New Zealand’s hosting of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Leaders’ Week is about to begin. Were it not for COVID-19, the week would be a once-in-a-generation, high-profile opportunity for New Zealand to showcase itself to 20 visiting leaders from around the Pacific Rim.

APEC’s 21 member economies account for 38 percent of the world’s population and over 60 percent of its GDP. China, Japan, Russia, and the United States are among the group’s political and economic heavyweights.

New Zealand’s last hosting of APEC, in September 1999, was stunningly successful. The success had little to do with the substance of what the leaders agreed in their final declaration, however. Rather, it stemmed from the optics of the 21 leaders mingling together in Auckland – which had never previously hosted a summit on the same scale.

The event was one of the first major gatherings attended by Vladimir Putin, following his appointment as Russia’s prime minister the previous month. Moreover, APEC 1999 was a chance for the United States and China to address differences over China’s bid to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) and resolve other tensions.

Photo opportunities also abounded. These came both at the APEC summit itself and at three state visits held immediately afterwards for the Chinese, South Korean, and U.S. presidents. It is difficult to overstate the significance of these visits.

Jiang Zemin’s visit was the first to New Zealand by a Chinese president. His presence undoubtedly helped Wellington to forge closer ties with Beijing. New Zealand was a strong supporter of China’s bid to join the WTO, which was finally approved in 2001. The growing ties culminated in the signing of a free trade agreement between China and New Zealand in 2008.

Meanwhile, Bill Clinton’s visit was the first by a sitting U.S. president to New Zealand since Lyndon Johnson’s brief visit to Wellington in 1966.

More broadly, APEC 1999 marked the beginnings of a more confident, free trade-focused pathway for New Zealand’s foreign policy, which continues to this day.

For Wellington, one of the biggest legacies of APEC 1999 was the agreement on the sidelines by Prime Minister Jenny Shipley and her Singaporean counterpart, Goh Chok Tong, to launch free trade negotiations between the two countries. Talks began soon after APEC and an agreement was signed in 2000. It was Singapore’s very first bilateral free trade agreement (FTA) and only New Zealand’s second, after a long-standing deal with Australia.

At the time, the negotiations seemed to be a way for New Zealand to hedge its bets. Much of the APEC 1999 leaders’ declaration focused on supporting the WTO negotiations that were set to begin later that year. Essentially, by testing the waters and taking the FTA route with Singapore, New Zealand was giving itself a back-up option – a prudent move, given later WTO failures.

Later APEC meetings continued to play a pivotal role in New Zealand’s strategy. At the 2002 APEC summit in Mexico, New Zealand and Singapore began talks with Chile to expand the agreement into a three-way deal. Brunei, another APEC member, subsequently joined the agreement, which became the P4. In turn, the P4 became the genesis for what turned into today’s Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, or CPTPP.

Fast-forward to 2021 and the APEC story is very different. A spirit of post-Cold War optimism and cooperation has long since dissipated. The China-U.S. tensions that were amicably resolved at APEC in 1999 seem minor by today’s standards.

The virtual format for this year’s meetings is also having an impact. New Zealand took the decision to shift all APEC events online in June 2020. Given the uncertainties over COVID-19 and the scale of APEC, this was the right decision, but it brings both opportunities and costs.

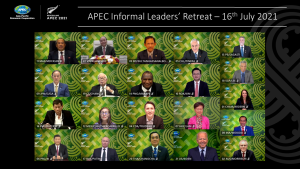

Around 1,000 hours of virtual meetings have been held since the beginning of New Zealand’s APEC year in December 2020. These meetings included July’s surprise extra APEC leaders’ summit – arranged at short-notice and focused on the COVID-19 response – as well as many other events for ministers and officials.

Some useful outcomes have resulted from these meeting, such as undertakings among APEC economies to speed up vaccine distribution by reducing tariff and other barriers for designated medical supplies such as syringes.

But the lack of in-person meetings means that it is difficult – if not impossible – for leaders to forge or develop any real rapport with one another. Providing such a varied group of leaders with a venue to build relationships has always been APEC’s strong suit.

Growing tensions, especially between the United States and China, mean that the need for de-escalation has never been greater. Tensions between China and Taiwan – and between China and the U.S. – only continue to build. Chinese military activity near Taiwan is increasing. For its part, Taipei recently confirmed for the first time that U.S. troops were located on its soil. And this week, a U.S. Defense Department report on the state of the Chinese military suggested that Beijing was building its nuclear weapons stockpile far more rapidly than previously thought.

The fact that China and Taiwan are both APEC members – a rare example of the pair working together – provides an opportunity for dialogue that simply does not exist elsewhere.

However, Chinese President Xi Jinping did not attend this month’s in-person G-20 or COP26 summits. It is unlikely that he would have attended a physical APEC summit either, even if New Zealand had chosen to host an in-person meeting.

It remains to be seen what the outcome of this year’s online APEC leaders’ meeting will be. Expectations of success for a summit by video call will always be low, but that might not be such a bad thing.

APEC is flying virtually under the radar.

This article was originally published by the Democracy Project, which aims to enhance New Zealand democracy and public life by promoting critical thinking, analysis, debate, and engagement on politics and society.