Please check out part 1, “The Korean Diasporas in Mexico and Eurasia.”

South Korea’s outreach to ethnic Korean diasporas has spanned the globe, from Mexico to Eurasia. The recognition in the former Soviet states of Central Asia of their ethnic Korean minorities – the Koryo Saram, the descendants of Koreans deported on Stalin’s orders from the Soviet Far East beginning in 1937 – mirrors the successful recognition of the Korean diaspora community in Mexico. In both cases, acknowledgement of the social and cultural ties between the diaspora and South Korea dovetailed with extant economic and political interests.

Mexican Korean descendants together with the South Korean Embassy corps in Campeche on Korea Day, May 4, 2021. (Facebook.com)

2017 marked the 80th anniversary of the 1937 deportation – the first, though not the last, deportation of an entire ethnicity within the Soviet Union. The anniversary was widely commemorated across Eurasia with major academic conferences, official state events, plays, and concerts throughout the former Soviet Union and South Korea.

The tone and tenor of these celebratory events suggested a desire to rewrite history via a shift in focus from uncomfortable attention on the facts of the deportation – a grave human rights abuse instigated by political paranoia in the Soviet Union about Japanese spies among ethnic Koreans in the Far East prior to World War II – to the perceived benevolence of those societies that received the deportees.

Scene from the concert “Uzbekistan is our common home” performed in Tashkent in November 2017, at the 80th anniversary of the 1937 deportation of ethnic Koreans to Central Asia (Koryo-saram.ru)

Stories of how lavishly friendly the “Stans” were toward the exhausted Koreans, taken by train across the full width of Siberia and dropped off in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, exemplify the best traditions of the Soviet ideology of the “friendship of nations.” How warmly the Central Asians greeted the Koreans brought into their midst was a refrain often repeated in official statements time and again at each and every event across Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and even in South Korea. This focus was also reflected in numerous gestures of appreciation unveiled around the 80th anniversary by the Korean diaspora and with the heavy involvement of the South Korean government.

Another scene from the same concert arranged for Moon Jae-in’s official presidential visit to Uzbekistan in April 2019: a mix of folk Uzbek dance with a traditional South Korean drum performance (Kun.uz)

One reason for the pronounced participation of the South Korean government in these celebrations is that – besides the 80th anniversary of the 1937 deportation and the subsequent arrival of ethnic Koreans to Central Asia – 2017 was also the 25th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between South Korea and Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan in 1992. That anniversary mattered most, but harking back to the generosity of Central Asians toward the deported Koreans served to further ground relations more solidly in history.

A Koryo Saram folk dance group in front of the Uzbek-Korean Friendship Monument (Courtesy of Victoria Kim)

Similarly to the 2021 erection of Mexico’s Greetingman, in early July 2017 during the visit of then-Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon to Uzbekistan, the mayors of Seoul and Tashkent officially inaugurated a monument dedicated to the warm welcome extended by Uzbeks to the deported Koreans and the friendship between them.

The monument stands in the Friendship Garden in front of Seoul Park. The park was a 2010 gift from Seoul, following South Korean President Lee Myung-bak’s 2009 visits to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, during which Tashkent and the Korean capital became sister cities.

Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoev later in 2017 made an official visit to South Korea.

Moon Jae-in’s virtual welcome to Uzbek Korean compatriots during the 2017 concert “Uzbekistan is our common home” (Koryo-saram.ru)

Across four South Korean presidential regimes, the names of the relevant strategy changed but always remained the same: to strengthen bilateral political and economic ties with Eurasia, mirroring the aims of South Korea’s strategic partnership with Mexico.

On its website, the South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs remarks that the Central Asian region, rich in natural resources, is “another Middle East.”

In 2019, parallel events in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan demonstrated South Korea’s continued interest in deepening ties in the region.

During Moon Jae-in’s first presidential visit to Central Asia in April 2019, the presidents of South Korea and Uzbekistan unveiled the House of Korean Culture and Art in Tashkent. Later that year, in September, a local Korean ethno-cultural center erected a Monument of Gratitude to the Kazakhs from the Korean people in Karaganda’s central park, marking the 30th anniversary of the center’s establishment.

Unveiling of the Monument of Gratitude to Kazakhs from Koreans in Karaganda in September 2019 (Ekaraganda.kz)

While the Kazakh ceremony had a much more local flair, the story of Uzbek House of Korean Culture and Art became notorious.

Ex-South Korean president Park Geun-hye meets ex-Uzbek president Islam Karimov in 2014 (Wikipedia.org)

Back in June 2014, during an official visit of then-South Korean President Park Geun-hye to Uzbekistan, then-Uzbek President Islam Karimov expressed interest in the construction of a house of Korean culture in the country. The South Korean government immediately pledged over $5 million toward the construction and the donation of the house to Uzbekistan’s Korean Cultural Centers Association.

Korean Culture and Art House in Tashkent, Uzbekistan (Koryo-saram.ru)

Just as the head of the South Korea-Mexico Friendship Society, David Bautista Rivera Morena, is also a member of the Mexican Congress, the chairman of Uzbekistan’s Korean Cultural Centers Association, Victor Park, is a deputy in the Uzbek parliament.

The mastermind behind the construction of the Korean Culture and Art House in Tashkent at its later stages and main organizer of the 2017 and 2019 commemorative concerts “Uzbekistan is our common home,” Victor Park received two medals during President Park’s visit to Uzbekistan in 2014: the Friendship Order from Karimov and the Camelia Medal from Park Geun-hye.

Victor Park with the presidents of South Korea and Uzbekistan at the opening of Uzbek House of Korean Culture and Art in Tashkent in April 2019 (Sputniknews.ru)

In Russia, the key members of the Joint Russian Union of Koreans – an organization representing interests of the Korean diaspora in the Russian Federation – are active members of the Russian government, many of whom have been awarded with various medals by Vladimir Putin and South Korean leaders.

