Chen Yuying remembers the freezing afternoon last December, when she was sitting in the back of the classroom watching other students writing. Shielded by her glasses and facemask, she quietly burst into tears.

For the past two days, she had tried her best to stay calm and fully focused on the exam. But after finishing answering all the questions, she was overwhelmed by mixed emotions and thoughts.

She figured she did a fairly good job in the test and was confident about achieving her only goal for the past year – to “land” or to be accepted by a master’s program. Yet some of her friends might not be as lucky, and she was afraid their pathways could thus get further and further away.

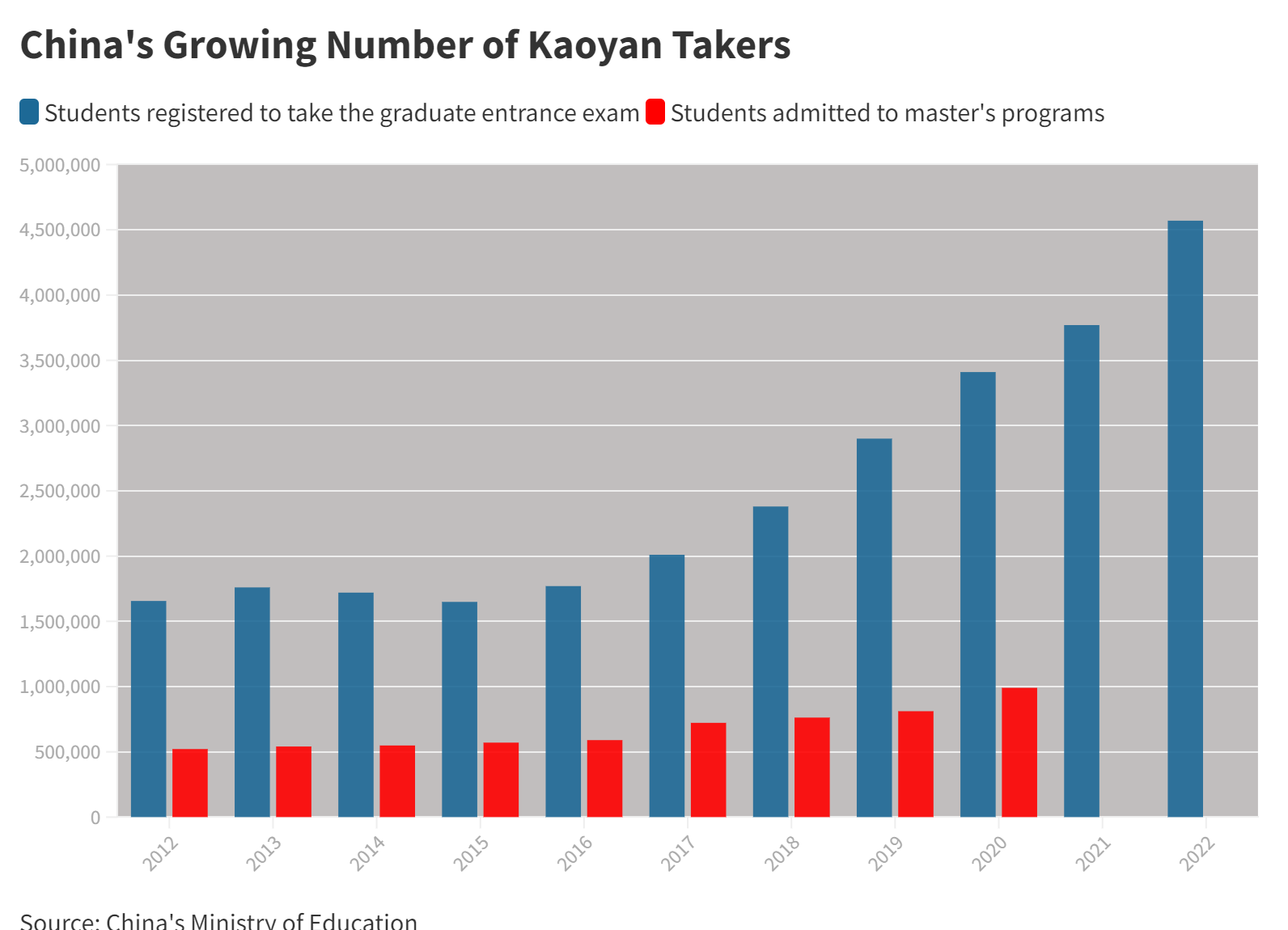

Chen, a 23-year-old studying aquaculture at Jilin Agricultural University, was one of the millions participating in China’s yearly national graduate entrance examination, or kaoyan, which mainly targets bachelor’s degree holders who want to continue their studies for a master’s. Last December, a record 4.57 million people registered to take the exam, 21 percent higher than the year before, and double the number compared to five years earlier.

Wu Xiaogang, a professor of sociology at New York University Shanghai, argued in a recent column published on Sixth Tone that China is facing degree inflation. More and more Chinese are turning to graduate studies to boost their chances in the job market, but the size of graduate programs has not expanded at the same rate.

In China, a country with a rich examination culture, the college entrance exam or gaokao, has long been seen as the first and most important turning point of one’s life. The score students achieve on the gaokao largely determines the level of university they are able to attend, which can, in a competitive job market, make or break careers.

But as Dai Kun – an assistant professor in educational administration and policy at the Chinese University of Hong Kong – observed, information and resources that are unequally distributed among different social groups have become increasingly essential for good performance, making it increasingly difficult for students of low economic backgrounds to compete in the gaokao and break into the very top universities.

Therefore, kaoyan, recently nicknamed “the little gaokao,” has become a second chance for students – especially those from second-tier universities – to transform their lives, according to Dai. Students who succeed in the exam can study at the universities they’ve chosen – normally more prestigious ones.

