The stakes for Chinese Olympians have never been higher than at Beijing 2022. Though Chinese President Xi Jinping states he “does not care” how many gold medals China wins at the Winter Olympic Games, behind the scenes, these athletes face enormous pressures. The burden to meet China’s Olympic goals of becoming a “winter sports powerhouse” and the ever-present need to cultivate national pride among the Chinese populace has turned Beijing 2022 into a serious geopolitical event amid an international backlash.

“The Olympics are revealing a lot right now,” Michael Sobolik, an Indo-Pacific Studies fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council, told The Diplomat. “It’s revealing the party doesn’t feel they need to apologize or explain themselves to anyone and have the help of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to take that posture.”

Equally revealing is the plight of Chinese athletes caught in the crossfire of great power politics. As human rights concerns and diplomatic boycotts swirl around Beijing 2022, athletes have an even more intense routine than any athletic feat ahead of them: They must simultaneously navigate virulent online nationalism and corporate sponsor objectives, and avoid the increasingly intense political fray surrounding the Games – all while going for gold.

Appeasing China’s netizens can have serious financial implications for athletes. Yang Qian, an air rifle Olympic gold medalist, wore a signature yellow duck pin during her events at Tokyo 2020 that sparked a consumer craze domestically. Her profile has since won her partnerships with Western brands like Estée Lauder.

Even Olympians who don’t win gold can get paid. Su Bingtian, a sixth-place finisher at the 100m final at Tokyo 2020, earned the moniker “pride of China” and as a result of his performance was christened as a brand ambassador for nine Chinese brands, including consumer electronics giant Xiaomi.

Chinese athletes often hail from rough-and-tumble backgrounds and sacrifice traditional educational opportunities to compete in the athletic system. As such, Olympic stardom represents their best chance at a comfortable life. Quan Hongchan, China’s youngest medal winner at Tokyo 2020, gained attention for taking up diving to pay for her mother’s medical bills. She later earned a deal with Chinese athletic brand Xtep reportedly worth over $1.5 million. And because of her Olympic victory, her heartfelt story garnered donations from netizens.

But there is a dark side to the shining rewards of ingratiating netizens. When online users express displeasure with the performance, backgrounds, or political comments of Chinese athletes, their dreams can be thwarted in an instant. As a precautionary measure, Chinese athletes have elected to quietly acquiesce to netizen sentiment when it comes to Olympic performance issues. When table tennis duo Liu Shiwen and Xu Xin lost to rival Japan in the final round at Tokyo 2020, the pair issued a tearful apology for having “failed the team,” fearing personal consequences.

In a system where unsuccessful athletes are discarded and where athletes lean on sponsorship revenues to help support their families, the implications for diverging from the political directives of Beijing are also far-reaching. Yang Qian was lambasted by nationalistic Weibo users for posting photos of Nike gear, a brand that has pledged to cease using Xinjiang cotton due to Uyghur forced labor. Domestic athlete sponsors like Xtep and Xiaomi, who have both benefited from Xinjiang forced labor and even gone as far to support it, are likely especially sensitive toward any public comment on the issue.

“In terms of individual athletes, their path between where they are and even greater wealth will run through echoing the rhetoric of the party on issues like Xinjiang,” Sobolik added. “It will be a test of national pride and of patriotism to echo what the party’s talking points are, and the economic incentives are strong to do that.”

These performance and political pressures apply even to China’s naturalized athletes. At Beijing 2022, netizens castigated American-born Chinese Olympian Zhu Yi for her last place finish in the team figure skating event, with some netizens labeling Zhu a national “disgrace” and an “amateur.”

On the other end of the spectrum, American-born Chinese Olympian Eileen Gu has avoided media appearances in recent months, ducking controversial topics such as human rights abuses – potentially because millions in sponsorship dollars were on the line. When she was pressed, Gu echoed Chinese Communist Party (CCP) talking points on the safety of Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai, who accused a senior party official of sexual assault this past November. Yet these politically correct comments, combined with her Beijing 2022 gold medal and popular persona, have won Gu widespread praise from Chinese netizens.

