The metaverse has been described as many things: the next evolution of social connection, dangerous by design, the future of the internet and an unprecedented business opportunity. Its definition will undoubtedly continue to shift. But whether future or fad, one thing is certain: China will not miss out on shaping this new ecosystem. A metaverse with Chinese characteristics is being built – and it may end up becoming a $8 trillion market.

Chinese players are venturing into new virtual worlds with a speed to match Silicon Valley’s. There have already been 16,000 metaverse-related trademark applications filed and tech giants have been investing into the software, hardware, and key infrastructure needed for a metaverse to exist. Tencent, for example, announced a joint venture with Roblox in 2019 and has since assembled a strong metaverse-related portfolio, covering everything from social media and gaming to cloud computing. Alibaba has made investments in augmented and virtual reality companies since 2016, while Baidu launched the virtual world XiRang, and ByteDance has strengthened its metaverse hardware capabilities by acquiring the VR headset maker Pico. These are just a few of the many examples of Chinese firms exploring the possibilities of the metaverse.

Beijing, however, has remained ambiguous toward the concept. Despite hints of caution and state-affiliated think tanks flagging national security risks, China’s leaders also see the metaverse as an innovative technology to support. As is often the case in China, the most interesting experimentation is happening at a local government level. In late 2021, not long after Facebook renamed itself to “Meta,” the Shanghai government announced that the metaverse would be a part of its 14th five-year plan for developing the electronic information industry, calling it one of four frontiers for exploration. Other local governments, such as Hebei province and Wuhan city, quickly followed suit. Various municipal governments have organized metaverse development seminars and discussions.

Ultimately, whatever the risks, experts agree that the benefits of supporting a Chinese metaverse outweigh these. Developing critical infrastructure for the metaverse, such as development clusters or supercomputing centers, will have positive spill-over effects on other local technology industries, boost economic development, and attract talent – all while ensuring that China builds a metaverse on its own terms, instead of letting others dominate.

If things are moving so quickly, it is because the metaverse has struck a chord with young Chinese consumers. But this is not entirely new – even before official metaverse apps appeared, all the ingredients for it existed. With most daily activities being supported by technology, the concepts of digital worlds, connections, and value are widely accepted.

Various avatars on QQ Show.

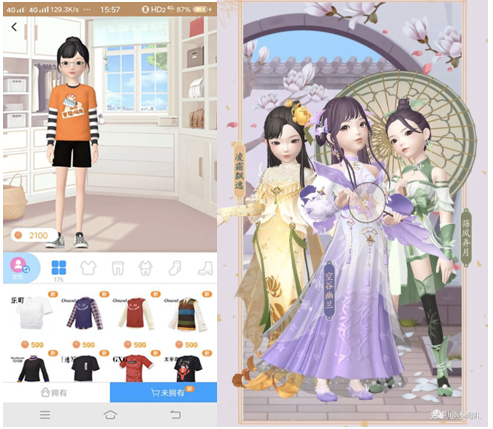

Apps such as QQ Show, a virtual avatar builder linked to Tencent’s QQ messenger, were highly successful in the early 2000s. Many millennials enthusiastically dressed their avatars, but rejected this platform and its overt styles when new social networks with minimalist design and “real profiles” became the mainstream in 2010s. Cut to the present, 3D avatar builders like Zepeto and Taobao Life have adapted to this and given consumers the opportunity to creatively express themselves, becoming part of a larger social group that fits their interests and habits. Hence, for many Chinese consumers, virtual life and identity in the metaverse are just a natural evolution to connect with peers.

Taobao Life, which features niche subculture fashion like Hanfu.

One interesting case study today is the metaverse social app Zheli, which recently overtook the dominant social networking app WeChat as the most downloaded app in the Chinese App Store. An intimate social experience that only allows for 50 friends per user, this exclusivity paired with its fashionable character designs captured the hearts of young users. And this should hardly come as a surprise. Over the years, as WeChat became the all-in-one platform for socializing, business networking, and keeping in touch with family, young users began wishing for a separate space where they could express themselves more freely – the metaverse has offered exactly this.

Soul, another widely popular metaverse social networking app, is also a poignant example. It uses an algorithm to connect its users through common passions and hobbies. Through features such as AR enabled video chats or voice call matching functions, Soul carefully balances the freedom of virtual identity with the excitement of real connections. Qiushu, a user on Zhihu (China’s Quora), views Soul as the place where he can indulge in his quirks and passions unashamedly. He comments, “Most people have fixed social circles in real life. In those circles, we tend to hide ourselves to fit in with societal norms.” For him, no matter how random his status updates read, reactions from the community of virtual strangers-turned-friends have been nothing short of wholesome.