As of September 2021, there are over 1,000 universities in China, according to the Ministry of Education. They can roughly be divided into four layers, with Tsinghua University and Peking University at the top. Next up are the other so-called “211” and “985” universities listed in key national projects for promoting higher education. Ordinary first-tier universities are below them, with second-tier universities at the bottom. The distribution of academic resources, education quality, and even the fates of the students, are all largely related to which layer their university sits in.

For undergraduates from top universities, taking the graduate entrance exam is not a priority. Zhang, a former undergraduate student at Peking University who asked to be identified only by her surname for privacy reasons, remembers it was rare for students of her department to take the exam or walk directly into the job market. Instead, a lot of them chose to study abroad, and about one-third of the students were entitled to apply for a master’s in China through the postgraduate recommendation system, according to her.

Designed by the Ministry of Education, the postgraduate recommendation system aims to select “outstanding undergraduates” across the country to continue studying their master’s without taking a writing test. Compared to sitting for the kaoyan, it’s considered less risky to access a master’s program through a recommendation.

But universities can only make recommendations of their top ranked undergraduates when they are authorized to do so. As of 2018, there were only 367 authorized schools, according to the official website for information regarding master’s applications in Chinese universities – meaning over 60 percent of universities cannot offer recommendations for their students.

Among the authorized schools, recommendation quotas also vary. Wu Xiaohan*, who studied her bachelor’s degree at a “211” university in Beijing, said about one-fourth of the students in her class, including her, were given the chance to be recommended. The recommendation rates of Tsinghua University and Peking University can even top 50 percent, according to data from the China University Rankings website.

But getting recommended has never been an option for Mona Meng, who studied her bachelor’s at a second-tier university in Hubei province – one that’s not authorized to make recommendations. (She was only willing to give her English name due to privacy concerns.)

