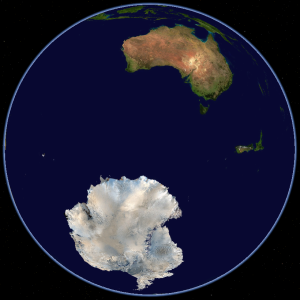

The Antarctic Treaty System has governed affairs in Antarctica since 1961. But it is now struggling under the weight of strategic power competition and new threats to Antarctica’s unique ecosystems. Through gaps in governance frameworks, states are exploiting the treaty to pursue national interests. This article examines how strategic power competition is affecting Antarctica and how Australia, as a claimant to 42 percent of East Antarctica, might seek to better protect it.

Antarctica offers great treasures in natural resources, fishing stocks, bioprospecting opportunities, climate science analysis, and hydrocarbons, with potential reserves of between 300 and 500 billion tonnes of natural gas on the continent and potentially 135 billion tonnes of oil in the Southern Ocean. Article 1 of the Antarctic Treaty declares that use of Antarctica is reserved for scientific observation and investigation – for peaceful purposes only. Article 1, however, is under siege.

Despite the treaty suspending the claims of the seven original claimants (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the U.K.), the United States and then-Soviet Union (as additional, non-claimant, original signatories) exercised the right under the treaty to stake a claim at a later stage. In effect, the treaty froze the issue of territorial sovereignty.

The 90th anniversary of the signing of the Antarctic Treaty in 2049 will follow a 2048 review milestone set for its ban on mining under the Madrid Protocol, which supports the Treaty. Although still some years away, it is right now that the great powers are refocusing their attention on achieving long-term strategic objectives by alternate means. What could change between now and the 2048 review? As stakeholders with voting rights on continental governance, the consultative parties to the treaty might decide to keep its environmental protocol and continue to prohibit mining and militarization – or they might not.

Australia’s 2017 foreign policy white paper emphasizes Indo-Pacific competition, a focus accentuated with the announcement of the AUKUS pact in September. The white paper omitted any mention of challenges in Antarctica. But China’s disregard of the 2016 arbitral tribunal ruling on its South China Sea claims, coupled with its intense competition for resource access and assertive actions in international governance forums, suggests that a wait-and-see approach in Antarctica is high-risk. Existing legal frameworks do not deter major states from acting to secure their own strategic interests, and Australia can’t afford to be naive about its geopolitical context.

China’s Role in Antarctica

Since the establishment of its first Antarctic research station, the Great Wall, in 1985, China has expanded its presence on the continent. Three of the country’s four research stations are based within Australia’s claimed Antarctic Territory, and a fifth is under construction on Inexpressible Island in the Ross Sea. China’s emergence as a polar power includes substantial investment in icebreakers and continental airstrips to provide year-round access.

The Chinese government’s strategic approach to Antarctica is at the level of national security policy. Official documentation incorporates Antarctica and the Southern Ocean into the state’s expanded conception of domains for influence and dominance, beyond the Indo-Pacific. Beijing recognizes no existing claims to the continent and pursues a strategy that maximizes its own national interests there. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has explicitly characterized the polar regions as a “new strategic frontier” and even included them in its latest Five-Year Plan. The CCP seeks to affirm China’s international legitimacy on the continent on the one hand and maximize domestic support for Chinese Antarctic activities on the other.

China thus has “two voices” targeting separate audiences. Externally, China portrays itself as conforming to the treaty system’s institutions with a primary interest in science. Beijing has accused Antarctic forums of being a “rich man’s club” dominated by the United States, claiming that others are portrayed as “second-class citizens.” This ignores the fact that China has equal voting rights as a consultative party and Russia is a long-term “club” member. The CCP narrative is that China has been denied its rightful place in the international order – and in Antarctic governance.

Domestically, President Xi Jinping’s November 2014 speech, given aboard the Xue Long icebreaker then docked in Hobart, declared that China wanted “to become a polar great power.” China then asserted its “right” to polar leadership in 2015 through its national security law, emphasizing the state’s interests in “new frontiers,” including Antarctica and the Arctic, among others. By listing these domains in a security context, China laid a domestic legal foundation to protect its potential future rights in them. Senior Chinese military leaders have also used Antarctica’s “global commons” status to assert China’s entitlement to Antarctic interests.

Science is deployed as a narrative tool to legitimize China’s expanding presence on the continent. A vital part of this claim stresses the importance of climate change research and the need for cooperation from all powers on this front. The polar regions are fundamental to this effort. At the same time, however, Chinese scientific and academic institutions participating in Antarctic science are essentially controlled by the CCP and integrated with China’s civil-military complex.

Xi has explicitly stated that China’s scientists should have the “correct political inclination” and be “imbued with patriotic feelings.” Chinese influence in Antarctic forums reinforces the broader Chinese narrative of its natural right to leadership in international governance. On top of this, the People’s Liberation Army has for some time highlighted the likelihood of polar regions being spaces for “new geopolitical conflict.”

New Zealand China expert Anne-Marie Brady’s research has highlighted China’s Antarctic mapping of the Southern Ocean seabed for future shipping and/or submarine movement. China has linked the polar regions to the Belt and Road Initiative in building a “blue economic passage” to secure its national interests and to “build China into a maritime powerhouse.” Antarctica and the Southern Ocean represent an extension of Beijing’s maritime economic objectives and its drive to access resources and secure associated trade routes and set the conditions for “dual-use” capabilities to effectively control the region.

China’s failure to comply with Antarctic inspection requirements weakens the treaty’s original intent, with poor compliance encouraging militarization below the detection threshold. The implications for Australia would be stark if competition with the U.S. and/or Australia escalated and China ramped up its military presence in Antarctica.

Strategic Competition in Antarctica

Competition on the continent has always involved other players. The United States was pivotal in brokering the Antarctic Treaty and (along with the USSR) was able to deny sovereignty to other states. U.S. policy reinforces the commitment to use Antarctica only for peaceful purposes and free access for science. However, the U.S. “recognizes no foreign territorial claims” and “reserves the right to participate in any future uses of the region.”

The United States is now seeking an enhanced physical presence, with a 2020 presidential memorandum focusing on new “polar security” icebreakers. The Biden administration has not reversed this focus. Meanwhile, how the U.S. contributes to environmental protection in Antarctica in both the near and longer terms will be vital.

Despite the historical relationship and close alliance between Washington and Canberra, the United States has consistently refuted Australia’s territorial claim in Antarctica and reserved its right (along with Russia) to make a future claim. More recently, though, the U.S. has demonstrated actions that may prioritize collective over unilateral interests, supporting the treaty and reaffirming its commitment to prohibitions on mineral resource exploitation. As both competition and cooperation with China continue, for example, on climate change, the U.S. may see merit in ensuring Antarctica’s hydrocarbons and minerals remain off limits for exploitation.

Australia is well positioned to pursue cooperative ventures reinforcing its historic Antarctic position by working closely with allies and treaty members to preserve the treaty’s peaceful and scientific-research intent and to establish firm compliance measures within the treaty system to address gaps that leave Antarctica open to exploitation and its Treaty System ever more vulnerable.