Away from the shoreline crammed with vast swathes of shipping containers and gantry cranes – with which the town has become synonymous – tens of thousands of low-income families make homes in the urban district of Kwai Chung, in the New Territories of Hong Kong. Those still in line for public housing mostly dwell in often squalid, windowless, poorly ventilated subdivided flats in aged apartment buildings.

Siu Fung (a pseudonym used on request), a mother of three in her early 40s, resides with her family in one such flat, located near the northwestern edge of the Kam Shan Country Park. The only perk, she said, is its access to a small, open roof terrace, where she grows a small assortment of fruits and routinely handwashes and line-dries her family’s laundry.

Also frequenting the terrace are swarms of “black, big” mosquitoes capable of leaving irritating bites all over the residents’ arms and legs “in mere minutes.” The culprit, she believes, is the building’s dilapidated drainage pipes, which her landlord has little interest in fixing. As a result, stale water gathers in and around the terrace, creating breeding sites for mosquitoes such as Aedes albopictus (colloquially called Asian tiger mosquitoes), the primary vector of dengue fever in Hong Kong.

At night, mosquitoes roam around the family’s rooms while they sleep. None of the repelling incenses and balms work, she said; hanging a mosquito net over their beds isn’t feasible either. She refrains from using repellent spray inside the flat for fear of worsening her 7-year-old son’s symptoms of ADHD – a condition thought to be more likely among children living in subdivided flats owing to the lack of stimuli in their environment.

The roof terrace adjoining Siu Fung’s subdivided flat in Kwai Chung. Photo by Crystal Chow.

In Heat and Poverty They Thrive

The link between urbanization, poverty, and the risk of mosquito-borne diseases is well established. A study from the United States, for example, finds that residents in low-income areas in Baltimore with high levels of residential abandonment, rife with rain-filled litter and overgrown foliage, are more vulnerable to the risk of diseases carried by Asian tiger mosquitoes (Zika virus included) than those from better-off neighborhoods.

Adding to this mounting burden is the way climate change drives the transmission of diseases. The urban poor in Asia is set to bear the brunt of worsening health impacts of climate change; a study estimates that by 2080, Asian tiger mosquitoes alone could expose over 41 million people across East Asia to disease transmission risks for the first time.

Like most families cramped in small living units, Siu Fung can tell the summers are getting warmer and longer. A recent survey from Oxfam Hong Kong finds nearly 70 percent of subdivided flat tenants are already affected by the extreme heat; half of the flats recorded higher temperatures indoors than outside. And with heat and humidity come the mosquitoes.

“The period around August to September is usually the worst,” she said. “It does get better if we have the air-conditioning on.” But that isn’t an easy option: Running the air conditioner regularly would mean a 15 percent to 20 percent rise in their monthly cost for electricity, amounting to more than a quarter of their rent – which costs around US$835.

While dengue fever is not endemic in Hong Kong, a local outbreak in 2018 with a total of 29 recorded cases was enough to cause alarm among the city’s public health experts. “Dengue infection is on the rise [including in] our neighboring regions where the disease is endemic,” said Dr. Kevin Hung, an assistant professor in emergency medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK).

“Who is to say it won’t become endemic too in Hong Kong?”

Hong Kong’s Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD) currently deploys a city-wide surveillance program to monitor the distribution of Asian tiger mosquitoes. Gravidtraps (formerly ovidtraps) are placed at selected sites to detect their larval breeding rate. Two indices are updated monthly to indicate the scale of the mosquito’s distribution at district and city levels. Meanwhile, surveillance practices for Culex tritaeniorhynchus, which could transmit the Japanese encephalitis virus, is carried out separately in targeted districts.

After the outbreak in 2018, Hung and a group of researchers embarked on a survey to gauge prevention awareness; They found the ovitrap index and self-reported mosquito bites at home did not correlate significantly. Could dengue risk in certain areas be higher than what the index implies?

When Data Falls Short

Despite having followed the relevant recommendations from WHO, the dengue surveillance’s effectiveness has been called into question. Its geographic coverage was deemed “incomprehensive” by the city’s own ombudsman earlier this year. But other attempts had been made.

