Ancient Mogilev, a former city of the medieval Duchy of Lithuania and now part of Belarus close to the border with Russia, cradled along the River Dnieper, is a most unlikely spot for an interview about forced prison labor in China. But this is the home to which Dima Siakatsky returned after his release from Shanghai’s Qingpu Prison, where he witnessed foreign prisoners being coerced into labor, packaging goods for foreign and Chinese brands.

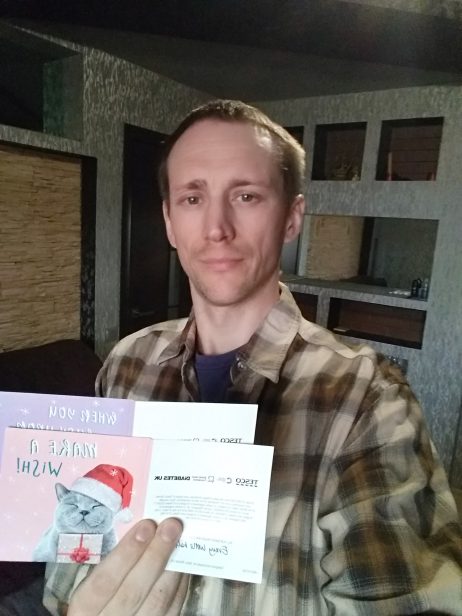

China’s foreign prisoners come from all over the planet. I was interviewing Siakatsky by video at his home in Mogilev several months after his return, when he pulled out a handful of Christmas cards made for the Tesco supermarket chain and waved them at the screen. “Here is the evidence that prisoners at Qingpu Prison were packaging these cards,” he said. “I kept some of the cards and smuggled them out with me as proof.”

During our interview, Siakatsky recounted that on Christmas Day in the prison in 2019, cheers broke out when he got into a fight with another prisoner and dumped a plate of hot food on the other man’s head. Guards rushed to break up the fracas, and Siakatsky, who was deemed to have provoked the fight, was hauled off to spend 80 days in solitary confinement.

Siakatsky had attacked an inmate who was cooperating in the prison’s attempt to cover up the forced labor scandal that was inadvertently exposed when a young English girl found a message from prisoners at Qingpu scrawled in a Tesco Christmas Card.

In 2019, Florence Widdicombe, then a 6-year-old London schoolgirl, discovered a despairing message from Shanghai prisoners forced to pack boxes of Christmas charity cards bound for British supermarkets.

Her discovery made headlines around the world. I wrote up the story for the Sunday Times and followed it up with another one about the prisoners packaging Quaker oatmeal.

There were quick denials by Chinese media and Beijing’s foreign ministry at the time, and I came under a vicious personal attack in a 30-minute CGTN program assassinating my character.

Over the past two years I have gradually pieced together the reaction inside the jail after my Sunday Times story was published on December 22, 2019. Several of the prisoners involved have been released from Qingpu over the past year and have described the panic that erupted after Chinese authorities learned of Florence’s find.

When the story came out, a pair of new foreign prisoners who hadn’t been involved in the smuggled messaging were persuaded to deny everything for visiting Chinese state media television cameras. Emotions in the foreign prisoners’ “Brigade Eight” cell block boiled over.

“The guards arranged for the TV crews to film tables stacked with good food to present the impression the prisoners were treated well,” said Siakatsky, who is a furniture trader.

As one of the prisoners who had packaged the cards, Siakatsky secreted away several as evidence and took them with him when he was released last summer after serving 40 months for allegedly carrying a fake credit card. During his video interview with me, he produced them for the camera. They were identical to the Tesco cards that Florence’s father, Ben, handed to me two years ago.

Dima Siakatsky holding Tesco Christmas cards, smuggled out from Qingpu prison. Screenshot of an online video call by Dima Siakatsky.

He said the prison governor, Li Qiang, went on camera and denied the prison had any involvement with the cards.

“This was a blatant lie,” Siakatsky proclaimed. “The Christmas cards were packed exactly in Brigade Eight by the hands of prisoners in the same room where they eat and spend their time. In this room there were stands with information about who and how many cards and other products each prisoner made.

“Then the officers, and some prisoners under orders, began urgently to remove all evidence that prisoners worked in the brigade. By evening it became clear why.”