Meanwhile, graduating from a second-tier university also means less advantages in the job market. An HR person from a leading Chinese tech company – who asked for anonymity as they are not authorized to speak representing the firm – said that for most jobs, her company doesn’t have a hard restriction on their applicants’ university level. But for full-time positions opening to fresh graduates, second-tier university applicants won’t pass the resume selection stage unless they have had a couple of really impressive internships, she said.

Acknowledging the disadvantages a second-tier university undergraduate will face, Meng decided she had to participate in kaoyan from the first day she went to college. In her class, almost 70 percent of the students made the same decision, according to her. With full support from her family, Meng attended the exam three times, and has now been accepted onto a master’s program at a “985” university in Tianjin.

But not everyone has Meng’s determination or family support to repeatedly take the exam. Xu Wenlong, who studies at a second-tier university in Northeast China, said he won’t try for a second time after failing the exam last December. For him, the best time to prepare for the exam is when he’s still at school. Now he’s graduating soon, and it’ll be difficult to stay focused afterwards, he thinks.

Xue Meiling*, a 25-year-old from China’s Sichuan province, won’t take the exam again either. In the past year, after quitting her job in Indonesia when the pandemic hit, she rented an apartment in Chengdu and faked an entrance card to her previous university for access to its library, to prepare for the kaoyan.

Hoping to gain the knowledge and skills to make an impact in public policy, Xue chose to apply to the public management program at Tsinghua University. Last December, she scored 393 in the writing test, way above the 355 score required for the admission interview – which, unfortunately, she failed.

“I used to feel that I should devote myself to serving the people. But once I failed, I don’t feel I have the capital to do it again anymore,” she said. “I feel like the country closed its door for people who want to do something or devote themselves to enter into the system.”

“Or perhaps they don’t lack a ‘talent’ like me after all.”

Xue’s family members don’t know this story. Instead, she has told them she is working for a state-owned company. Xue thinks that telling her family will only create drama, instead of earning their support.

Judging from the estimate that less than a quarter of those registered to take the exam will finally make it onto a master’s program, as Wu of NYU Shanghai wrote in his column for Sixth Tone, failing the exam is an experience shared by the majority of participants.

The severe competition comes as China goes through an economic downturn as it faces challenges from the ongoing pandemic and its crackdowns on tech, tutoring, and real estate industries – sectors that used to be favored by university degree holders but have recently suffered large scale layoffs. Last month, the country’s official urban jobless rate climbed to 5.8 percent, the highest since May 2020. There are also more than 10 million graduates, a record number, entering the job market this year.

Wu argued that the trend toward degree inflation – and fierce competition – is here to stay. “By the time today’s postgrads complete their studies, having a postgraduate degree will be even less of a guarantee of good employment than it was when they enrolled,” he writes.

Wu described the reality that Yang Yang, who will soon graduate from a Shanghai “211” university with a master’s degree, is facing. Despite having studied journalism for seven years and internships with several leading Chinese media outlets, she’s still struggling to find an ideal job.

Graduating in the same year, Han Han* has secured a job in a fund management firm, though he had to make compromises. Originally, he wanted to work for an investment bank. Studying a master’s in finance at Tsinghua University, Han didn’t think there would be an issue landing his dream job. But his resume didn’t survive the selection process of any investment banks. The reason for that, Han speculates, is because his bachelor’s degree is from a non- “211” or “985” university.

He was frustrated for a while. “I’ve put so much effort into preparing for the postgraduate exam for two years, but then I figured the world is different from how I imagined it to be,” he said.

As a second chance for some students to make a life change, the kaoyan is still there – but in the actual labor market, it’s not only the second degree that’ll be assessed by “wonderful” employers, Dai with CUHK argued. Discrimination against an applicant’s first degree is a common practice, he said.

He feels that society is ignoring people’s efforts to chase their dreams. The better universities you attend, the better opportunities you will have; but if you lose one step, you’ll risk losing the rest of your life,” he said.

“Society should give more inclusive thinking for people who cannot get continuous ‘success,’” he argued.

*These interviewees requested pseudonyms, citing privacy concerns.