Athletes are also subject to surveillance and image management by the CCP itself. When Reuters covered Chinese weightlifter Hou Zhihui’s gold medal victory with “ugly photos” at Tokyo 2020, government officials tweeted their resentment. Meanwhile, gold medal cyclists Bao Shanju and Zhong Tianshi donned Mao Zedong pins during their medal ceremony last summer – a direct violation of the Olympic Charter, which bans political propaganda – and were met with a mere warning from the IOC while Chinese officials failed to condemn the political display.

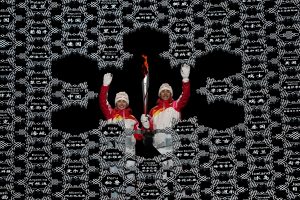

For a nation that has opposed the “politicization of sport” ahead of Beijing 2022, China has used the Winter Games to boost its own national agenda, not excluding its most brash elements. The Global Times used Beijing 2022 as a platform to attract attention to winter sport tourism in Xinjiang and to claim that skiing originated in the region. Earlier this month, People’s Liberation Army commander Qi Fabao, who was injured in the 2020 Galwan Valley border clashes with India, carried the Olympic torch.

Xi Jinping has similarly leveraged Beijing 2022 to receive his first foreign leaders for the first time in nearly two years, including Russian President Vladimir Putin during the Ukraine crisis.

But arguably most controversial among Beijing’s political activities during the Games is Uyghur Olympian Dinigeer Yilamujiang lighting the cauldron at the Olympic opening ceremony amidst international concern over human rights violations in Xinjiang, where experts estimate around 1 million Uyghurs have been forced into involuntary detention. Chinese officials state that its Xinjiang policies are “about countering violent terrorism and separatism” and deny any human rights violations.

“The most obvious politicization, of course, was having a Uyghur athlete light the torch,” said Bonnie Glick, director of the Center for Tech Diplomacy at Purdue University. “It’s a purely cynical move and should have fooled no one.”

This is not the first time Beijing has dispatched Uyghurs to represent China at the Olympics. At Beijing 2008, then-student Kamaltürk Yalqun carried the Olympic flame as a part of its ceremonial journey. While Yalqun said he was proud to represent China at the time, he has since fled to the United States while his father was detained and arrested in 2015 for alleged political subversion. Another Uyghur torchbearer, Adil Abdurehim, is reportedly serving a 14-year jail sentence for watching counter-revolutionary videos.

For Yilamujiang, the consequences of diverging from the party line would be far more serious than lost sponsorship dollars. If she were to speak out of turn with the CCP stance on her home region, Yilamujiang could face a punishment similar to Yalqun’s father or Abdurehim. Her silence, then, is “another instance of the party controlling the individual athlete, and at a meta-level, controlling the expression of individual people inside the country,” said Sobolik of Yilamujiang’s situation.

After finishing 43rd in the Women’s 15km skiathlon event, Yilamujiang dodged media interviews and vanished from the public spotlight until her next race on February 10. She was subsequently dropped by Team China from her final event.

Similarly, for the first time, Tibetan athletes are representing China on the Olympic stage, but we shouldn’t expect them to speak up about Tibetan issues. These athletes will have no choice but to avoid sensitive questions, even those regarding human rights violations occurring in their own home region.

While some American athletes have voiced “conflicted feelings” on competing in the Games, Chinese athletes remain silent at the risk of facing online unpopularity (including coordinated attack campaigns on social media), sponsorship loss, or at worst, severe political consequences. With intensified personal surveillance in the Olympic bubble, fierce netizen fervor, and the Chinese government’s narrative sensitivity all coalescing around Beijing 2022, the Winter Games themselves will not be the only difficult challenge Chinese athletes face. They will also have to navigate the mental pressure of walking a thin line between athletic success and political correctness.