacy paired with soft power and diaspora outreach in both regions.

Mayor of San Francisco de Campeche and descendants of ethnic Koreans in Mexico at the Korea Day celebrations in 2021 (Facebook)

As a result, ethnic Korean diasporas have become more than just proponents of South Korean cultural power, but important political and economic players in the efforts of the involved middle powers to gain market access and influence.

This is especially important from the position of leading members of the Korean diasporas in Mexico and Eurasia, those actively engaged in (and engaging with) local governments, promoting South Korean economic, social, and political agendas under the banner of mutual cultural cooperation.

The first Korea Day in Mexico on May 4, 2019 with festivities in Yucatan and Campeche (Facebook)

For instance, the head of the South Korea-Mexico Friendship Society, David Bautista Rivera Morena, is also a deputy in the Mexican Congress. On March 18, 2021, the Mexican Chamber of Deputies approved with an overwhelming majority of votes a proposal from Morena to mark May 4 each year as Korean Immigrant Day across Mexico.

Morena’s initiative brought what had been a local holiday, marked on May 4 in the states of Yucatan and Campeche since 2019, to the national level. Korea Day was originally (and still is) celebrated in Yucatan and Campeche after direct efforts by the South Korean Embassy, then under Ambassador Kim Sang-il, to mark the 100th anniversary of the provisional Korean government in 1919.

A day before the Korean Immigrant Day vote, the statue of Greetingman or El hombre que saluda – created by South Korean sculptor Yoo Yong-ho in 2020 to commemorate the 115th anniversary of the departure of the first Korean labor migrants to Mexico – was installed in Merida, a twin city of Incheon since 2007, on the Avenue of the Republic of Korea.

Greetingman’s unveiling ceremony on Republic of Korea avenue in Merida in mid-March 2021 (Facebook)

A turquoise nude male figure inclined in a traditional Korean-style courteous bow represents the gratitude to Mexico’s generosity in receiving Korean migrants over a century ago in spite of the dark slave trade history behind their original arrival.

The street itself was renamed thusly in December 2017, following efforts by then South Korean Ambassador Chun Bee-ho to celebrate the 55th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relationship between South Korea and Mexico.

Similarly, the Korea-Mexico Friendship Hospital was opened in Merida in 2005 after South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun’s visit to Mexico.

In each of the above cases, South Korea has deftly wielded diplomatic and cultural tools to both reach out to the Korean diaspora in Mexico and through them connect with the Mexican government. The marking of the arrival of the first ethnic Koreans to Mexico with a federal level holiday underscores the efforts of the South Koreans and the position of ethnic Koreans in the region. This is something no other Asian diaspora in Mexico and no other Korean diaspora community in the world has achieved.

Please check out part 2, “Embracing Shared Interests, Mis-remembering History: South Korean Diaspora Outreach.”

Victoria Kim previously wrote about the Soviet deportation of Koreans to Uzbekistan (available in parts one, two and three), about General Nam Il, who signed the armistice on behalf of North Korea in 1950, and about her recent journey through North Korea on a passenger train for The Diplomat.