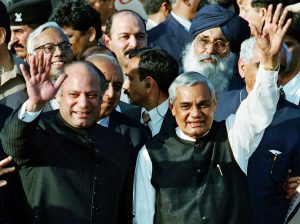

Twenty-four years ago this month, India and Pakistan declared their nuclear weapons capability to the world. Remarkably, in 1999, less than a year after their tests, both states signed the Lahore Memorandum of Understanding to enhance mutual trust in a conflict-prone environment and assuage international fears.

Although the conflict in Kargil limited the immediate influence of the document, its forward-looking character was recognized then, and is stressed even today. This was evident in the prolific references to the MoU by commentators after an unarmed Indian missile misfired, landing in Pakistan. However, a review of the MoU today reveals that despite enduring relevance, it remains partially fulfilled on a few core aspects.

The Agreements That Were

Where the Lahore MoU has unambiguously succeeded is the joint undertaking for India and Pakistan to notify each other of ballistic missile flight tests. The 2005 agreement in this regard is a direct result of clause two of the MoU, which was a primer for more expansive confidence-building measures (CBMs). Calls by numerous experts to now extend the ambit of the agreement to cruise missiles is testimony to the potential for step-by-step progress on such CBMs.

Similarly, the 2007 Indo-Pak agreement on nuclear weapons related accidents can be directly traced to clause three of the Lahore MoU. This agreement, scheduled for its third renewal this year, extends the MoU’s commitment to the adoption of “measures aimed at diminishing the possibility of… such incidents being misinterpreted by the other,” and establishing “appropriate communication mechanisms for this purpose.”

However, this has not been aided by any mutually affirmed implementation procedures. For instance, Article 4 provides for hotlines at the Foreign Secretary or DGMO levels, or “any other appropriate communication link for…transmission of urgent information.” There is no clarity on either the communication mechanism or the nature of information to be shared. While ambiguity in general can be a characteristic of deterrence, in the case of CBMs this lack of clarity prevents the effective fulfilment of the objectives both sides seek to achieve through them.

Expert scholarship has detailed a range of cooperative measures needed to promote the 2007 agreement, focusing on potential areas of vulnerability, communication links, and transparency measures on nuclear safety. Given the stagnant state of political relations, deliberations on these measures should be pushed through a focused military-to-military dialogue, modelled on the intelligence-led backchannel between the two states. While insulating any communication track from the political dispute is difficult, the militaries of both states have already displayed the capability and intention to uphold operational CBMs.

The Doctrinal Impasse

The very first clause of the MoU calls for “bilateral consultations on security concepts, and nuclear doctrines.” This is reiterated in clause eight, with non-proliferation as its context. However, it is in the doctrinal space where the dilemma is greatest. The contrast exists at two levels: nuclear force posture and risk manipulation.

While India seeks to use its nuclear arsenal to deliver an incapacitating second strike or “massively retaliate” in response to a first strike on its territory or troops, Pakistan’s unstated doctrine attributes a dual role to its arsenal – to deter India from initiating a conventional war, and to deny India victory in case war breaks out. Hence, a first strike character is inbuilt in Pakistan’s thinking. The prevailing belief in India is that Pakistan seeks to incorporate nuclear weapons for war-fighting, evidenced by its development of battlefield nuclear weapons, although some Pakistani experts have pushed back by insisting that Pakistan’s “Full Spectrum Deterrence” (FSD) is equally about conventional modernization and operational readiness, rather than just nuclear forces.

While risk management is a crucial part of nuclear confidence building, the India-Pakistan situation is complex. While India has indicated its red lines through a declared doctrine (and adheres to it, despite some deviant perceptions in recent years), Pakistan’s nuclear deterrence is centered on risk manipulation. Feroz Khan, formerly of Pakistan’s Strategic Plans Division, has outlined that this involves creating uncertainty in Indian military planning by denying it room for conventional operations (as redlines are not defined); failing this, the presence of tactical nuclear weapons creates enough uncertainty to prevent further prosecution of the war.

While Pakistan overtly declaring a doctrine would likely undermine its “managed instability” concept, conversations with India on specific aspects that form a nuclear doctrine would further the Lahore MoU’s objectives. It would allow both countries to discuss the trees, while avoiding the woods.

Speaking with the author at an event marking the test’s anniversary, Manpreet Sethi stressed the necessity of this conversation to gain clarity on specific aspects. Pointing to the Pakistani assertion that their tactical nuclear weapons are subject to centralized command and control, she stated that this counters the very concept of a “tactical” weapon, which necessarily requires delegated control. Without clarity on such aspects, other states cannot figure what terms like FSD mean.

She cautioned however, that without the political relationship improving, such dialogue is not forthcoming.

This doctrinal disparity also spills over onto other CBMs. In subsequent correspondence, Sethi highlighted that a possible hindrance to extending the 2005 agreement is the different character of cruise missiles on either side. For Pakistan, the missiles are meant for nuclear payloads, while India primarily assigns conventional warheads to them. Notably, despite national coverage of the BrahMos missile constantly referring to its “nuclear capability,” the official categorization of the missile highlights only its conventional capability. Hence, Sethi asserted that any future CBM shall have to cater to this disparity.

The Agreements That Weren’t

The Lahore MoU also commits both sides to abiding by their unilateral moratorium on nuclear testing. Although this understanding has held so far, an agreement formalizing this commitment cannot be envisioned without bringing in China – which is India’s chief nuclear concern. This dynamic is reflected in Pakistan expressly calling for an agreement to cement the moratorium, but India being disinclined to consider it. China has always factored heavily in the nuclear dynamics of the subcontinent, but was not party to the Lahore MoU.

However, Indian experts have asserted that a nuclear taboo continues to exist in South Asia to some degree, arguing against claims that it is under more stress in the region particularly. Hence, the “no more testing” policy, albeit undeclared, is perhaps aided by the desire by either state not to proliferate vertically.

The Lahore MoU also called for an agreement for the prevention of incidents at sea to ensure safe navigation by naval vessels and aircraft. In its wake, a report from the U.S.-based Stimson Center had delineated measures that could supplement this through maritime CBMs such as the establishment of Maritime Risk Reduction Centers (MRRCs) for exchanging information on issues including maritime boundary violations and firing tests. Moreover, it was suggested that such MRRCs be made part of Nuclear Risk Reduction Centers with a broader scope.

However, unlike clauses two and three, the maritime clause of the MoU never led to a formal agreement. Ideas such as the NRRC, which has received support from strategic experts on both sides, remain in the air. As recently as this February, Pakistan arrested 31 Indian fishermen, alleging their intrusion into its exclusive economic zone.

A maritime agreement drawn from the MoU would help the naval forces of both states to deal with local day-to-day disputes better. The logic is similar to the few but important Standard Operating Procedures that exist at the Line of Control (which also await formalization). The agreement would not only bolster specific measures, such as the 2008 Agreement on Consular Access to aid imprisoned fishermen, but also help develop stakes for the resolution of the broader political dispute between the two states.

Clearly the importance of the 1999 Lahore MoU cannot be overstated. Even two decades since, it holds the potential to serve as a base document for future agreements and removes a lot of the diplomatic weightlifting needed to identify areas where CBMs can be developed. It only needs political will to live up to its full potential. Fortunately and unfortunately, the Lahore MoU even today remains “forward-looking.”