Key members of the Joint Russian Union of Koreans with state medals and awards from South Korea and the Russian Federation (Koryo-saram.ru)

In March 2021, Putin also gave a Friendship medal to Valentin Park, who in 2015 helped unveil a monument to the Friendship of the Korean and Russian peoples. That same year, he received another state medal – “For good deeds.”

Moon Jae-in and Vladimir Putin at the Far Eastern Forum in Russia in September 2017 (Wikipedia.org)

Park heads the Association of Korean Organizations of the Maritime Region. The first Koreans arrived to the Russian Far East in the tumultuous 1860s and lived there until the 1937 deportation. Thus, Russian-Korean contact stretched much further back in time than the official 30 years of diplomatic relations between South Korea and the Russian Federation marked in 2020.

First ethnic Koreans immigrants in the Russian empire, late 19th century (public archives)

While truly rising to its global “middle power” status over the last 20 years, South Korea has masterfully navigated the murky waters of the sometimes uneasy cultural and ethnic relations with the overseas Korean diasporas, who have fully assimilated into Latin America and Eurasia.

In Mexico, current South Korean Ambassador Suh Jeong-in has put forth new initiatives aimed to bring the Mexican and Korean people even closer: searching for Mexican veterans of the Korean War – even though Mexico remained neutral during those years and the only possibility of serving in that war for Mexicans was in the U.S. Army and under the American flag – and giving awards to the descendants of the ethnic Koreans who supported Korea’s struggle for liberation from the Japanese and 1919 independence movement fighters.

Award ceremony for the descendants of Korean patriots in Mexico city in late April 2021 (Facebook.com)

South Korea hopes to sign free trade deals with both Mexico and Uzbekistan, commercially linking the country even further with Latin America and Eurasia.

The record breaking biggest bibimbap in Campeche on Korea Day (May 4, 2021) made by Mexican Korean descendants and sponsored by Hyundai and the Overseas Koreans Foundation (Facebook.com)

The bonhomie, statues, holidays, and awards exchanged between South Korea and both Mexico and Eurasian countries like Uzbekistan obscure the darker realities of how ethnic Koreans arrived, and were initially treated, in both regions. The first generations of ethnic Korean immigrants were subjected to what we now recognize as crimes against humanity.

Ethnic Korean deportees in the Kazakh steppe in 1937 (Public archives)

The first thousand ethnic Koreans to arrive to Mexico were essentially slaves sold off by British traders to Mexican henequen plantation owners in Yucatan in the early 1900s; the nearly 200,000 ethnic Koreans deported by Stalin to Central Asia were but chattel in cattle cars rumbling across Siberia, the victims of the Soviet Union’s purges of minorities suspected of disloyalty. In both places, Korean blood stains the pages of history and the memories of descendants alike.

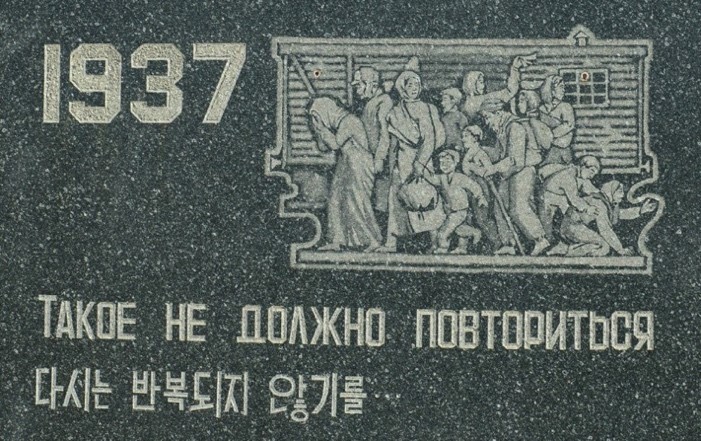

A memorial to the 1937 deportation of ethnic Koreans in Ushtobe, Kazakhstan. (Courtesy of Victoria Kim)

It is simpler to mis-remember and mis-represent the past: Even South Korean President Moon in 2019 praised the “warm welcome” given to the “homeless” Koreans who arrived to Uzbekistan to provide their offsprings with a more generous future. Local Mexican and Uzbek newspapers have long echoed the same themes.

On May 4, 2021, the first Korean Immigrant’s Day in Mexico was still celebrated as Korea Day in Yucatan and Campeche (Facebook.com)

While Russia and Kazakhstan paid nominal reparations to descendants of the originally deported Soviet Koreans in the more liberal early 1990s, in the late 2000s even the word “deportation” itself was swapped out for a more politically correct and milder sounding “forced resettlement” across the former Soviet Union, in most official remarks and publications by major post-Soviet historians and academics when referring to the 1937 deportation of ethnic Koreans or the deportations of other minorities (and there were many).

Joint Russian Union of Koreans’ representatives accompanied by the cult Russian Korean pop singer Anita Tsoi are presenting a gift to Victor Park, the head of Uzbekistani Korean Cultural Centers Association, in November 2017 – a scene from the 1937 deportation of ethnic Koreans to Central Asia from the Far East (Koryo-saram.ru)

As for South Korea, it has simply turned its overseas ethnic Korean diasporas into a hefty “Trojan horse,” a bargaining chip while dealing with its strategic partners locally and globally.

The question of who should really care about the human rights abuses committed against the ethnic Korean diasporas in Eurasia and Latin America still remains open for discussion.

Victoria Kim previously wrote about the Soviet deportation of Koreans to Uzbekistan (available in parts one, two and three), about General Nam Il, who signed the armistice on behalf of North Korea in 1950, and about her recent journey through North Korea on a passenger train for The Diplomat.