Back in 2019, FEHD briefly explored introducing AI-enabled surveillance technology that could track images of mosquito larvae. The plan was later shelved, however, due to concerns over its performance constraints and cost-effectiveness, as explained by Ming-wai Lee, the FEHD’s pest control officer-in-charge, in a written response to The Diplomat.

Across the straits in Taiwan, a bottom-up approach might have been conducive to more transparent management of vector surveillance data. After his wife fell ill with dengue fever amid one of Taiwan’s worst outbreaks in 2015, Finjon Kiang, a programmer affiliated with the open data advocacy network g0v (pronounced “gov-zero”) felt compelled to look for community-level information in his hometown of Tainan, and repurpose them into an online map that would be accessible and visually intuitive to people who may not be as technologically adept.

Using the data supplied in spreadsheet format, Kiang created the Tainan Dengue Map and Dengue Vector Index Map on his GitHub page. A slew of media interest soon followed, and people from the local disease control authority got in touch.

“At that time, some local government units were still relying on hand-written documents for reporting dengue cases,” he explained via Zoom. It meant someone higher up in the command chain had to digitalize these documents through “faxing or scanning” before updating the information into a database.

Today, Taiwan’s disease control strategy is arguably one of the region’s most comprehensive. But Kiang hesitates to take the credit. “Perhaps I just happened to embark on something someone else was already doing,” he said. Initiatives such as his sometimes present their own challenges. “For a crowdsourcing initiative to be successful, the data you ask volunteers to collect has to be simple enough to understand and operate,” he explained. “But if you are looking at, say, how dengue is spreading through the open sewage systems, that’s when you have to design a user-friendly interface for data collection. And that’s where expert knowledge becomes crucial.”

Though the climate crisis and its implications to public health are increasingly weighing on experts, the lack of actionable data remains a stumbling block.

It can be attributed to the issue’s cross-disciplinary nature, which creates a “conceptual gap,” as observed by Janice Ho, a postdoctoral researcher focusing on the effects of climate change on physical health. “Even with all the momentum for climate action, health barely shows up on the agenda,” said Ho, “but health is the first thing that you experience… its impact could be immediate.”