Soul has embraced the fact that China’s new generation is open, curious, and creative. Subcultures abound, varying from gufeng (traditional Chinese aesthetics) to Japanese New Wave cinema. Chinese youths are eager for deeper connections through niche, creative topics in boundless virtual worlds.

Soul’s AR video call function. Courtesy of Soul official website.

A Metaverse With Chinese Characteristics

One key aspect that differentiates this Chinese metaverse is government control and political censorship within a yet-to-be-defined regulatory strategy – making Chinese companies cautious after a year of regulatory constraints targeting ed tech, children’s gaming time, personal data protection, cryptocurrencies, and tech monopolies in the government’s shift to “common prosperity.” NFTs, for example, cannot be traded (only collected) and cryptocurrencies cannot be used. In December last year, Roblox had to pause its operations in China, with some speculating that it might have taken the company more time to secure regulatory greenlight.

But there are other factors that differentiate the Chinese metaverse. For example, while most explorations within the metaverse are focused on visuals, there is an opportunity to develop socializing through voice in China. From social singing app WeSing, to podcast and audiobook giant Himalaya FM, livestream and user-generated audio content that provides companionship and community building is what keeps users coming back. While many Western apps focus on best-in-class functionality, Chinese apps tap into consumers’ desire for human connection. Even as people are interacting through avatars or screens, putting a human voice to an object immediately makes it more human or genuine. A voice gives us hints to a person’s personality, and sparks our imagination, creating deeper connections. In a country obsessed with live streaming and companionship, a voice enabled metaverse would strike the fine balance between being anonymous, creative, and genuine.

Furthermore, what we have already observed with Douyin (TikTok) and Kuaishou is that different worlds emerged from urban and rural creators. For example, while urban creators on Douyin are showing off the latest exhibition or trending dance moves, rural or small town creators on Kuaishou go viral for their absurd and crass style (also known as Tuwei) performances. We may start observing a similar development on metaverse apps, as separate worlds, styles, and sub-genres emerge across a rural-urban divide. It remains an open question, whether this new space becomes a level playing field, or whether the aspirations, tastes, and monetization opportunities of urban vs. rural Chinese users will differ and lead each to different platforms.

Implications for Brands

Bringing all of these elements together has an impact on brands. For example, so far luxury brands have been reluctant to enter China’s metaverse due to limited opportunities for monetization within current regulations. According to research by Jing Collabs & Drops, in China, unlike in the West, there is no resale market for crypto assets and digital collectibles value is limited, meaning that many brands see the metaverse as a marketing opportunity via art toys, games, or idols rather than a direct source of profit. These marketing strategies will in turn need to be aligned with the local preferences of young consumers and their desire for exciting experiences and connection.

With a thriving Key Opinion Leader (KOL) market, one especially interesting trend is working with virtual influencers or idols – an industry that is expected to grow to 333.47 billion RMB ($52.4 billion) by 2023 according to iiMedia. The human look-alike AI idol Ayayi has already promoted major brands such as Guerlain and TMall events, working both online and offline.

But luxury and fashion brands are not the only ones who could benefit from adapting to the Chinese metaverse. Given the success of relaxing life simulation games like Animal Crossing, we can expect demand for more mundane activities to get a metaverse uplift. This means that fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) brands can play a more active role in consumers’ lives. For example, educational metaverse cooking games could be one way to introduce a soy sauce brand to young consumers while providing them with useful knowledge, while the online shopping experience for physical goods could be transformed by taking place in a metaverse (which Alibaba is developing).

Increasingly, online and offline worlds will be merged. Imagine a young couple enjoying a grocery run in their metaverse homes, where they can shop based on their preferred experience, whether it is a meditative stroll through biophilic design supermarket aisles, or a cyberpunk themed store to shop for themed limited-edition digital collectible products. But the key point is that consumers are not interested in just a metaverse version of a product ad. Instead, they have flocked to the metaverse for human connection and brands need to create real value that enhances consumers’ lives – focusing on the many subcultures, trends, rural-urban differences, and unique experiences.

In conclusion, the metaverse is growing rapidly in China and young Chinese consumers have embraced these new worlds as a natural evolution, giving them new freedoms and ways to express themselves by building intimate social connections. There are many opportunities for brands to become a part of this ecosystem. However, this will be different than in the West: To succeed in China’s metaverse, brands cannot copy-paste approaches and will need to be nimble, adapting to local rules and local preferences. Reduced direct monetization, different subcultures, rural-urban divides, and features such as virtual idols or voice are just a few to be kept in mind.