We touched down in Managua, Nicaragua, shortly before 7:50 p.m. on July 18, 2014. The tickets were originally booked for a cheaper flight the following day, but Pablo Morales was having none of it.

“It’s Liberation Day,” he said. “You have to be here. It will be special.”

He greeted me with a clasp befitting his ursine physique and insisted on carrying my luggage – a solitary battered backpack – to the car. Whispering in from the Pacific, the evening breeze had taken the heat down a notch from oppressive to somewhere just above sultry.

The previous afternoon, on a tour of Panama City’s old Chinatown with a local historian, I had mentioned my plans to attend the celebrations in Managua. My guide raised a startled eyebrow. “Be careful with those Sandinistas,” he said. “They’ll try to convert you for sure.”

Perhaps Morales discerned a ripple of that warning in my furrowed brow as he navigated the downtown traffic enroute to his home in the suburbs. “First thing to know,” he said. “I’m a Sandinista, but I won’t try to make you one.”

Pablo Morales (a pseudonym) was as good as his word, but his word wasn’t the problem.

Propaganda is everywhere in Nicaragua; the cult of President Daniel Ortega and his Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) is pervasive. Spray-painted images of El Comandante, fist clenched as he hollers a clarion call to the masses; constant updates from the president’s office running as banners at the bottom of the screen during daytime lifestyle programs on state TV channels; the utopian spin on almost every action or event in which the government plays a hand; and Stalinesque accusations of sabotage carried out by nebulous malefactors when things are not quite up to scratch.

The Liberation Day 2014 celebrations were a perfect example. I’d been led to believe that it was Nicaragua’s independence day, which it’s not, and that it was an event joyously celebrated by all Nicaraguans, which it isn’t. The distinctly underwhelming attendance at Plaza de la Revolución, formerly Plaza de la República – further demonstrating how the FSLN has bound the country’s identity to the party – was explained away by the revelation that a bus from the Sandinista Youth wing had been attacked by “right-wing terrorists.”

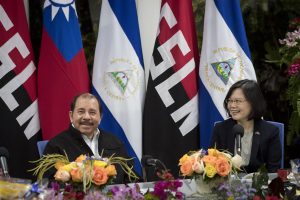

Several Sandinistas insisted this was a regular occurrence, and indeed, there were two more reports of attacks against party supporters in the next few days. One of these I caught over breakfast in the Morales family home. Coincidentally – considering I had come to Nicaragua to probe the country’s relations with Taiwan – the banner announcing the news ran along the bottom of the screen during a segment about a Taiwanese woman who ran a KTV in Managua.

Elsewhere, other Nicaraguans poured scorn on the claims. “Any time things don’t turn out the way they want, it’s a right-wing plot,” said a contact with ties to opposition groups.

Yet if Ortega and his followers saw enemies everywhere, it was not completely without reason. The causes of this paranoia lie at the heart of my decision to make that trip in 2014. I was not investigating the present-day claims of conspiracy, but skulduggery that dated back decades. Eventually, I found that the two coincided in the unlikeliest of manners.