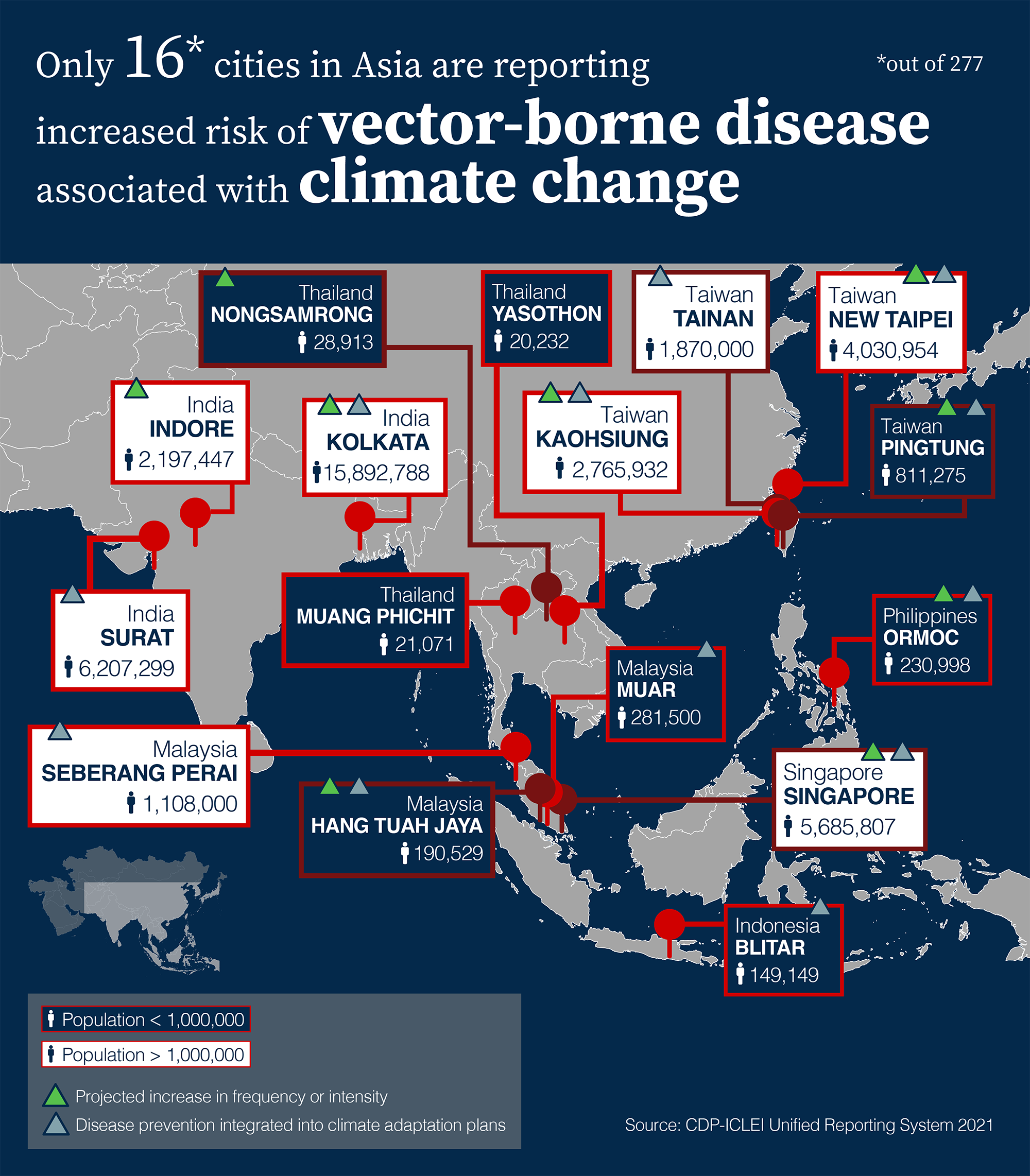

The Asian cities currently reporting the risks of mosquito-borne disease in relation to climate change. Source: CDP-ICLEI Unified Reporting System 2021. Graphics by Jobie Yip.

Bridging Silos

To date, out of the 277 cities in Asia that have reported publicly to CDP, a global environmental disclosure platform, only 16 are identifying increased risks of mosquito-borne diseases associated with climate change. Some cities have stepped up further by integrating disease prevention efforts into their climate adaption plans, including several cities from Taiwan, as well as India and Southeast Asia, where dengue is endemic. Hong Kong isn’t among them.

In a bid to rein in mosquito breeding, a novel sterilization technique – involving the release of male mosquitoes infected with a bacteria called Wolbachia – has emerged as a potential solution. It has, for instance, been recently adopted by Singapore as a national strategy to suppress Aedes aegypti (Yellow fever mosquitoes), another common vector in Asia.

Local experts, however, aren’t convinced that sterilization is necessary. “Its benefits in certain regions with high incidences of the deadly mosquito-borne disease are probably significant,” said Hsiang-yu Yuan, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the City University of Hong Kong. But for “sub-tropical region like Hong Kong and Taiwan” pursuing sterilization could risk upsetting “the balance of our ecosystems.”

“I don’t think [it] makes any difference… Biological control has been tried for decades with little success,” asserted Dr. Tze-wai Wong, an environmental epidemiologist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who has experience in infectious disease control dating from the late 1970s. Working on improving our existing vector control and prevention strategy might be more effective, he contended.

“We need a system to predict when and where the risk is going to rise, so we can target certain areas more precisely,” explained Yuan, who has led two respective studies modelling climate variables and the incidence of dengue fever in Hong Kong and southern Taiwan. “The better way is to have an international collaboration to monitor patterns of vectors across Hong Kong and our neighboring countries like Vietnam, Thailand, China, and even Japan.”

To facilitate better data gathering and sharing, Yuan calls for a “standardized platform” open to governments across the region, an initiative akin to the European Surveillance System that collects standardized, comparable information on communicable diseases.

“Hong Kong has a well-functioning emergency response system,” Hung said. “What we need to build on it is a more proactive, systematic approach to assess and address risks and vulnerability in tandem, that doesn’t just look at one particular disease or fall on a single government body.”

This story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.