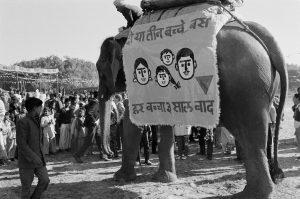

Proposed legislation to control the population of India’s largest state, Uttar Pradesh, is expected to impact women disproportionately.

Unveiling a new population policy for 2021-2030 recently, Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath said that the aim of the policy is to bring down the state’s birth rate to 2.1 per thousand population by 2026 and to 1.9 by 2030. Uttar Pradesh’s current fertility rate is 2.7 per thousand population.

The state is India’s most populous state with almost 200 million people – 16.5 percent of the country’s population.

A few days earlier prior to the unveiling of the new population policy, a draft population control bill was released in the public domain. The bill does two things: one, it incentivizes employees and their spouses to pursue sterilization after having two children with promotion, increments, and education for children; and two, it bars those with more than two children from applying for government jobs, seeking promotions, benefiting from government subsidies, and contesting for local body elections.

This policy is not just punitive but more importantly, it is gender-blind; it could disproportionately impact women, especially poor and marginalized women.

Uttar Pradesh’s women bear the burden of family planning. According to the National Family Health Survey 4 (NFHS-4), 17.3 percent of women in Uttar Pradesh use female sterilization as their family planning method, in comparison to just 0.1 percent of male sterilizations. Female sterilizations are more unsafe and irreversible in comparison to male sterilization or use of contraceptives.

By incentivizing sterilizations as part of the Population Control Bill, the Uttar Pradesh government is putting further onus on women for family planning. It also risks reversing the trend of increasing use of safer methods like condom use. Condoms are the second most popular method for family planning in Uttar Pradesh and twice as prevalent as the national average for India, according to the NFHS-4.

The incentivization of sterilization has come in for criticism from women’s rights organizations, health networks, and academics. “The Bill is geared to control women’s fertility rather than improving women’s health and promoting women’s reproductive rights. The proposed Bill should be deemed unconstitutional since it violates the right to equality,” they have written in a memorandum to the Indian President Ram Nath Kovind.

They added that the population control bill could result in a spike in abandonment of wives and children, particularly daughters, given the wide gap in abortion services. Cases of women who are abandoned, divorced, or killed for giving birth to a daughter, in a state like Uttar Pradesh where son preference remains high, are not hard to find.

A study by bureaucrat Nirmala Buch found that in five Indian states (Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, Odisha, and Rajasthan) where the two-child qualification was implemented in local bodies, sex-selective and unsafe abortions increased, families gave up children for adoption, and men divorced or deserted their spouses to avoid disqualification.

This impact of the two-child norm was also hierarchical, with powerful castes and classes able to circumvent these provisions, while women, particularly those from marginalized castes and classes, were left worse off. Socially backward classes formed 80 percent of the people disqualified from running for local office and nearly half were from lower income brackets.

A study finds that the highest deficits in female births from 2017 to 2030 will occur in Uttar Pradesh, with 2 million missing female births – 28.5 percent of the total female birth deficit during 2017-2030 for the entire country. Introduction of a two-child policy will only exacerbate the problem of sex-selective abortions and female feticide, as evidenced in this study and in the case of China, which saw a rapid increase of female infanticide after the introduction of its one-child policy.

The 2011 Census finds that India already has highly skewed sex ratios with the child sex ratio falling over the decade, from 927 to 919 females for every 1000 males. The proposed policy could skew it further especially in states like Uttar Pradesh where the latest child sex ratio is 902 females for every 1000 males.

Uttar Pradesh is the second Bharatiya Janata Party-ruled state to introduce such a population control measure. Last month, Assam announced plans for a policy that would disqualify families with over two children from government benefits.

Like Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat will be facing crucial assembly elections next year. Its government too has said that it is studying the bill proposed by the Uttar Pradesh government and is weighing its pros and cons. A BJP parliamentarian from Uttar Pradesh, Ravi Kishen, also plans to introduce a similar population control bill in the current Monsoon session of the Parliament.

While fertility rates in Uttar Pradesh have been higher than the national average, they have been falling consistently for the past few years; it has nearly halved from 4.8 percent in 1992-1993 to 2.7 percent in 2015-2016, according to the National Family Health Surveys, raising questions regarding the timing of this harsh policy.

There is no denying that fertility decline in a high population state like Uttar Pradesh is essential for India to meet its population control targets. But this does not have to disproportionately impact women.

Recently, Bihar’s Chief Minister Nitish Kumar said that improving women’s education is a better measure for reducing the fertility rate then population control laws. “When women become more educated and aware, population growth will be reduced,” said Kumar. Other Indian states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh have seen reduction in fertility rates by improving literacy.

Uttar Pradesh also has low family planning coverage compared to the rest of the country. According to one estimate, the state accounts for 25 percent of the total unmet need for family planning in all of India. In 2015-16, one in every six married women in Uttar Pradesh could not access contraception and risked unintended pregnancy. Enhancing access to family planning could help bring down the state’s fertility rate.

More than the proposed punitive population control legislation, improving access to family planning and education for Uttar Pradesh’s women could better help Chief Minister Adityanath “bring the path of happiness and prosperity in the life of every citizen.”