Most would agree that the martial law period in the Philippines from 1972 to 1986 was a dark time, marred by violence, the suspension of basic civil liberties, and unparalleled thievery by those in power. Former dictator Ferdinand Marcos is long gone now; after being deposed by a popular uprising in 1986 he died in exile in Honolulu in 1989. But his feats and his memory continue to polarize Philippine politics almost as much as when he was in power.

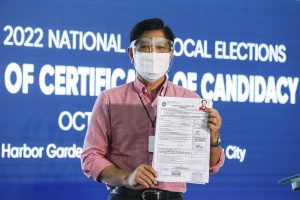

Marcos’ son, Ferdinand Marcos Jr., better known as “Bongbong,” officially announced his candidacy for the upcoming May 2022 presidential election October 5 with clear intentions to revitalize his father’s legacy. Almost half a century since military rule was declared, the Philippines may yet see its instigators rise to power once more. In his announcement, the dictator’s son spoke of bringing back “unifying leadership” to the country, perhaps alluding to his father’s rule, when all were united under the whim of one man.

While the sins of the father do not always mean the son is to blame, Bongbong has made it clear to the public many times that he sees the martial law period as a positive contribution to the trajectory of Philippine society. On a popular talk show last month, Marcos told the host that his father’s tenure carried the Philippines into “the modern world.” The TV appearance was one of many increasingly high-profile stunts designed to plant Bongbong in the public consciousness. Later in the month, he was nominated as the standard-bearer for the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (Movement for a New Society), a political party founded by his father.

Bongbong’s popularity has steadily grown alongside the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte. It helps that the latter mimics the authoritarianism of the former’s father and has amassed many comparisons with the dictator. Duterte and the Marcoses generally have strong political ties between them. The family has made favorable comments toward Duterte even during the early days of his bid for office. Duterte granted Ferdinand Marcos a hero’s burial in Manila in 2016, 27 years after his death and 23 years after his body was brought back to the Philippines. Marcos had been the only president denied such an honor.

Like Father, Like Son?

Bongbong Marcos idolizes his father. At the peak of the family’s far-reaching powers in the mid-1980s, Bongbong served as vice governor, and then governor of their home province, Ilocos Norte. He was also appointed board chairman of the Philippine Communications and Satellite Corporation. He was in his 20s at the time, and while there has never been any categorical or damning evidence as to his role in the regime’s corruption, as part of the family’s inner circle, it’s a safe assumption that he benefited. His mother, Imelda Marcos, was convicted of seven counts of graft in 2018.

The Marcoses accumulated around $658 million during their time in power, according to Supreme Court findings in 2003. There were over 3,200 casualties of the Marcos regime, while over 70,000 dissidents were thrown in jail during Marcos’ reign. The family continues to deny any wrongdoing. The Marcoses and their critics accuse each other of historical revisionism.

Bongbong’s bold claims about his father ushering in modernity is the kind of rhetoric that speaks to a specific set of voters. It sparks debate on whether or not the Philippines was actually economically well off during the Marcos period and, for those who look back with warm nostalgia, it persuades some to think that a degree of violation of human rights may be necessary to achieve progress. This is a narrative not unlike those peddled by many of Duterte’s supporters.

In truth, however, the Philippine GDP dropped dramatically in the last two years of Marcos’ term. Several pet infrastructure projects were abandoned, such as the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant. Moreover, the debt accumulated during the Marcos period, eventually totaling 470 billion Philippine pesos, four times larger than the entire national budget during the last year of his rule. The economy was driven to shambles and the plundering didn’t stop, only helped along with the collapse.

Bongbong has more than just defended his father’s legacy, but built his career on a desire to repeat it. Both father and son were congressmen, then senators, before running for the top post in the country. If Bongbong’s recent public appearances are to any indication, his current platform is one of returning the Philippines to an illusion of its former glories. In a sense, his electoral pitch is “Make the Philippines Great Again.”

Never Again

Opposition forces are wary of a Duterte-Marcos tandem for the upcoming election, whatever shape or form that may take: Bongbong with a Duterte as his running mate, or even the two camps mutually supporting each other’s efforts. At the moment, the landscape of presidential candidates is still unpredictable, with the president himself making surprise turns left and right. First, Duterte said he’d make a run for the vice presidential spot,which in the Philippines is elected separately from the president, retaining his presence in the executive suite like Marcos did. Next, he said he’s retiring from politics, and his ally and long-time aide, Christopher “Bong” Go, will take his place. In a statement, Go said “I intend to continue the great programs and genuine change that began with President Duterte.” Sara Duterte, the president’s daughter and current mayor of Davao City, could be Go’s running mate.

It’s all still up in the air.

Both Go and Sara share the same political drive of the elder Duterte to round up and eliminate all of their political rivals while beefing up the presence of the armed forces in the process.

Renato Reyes Jr., secretary general of the broad opposition umbrella group Bayan (People), said, “The Duterte-Marcos tandem is the gravest, most dangerous threat to the democratic aspirations of the Filipino people. It is intended to cover-up systemic plunder and legitimize gross human rights violations. We cannot let it succeed. We must do all we can to prevent this tandem-of-doom from happening. All democratic forces must come together and exert the greatest effort to prevent a Duterte dynasty or a Marcos restoration in Malacanang Palace. This has become a matter of national survival.”

Whatever the combination, the prospect of both Bongbong and a Duterte-backed candidate making a dash to lord over the country for the next six years can have terrifying consequences for the Philippines. Either the state is thrust into an unwanted martial law throwback, or it faces more of the same creeping authoritarianism, which now isn’t far off from all-out state dominion.