Outside a Shiite shrine in Kabul, four armed Taliban fighters stood guard on a recent Friday as worshippers filed in for weekly prayers. Alongside them was a guard from Afghanistan’s mainly Shiite Hazara minority, an automatic rifle slung over his shoulder.

It was a sign of the strange, new relationship brought by the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan. The Taliban, Sunni hard-liners who for decades targeted the Hazaras as heretics, are now their only protection against a more brutal enemy: the Islamic State group.

Sohrab, the Hazara guard standing watch over the Abul Fazl al-Abbas Shrine, told The Associated Press that he gets along fine with the Taliban guards. “They even pray in the mosque sometimes,” he said, giving only his first name for security reasons.

Not everyone feels so comfortable.

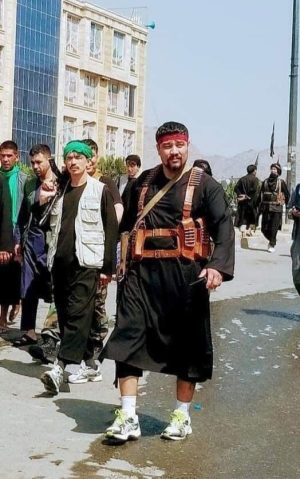

Syed Aqil, a young Hazara visiting the ornate shrine along with his wife and 8-month-old daughter, was disturbed that many of the Taliban still wear their traditional garb — the look of a jihadi insurgent — rather than a police uniform.

“We can’t even tell if they are Taliban or Daesh,” he said, using the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State group.

Since seizing power three months ago, the Taliban have presented themselves as more moderate, compared with their first rule in the late 1990s when they violently repressed the Hazaras and other ethnic groups. Courting international recognition, they vow to protect the Hazaras as a show of their acceptance of the country’s minorities.

But many Hazaras still deeply distrust the insurgents-turned-rulers, who are overwhelmingly ethnic Pashtun, and are convinced they will never accept them as equals in Afghanistan. Hazara community leaders say they have met repeatedly with Taliban leadership, asking to take part in the government, only to be shunned. Hazaras complain individual fighters still discriminate against them and fear it’s only a matter of time before the Taliban revert to repression.

“In comparison to their previous rule, the Taliban are a little better,” said Mohammed Jawad Gawhari, a Hazara cleric who runs an organization helping the poor.

“The problem is that there is not a single law. Every individual Talib is their own law right now,” he said. “So people live in fear of them.”

Some changes from the previous era of Taliban rule are clear. After their August takeover, the Taliban allowed Shiites to perform their religious ceremonies, such as the annual Ashura procession.

The Taliban initially confiscated weapons that Hazaras had used, with permission from the previous government, to guard some of their own mosques in Kabul. But after devastating IS bombings of Shiite mosques in Kandahar and Kunduz provinces in October, the Taliban returned the weapons in most cases, Gawhari and other community leaders said. The Taliban also provide their own fighters as guards for some mosques during Friday prayers.

“We are providing a safe and secure environment for everyone, especially the Hazaras,” Taliban government spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said. “They should be in Afghanistan. Leaving the country is not good for anyone.”

The Hazaras’ turning to Taliban protection shows how terrified the community is of the Islamic State group, which they say aims to exterminate them. In past years, IS has attacked the Hazaras more ruthlessly than the Taliban ever did, unleashing bombings against Hazara schools, hospitals and mosques, killing hundreds.

IS is also a shared enemy. Though they are Sunni hard-liners like the Taliban, IS militants are waging an insurgency, with frequent attacks on Taliban fighters.

Some Hazara leaders see a potential for cooperation. Ahmed Ali al-Rashed, a senior Hazara cleric, praised the Taliban commanders who now run the main police station in Dashti Barchi, the sprawling district of west Kabul dominated by Hazaras.

“If all Taliban were like them, Afghanistan would be like a garden of flowers,” he said.

