Does the South Korean public support a peace treaty with North Korea? My original survey work shows that, despite recent missile tests by North Korea and the lack of meaningful inter-Korean dialogue, a clear majority of South Koreans approve of the idea. Even among those who had planned to vote for Yoon Suk-yeol, the conservative presidential candidate (and now president-elect) a thin majority support a peace treaty, in contrast to Yoon’s rhetoric about a tougher stance toward North Korea and the expectation that his administration will not continue President Moon Jae-in’s call for a peace treaty without first denuclearization efforts by Pyongyang. However, the public may view a treaty as aspirational, not considering the logistics or feasibility now, allowing Yoon to end such overtures.

Yoon’s election victory is expected to lead to a hawkish pivot in South Korea’s policy with North Korea and away from the engagement efforts under Moon. At the first inter-Korean summit between Moon and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, both sides declared support for efforts to lead to a peace treaty that would formally end the Korean War. However, there has been little progress beyond this abstract agreement, and no summits since 2019. Moon, however, remained optimistic about the resumption of talks and continued to push for a peace treaty. Thanks to Moon’s insistence, the U.S. and South Korea agreed in principle on an end of war declaration, despite little participation by North Korea leading up to the announcement.

For its part, North Korea routinely demands the end of the United States’ “hostile policy” as a necessary precondition for a treaty, while the U.S. has resisted taking such a step without concrete evidence of denuclearization. Moreover, North Korea tested nine missiles this year prior to the South Korean presidential election. Such bellicose actions would be expected to sour South Korean public interest in a peace treaty.

A peace treaty would have symbolic importance, maintaining hope for, if not reunification, at least peaceful coexistence, especially at a time where more South Koreans would choose the latter over the former. However, the practical benefits of a treaty are unclear, especially as North Korea continues its missile program. Similarly, the logistics of all parties signing a peace treaty, which presumably would also include the United States and China, seem unlikely.

As a candidate, Yoon seemed disinterested in these end-of-war efforts, stating that a treaty would only be “will be done only on paper with ink” as long as North Korea has nuclear capabilities. This perhaps gets to the heart of the issue, where South Koreans may in general be supportive of a peace treaty, but differ on whether there should be no explicit preconditions or whether concessions from North Korea, such as verifiable denuclearization, must come first.

To address public perceptions, I conducted a web survey before the South Korean presidential election, via Macromill Embrain on February 18-22. In this survey, I asked 945 South Koreans “Do you support a peace treaty between South Korea and North Korea?”

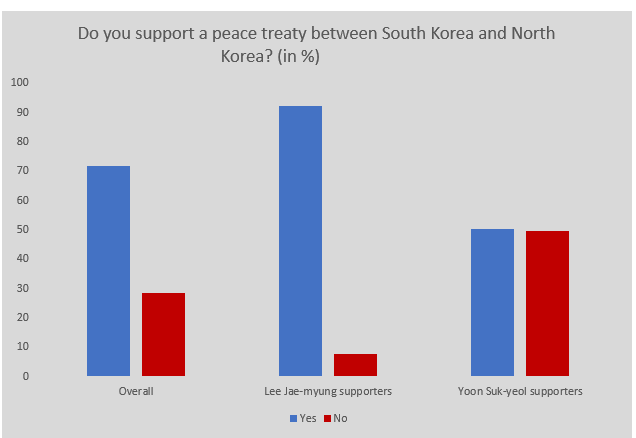

Overall, a clear majority support such actions (71.64 percent). However, among supporters of the two main candidates we see clear distinctions, with the vast majority of Lee Jae-myung supporters in favor (92.24 percent) compared to a slim majority of Yoon’s supporters (50.37 percent). Several factors could explain these patterns. Support among those who were planning to vote for Lee would be consistent with liberal-progressive support for “Sunshine Policy”-type programs that aim to warm inter-Korean relations. In contrast, Yoon’s supporters, consistent with conservative parties more generally, may be apprehensive of negotiations with the authoritarian state, which candidate Yoon referred to as a “archetype of a failed state,” especially negotiations that potentially reward North Korea without requiring a change in behavior. Still, considering the lack of progress toward warmer relations across the peninsula, that majorities support a peace treaty is surprising.

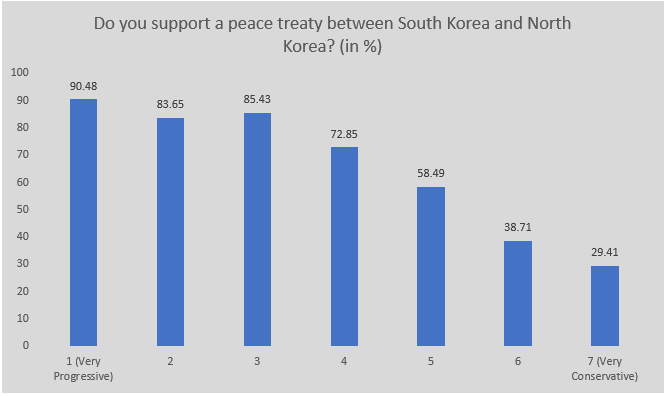

Breaking down support by political ideology provides additional insight. Admittedly, ideology corresponds strongly with vote intention, with over 60 percent of those identifying as left of center (1-3 on a seven-point ideology measure) supporting Lee and those right of center (5-7) supporting Yoon. However, when broken down by political ideology rather than vote choice, we see a clear decline in support as one moves across a seven-point progressive-conservative scale. Among the very progressive, 90.48 percent of respondents support a treaty, dropping to only 29.41 percent amongst the very conservative.

Regression analysis gives further insight. Controlling for demographic factors as well as ideology and candidate support, only age and support for Lee positively correspond with supporting a peace treaty, while ideology and support for Yoon negatively correspond with support. Switching out the candidates for their respective parties produces similar results. In addition, those who evaluated Moon’s presidency more favorably, controlling for partisan and demographic factors, were also more likely to support a peace treaty.

What does this mean for President-elect Yoon? Admittedly, the limitations of this survey work do not allow us to identify the weight the South Korean public gives to a peace treaty compared to other factors such as housing or jobs. Nor can it capture whether the public has fully considered the complexities involved in such arrangement. In other words, the findings may be a more visceral response to the idea of a peace treaty and not factor in what would be necessary for it to have more than symbolic meaning. Yoon must also contend with a North Korea that has decided to scrap its moratorium on intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) testing and may be preparing for a nuclear test, incentivizing a more hardline stance while limiting support for even rhetoric about engagement.

Thus, while a public may seem supportive of a peace treaty, recent actions by North Korea as well as domestic concerns in South Korea will likely lead Yoon to spend little effort promoting such efforts.