Siakatsky said the prosecutors based in the prison came to interrogate two prisoners who had committed genuinely serious crimes, and persuaded them to talk to the TV crews. “I told them that I also wanted to testify about the Christmas cards and that I had proof, holding up some of the cards. To which they replied that they did not need my testimony and evidence,” he said.

“At dinner time, reporters and senior officers of the Prison Bureau arrived at the brigade. Jailers were posted to prevent me from seeing what was happening at first. The guards knew very well that I might intervene. So I could only see the journalists through a window. I saw the police look at the fake dinner on the tables and nod their heads and grin in approval,” Siakatsky said.

“I went up to the officers, took out some cards, raised my hand and said that the Christmas cards were made here and I want to testify. The next moment captains Wei and Zhao took the cards and pushed me out of the room. I said that the governor had lied on TV,” Siakatsky continued.

“The next day I saw a report on the Chinese channel that they had filmed the day before. One prisoner, an Italian pedophile, said that in this prison there was a good attitude towards prisoners and good food. This was also a complete lie.”

Siakatsky was outraged that learned that an Italian prisoner convicted of sex crimes was apparently seeking to curry favor with guards by denying the practice of forced labor within the prison. “So during dinner, I took my dinner plate and poured it over his head. Captain Wei was on duty that day. He handcuffed me, applied force to me and sent me to solitary where I spent 80 days.” This was the longest time a foreign prisoner in Qingpu had ever spent in solitary.

“The statement that the cards were not produced in prison and the demonstration of good food seemed to me complete hypocrisy,” Siakatsky said.

The 2019 Christmas Card Discovery

Campaigners and critics have long claimed that Chinese jails coerce inmates into “slave labor” on a wide range of both foreign and domestic products. I personally witnessed coerced labor by prisoners packaging foreign-branded wares at Qingpu when I was held there in 2014-2015 in my own widely-publicized arbitrary imprisonment. Florence Widdicombe’s shocking discovery provided unmistakable evidence that China had found a way to sidestep international scrutiny of its manufacturing and packaging supply chains.

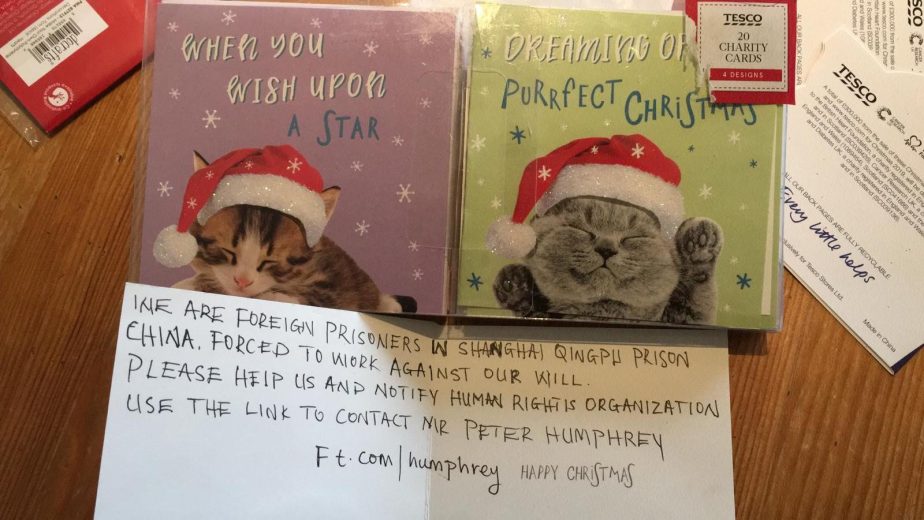

“We are foreign prisoners in Shanghai Qingpu prison China,” read the message written in capital letters inside a Christmas card purchased by the Widdicombe family. “Forced to work against our will. Please help and notify human rights organization.” The message also urged the reader to contact me personally.

The message Florence Widdicombe found inside a purchased Christmas card in December 2019. Photo by Ben Widdicombe.

Tesco terminated its dealings with the factory that had made the cards and insisted that “we do not allow the use of prison labor in our supply chain.” Inside Qingpu’s Brigade Eight, which houses more than 300 foreign prisoners, officers were panicking.