Others in Dashti Barchi were skeptical the Taliban will ever change.

Marzieh Mohammedi, whose husband was killed five years ago in fighting with the Taliban, said she’s afraid every time she sees them patrolling Dashti Barchi.

“How can they protect us? We can’t trust them. We feel like they are Daesh,” she said.

The differences are partly religious. But also Hazaras, who make up an estimated 10 percent of Afghanistan’s population of nearly 40 million, are ethnically distinct and speak a variant of Farsi rather than Pashtu. They have a long history of being oppressed by the ethnic Pashtun majority, some of whom stereotype them as intruders.

Aqil said that when he tried to go to a police station for a document, the Taliban guard at the gate only spoke Pashtu and impatiently slammed the door in his face. He had to come back later with a Pashtu-speaking colleague.

“This sort of situation makes me lose hope in the future,” he said. “They don’t know us. They are not broadminded to accept other communities. They act as if they are the owners of this country.”

A young Hazara woman, Massoumeh, said four people were killed last month in her part of Dashti Barchi, raising residents’ fears that people with roles in the previous government were targets.

She went with a community delegation led by a local elder to the area’s Taliban police station to discuss security. The only woman in the delegation, she had to wait in the yard while the others met with the district commander, who she said tried to blame the security failings on the local elder. As the delegation left, a guard told them not to bring a woman with them again, she said.

“How can you keep security in Afghanistan if you can’t keep security in our village?” she said.

The 21-year-old Massoumeh was a nurse at Dashti Barchi’s main hospital in 2020 when IS gunmen stormed the maternity ward, killing at least 24 people, mostly mothers who were pregnant or had just given birth — one of the militants’ most horrific attacks.

Since then, she has been too afraid to return to work because of death threats after she spoke about the attack on Afghan TV. Soon after the attack, two militants approached her on a bus late at night, picking her out using a photo on their phone, and pulled a gun on her, warning her not to go back to work, she said. She and her father still get threatening phone calls, she said.

Police under the previous government gave her some protection, she said. But she doesn’t even bother to ask the Taliban police for help.

“Of course not. We are afraid of them,” she said. “No one will come and help us.”

Other events in the Hazaras’ central Afghanistan heartland have raised the community’s concerns. In Daikundi province, Taliban fighters killed 11 Hazara soldiers and two civilians, including a teenage girl, in August, according to Amnesty International. Taliban officials also expelled Hazara families from several Daikundi villages after accusing them of living on land that didn’t belong to them.

After an uproar from Hazaras, further expulsions were halted, Gawhari and other community leaders said.

But so far, the Taliban have rejected repeated requests from the Hazaras for a say in government. Gawhari, the cleric, said a Hazara delegation approached the Taliban and proposed 50 Hazara experts and academics to be brought into the administration. “They were not interested,” he said.

The international community is pressing the Taliban to form a government that reflects Afghanistan’s ethnic, religious and political spectrum, including women. The Taliban’s Cabinet is comprised entirely of men from their own ranks.

Last week, Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi expressed impatience with international demands for inclusivity. “Our current Cabinet fulfils that requirement, we have representatives from all ethnicities,” he told reporters.

The highest level Hazara in the administration is a deputy health minister. Several other Hazaras hold some provincial posts, but they are Hazaras who long ago joined the Taliban insurgency and adopted its hard-line ideology. Few in the Hazara community recognize them.

Ali Akbar Jamshidi, a former parliament member representing Daikundi province, said Hazaras won’t be satisfied with a few local positions and want to be brought into the Cabinet and the intelligence and security services.

The Taliban, he said, are running a government “that acts like a warlord who has seized everything.”

“Physical security is not enough. We need psychological security as well, feeling like we are part of this government and it is part of us,” he said. “The Taliban can benefit from us. They have the opportunity to form a government for the future, but they are not taking this opportunity.”

Abdul Qahhar Afghan contributed.