“There was chaos, the prison officials were shaking with fear,” recalled Romeo Papava, another former inmate, whom I interviewed by video from his home in Tbilisi, Georgia, after his release from Qingpu last year.

Captain Zhao Minfeng, the officer in charge of prison labor in Brigade Eight, was demoted for allowing the message incident to occur. Captain Wei Wei, an officer who prisoners say abused and beat prisoners – Wei was my tormentor during my own time at Qingpu – led a search to try to unmask the message writers but failed. Even so, he was rewarded for his heavy-handedness with a promotion and is now in charge of the brigade, Papava said.

The prison blocked television news broadcasts for two days, but word quickly spread about the secret message in the Christmas card and the fact that the authorities were denying everything.

Anatomy of a Cover-up

The 2019 scandal ignited feverish activity by the Chinese propaganda apparatus to cover up and deny the naked truth. “It is such an imaginative story, the opposite of efforts to reform prisoners,” prison governor Li Qiang told Communist Party (CCP)-controlled Central Chinese Television (CCTV).

“Prisoners only work voluntarily,” Li said. “The prisoners get reasonable payment for their work.” By this he was referring to a paltry maximum of 120 renminbi (under $20) for one month of full-time work.

A broadcast on Xinhua TV labeled the story “fake news” and said it had been “denied by foreign prisoners in Qingpu.” “An Italian and a Burundian inmate said they were not forced to do anything,” it reported. The owner of the Christmas card factory said the story was “fabricated” and that he did not even know the contact details of the prison.

Another broadcast from an outlet of Shanghai United Media Group showed foreign prisoners acting in a drama, accessing video lessons, playing chess, writing, and making handicrafts. It showed the Italian and Burundian pretending to do Chinese calligraphy. This is quite remarkable, considering they had only been in China for a short time and did not know the Chinese language. The Italian even claimed he was studying the saxophone. But prisoners say such activities are rare and are only for a privileged few prisoners who collaborate with their captors.

CCTV also aired a clip with the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang denying the story and alleged that I had “fabricated a farce” in my reporting. Geng even bizarrely denied the existence of labor at all in the Chinese prison system, even though it is actually written into China’s prison law.

The Cover-up as Seen From Inside the Prison

“On Christmas Day they sent Chinese TV to the prison to do a cover-up and to show how wonderful our life was in there,” said Papava, an import-export trader who served a four-and-a-half year sentence for an alleged theft. “Two prisoners – an Italian rapist and a Burundian car thief – were put in front of the cameras to lie. They said exactly what they were told to say.”

Papava said the two men were rewarded with “merit points” that gave them extra prison privileges.

In this screenshot from a video report by The Paper, prisoners from Italy and Burundi practice calligraphy. The text reads, in Chinese, “We can also study Chinese history, ancient Chinese poetry, and Chinese language.” Other prisoners say the interviews and activities that appeared on camera in Chinese state media reports about Qingpu Prison were elaborately staged.

Released prisoners, including one of the authors of the messages, have told me the officers never succeeded in finding the authors of the letter Florence discovered. Their identities were disguised in my original Sunday Times piece. One author remains in the prison, and I have withheld his identity to protect him.

In the aftermath of the Tesco story, “all work stopped because they stopped delivering raw materials,” Siakatsky said. Prisoners were later pressed to sign a “voluntary consent” form to show that they participated willingly in prison labor. Signing the forms became part of the formula that earned prisoners sentence reduction points.

“If you want to leave prison earlier … you have to be sure to work,” said Siakatsky.

Prisoners in both foreign and Chinese cell blocks there were also afterwards forbidden to take pens into work areas “so that no one could write a message and hide it inside a product,” said Siakatsky. While work on commercial products resumed for Chinese prisoners, foreign inmates were, for a time, restricted to goods that were seemingly bound for domestic markets.

Recently released prisoners said they worked last year on clothing for Hotwind, a Chinese streetwear fashion brand; others worked on prison guard uniforms and the lettering on computer keyboards that bore no brand names while they handled them. A Nigerian named Thursday, freed last July, said prison work on commercial products was continuing when he came home.

“I was there on that Christmas when it happened. They denied we were working on the Tesco Christmas cards. We were so upset when these two prisoners lied to Chinese media. They were trying to control China’s image to the world,” said Thursday, now a real estate broker in Nigeria’s Delta. “They stopped the labor for some months and then started again. They were still doing it when I was released.”

Forced Prison Labor: The Norm, Not the Exception

Forced labor is in fact the norm across the Chinese prison system. When I was in the pretrial Shanghai Detention Center in 2013-2014 they had just abolished manufacturing labor there, ending the production of Christmas lights for export. But I witnessed prison labor in Qingpu. I saw thousands of Chinese prisoners march daily across the campus in military style to the prison factory, which made textiles for famous labels including Adidas and Nike and electronic parts.

In Brigade Eight I personally witnessed the making of packaging materials for H&M, C&A, and 3M, which I wrote about in 2018. All these companies denied any knowledge of this activity and I am inclined to believe them, especially as H&M was my own former consultancy client.

Today, prisoners have told me that if you refuse to do this work, you will not be considered for sentence reduction and early release, and you will lose other privileges such as prison shopping and family telephone calls. So most foreign prisoners reluctantly do it, especially as anyone who refuses becomes a target for abuse.

It is also well-known that interned Uyghurs in Xinjiang have been forced to labor on cotton farms and in textile factories over the past few years as part of the CCP’s genocidal policies in that region. But the practice is not unique to the Uyghurs. Forced labor is in fact pervasive throughout the entire Chinese prison system, and is present in all Chinese incarceration facilities, which hold many millions of prisoners.

The “message-in-a-bottle” tactic is used from time to time to seek foreign help, as it was in the Tesco incident. But it carries high risks. Some years ago a Chinese prisoner in a labor camp at a place called Masanjia smuggled out a letter inside Halloween decorations that ended up in a Wal-Mart store in Seattle and became a sensation. After his release, he moved to Indonesia where he was killed. There are suspicions he was murdered by Chinese agents for blowing the whistle.

Every Chinese prison relies on income from commercial manufacturing contracts to fund itself, and officers earn bonuses for bringing in business and reaching financial targets. The senior officer in my Brigade Eight earned a luxury holiday in Fiji while I was there. Forced labor is embedded in the prison system. China’s prison network is an enterprise and an industry.

The Christmas Card Incident: Echoes Today

Florence Widdicombe still remembers the sense of bewilderment she felt when she pulled a card from the box her parents had bought from their local Tesco branch, and was annoyed to discover that someone had “already written in it.”

Two years later, with COVID-19 restrictions easing in England, I visited the Widdicombes’ south London home before Christmas for a sandwich lunch and met Florence for the first time. I asked her how she felt about the viral media attention that she got in 2019.

“I didn’t really understand why it was so important,” she told me with a little grin. “My teachers all knew about it. My teacher said I did a good thing.”

Her father Ben, a civil servant who specialized in criminology, realized at once what his daughter had found. The impact from her discovery is still being felt in Qingpu Prison to this day.

While finishing off this report, I received a handwritten document from a foreign prisoner that was smuggled out of Qingpu. The document, titled “The Black Curtain,” is a protest letter covering a wide range of topics, including forced labor and the Christmas card episode.

“Not only was there forced labor, but labor performance was interlaced with inmate shopping grades and most importantly your sentence remission and commutation,” the writer complained. ”In plain language it means that if you do not perform your labor, your remission and commutation of sentence would be impossible.”

He described the scene on that Christmas Day and confirmed Siakatsky’s starring role in the protest against the cover-up. Graciously, he exonerated prison governor Li Qiang by saying, “don’t blame it on Li, he is just one of thousands of puppet officers molded from the production line of the Chinese Communist Party.”

He ended the topic with an appeal: “We hope the international human rights organizations Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Interights, the U.N. High Commission, seek more aggressive actions against China.”

For my original report in 2019 I traced and interviewed a dozen ex-prisoners on five continents who had been released from Qingpu that year and combined their narratives with information buried in letters sent to me by prisoners still in Qingpu. For the current report, I interviewed prisoners who were released in 2020 and 2021. Not all of them have been named in this story. I anticipate further prisoner releases and updates in 2022.