Russia’s invasion has instilled a new raison d’être into democratic formats more generally and the G-7 in particular. G-7 leaders and like-minded partners have delivered a surprisingly united and decisive response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s transgressions. However, Russia is not the only competitor that liberal democracies need to worry about. The broader and more comprehensive challenge facing them will likely come from China.

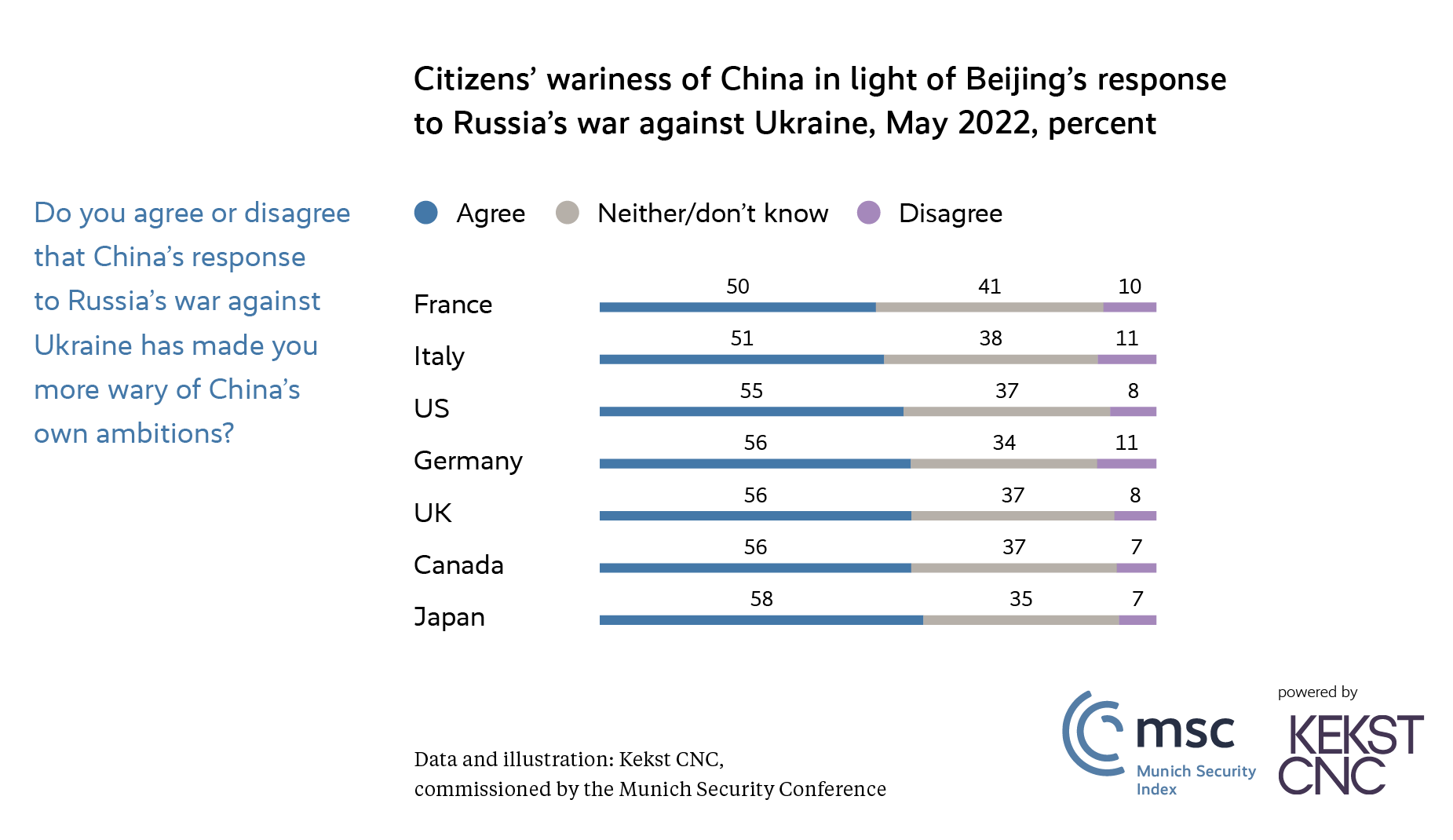

Evidently, in the context of the war against Ukraine, democratic societies have become keenly aware of the threat posed by China. As new public opinion data from all G-7 countries reveals, the crisis in Eastern Europe has not only deeply affected societal views of Russia; it has also triggered a radical reassessment of China. Beijing’s failure to condemn Russia’s unprovoked and unjustified attack against its neighbor, data collected for the Munich Security Conference shows, has not gone unnoticed by respondents in Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the U.K., and the US.. Majorities in all G-7 countries say that Beijing’s response to the war in Ukraine has made them more wary of China’s own ambitions – from 50 percent of respondents in France to 58 percent of respondents in Japan.

With the invasion of Ukraine, abstract concerns about Russian revisionism have become palpable. But the war has not only pitted like-minded democracies against the autocratic regime in Moscow. Among political leaders, it is perceived to have set democracies on a much more confrontational path with autocracies more generally. Beijing’s candid support for Moscow and its apparent willingness to accept the costs that come with it – including growing tensions with the West – is seen as a strong case in point. Apparently, people in the G-7 countries share this assessment. Absolute majorities in Canada, the U.S., Italy, Japan, and Germany believe that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is amplifying competition between the world’s democracies and autocracies. In the U.K. and France, fewer people share this perception, but they outnumber those who disagree by a decisive margin.

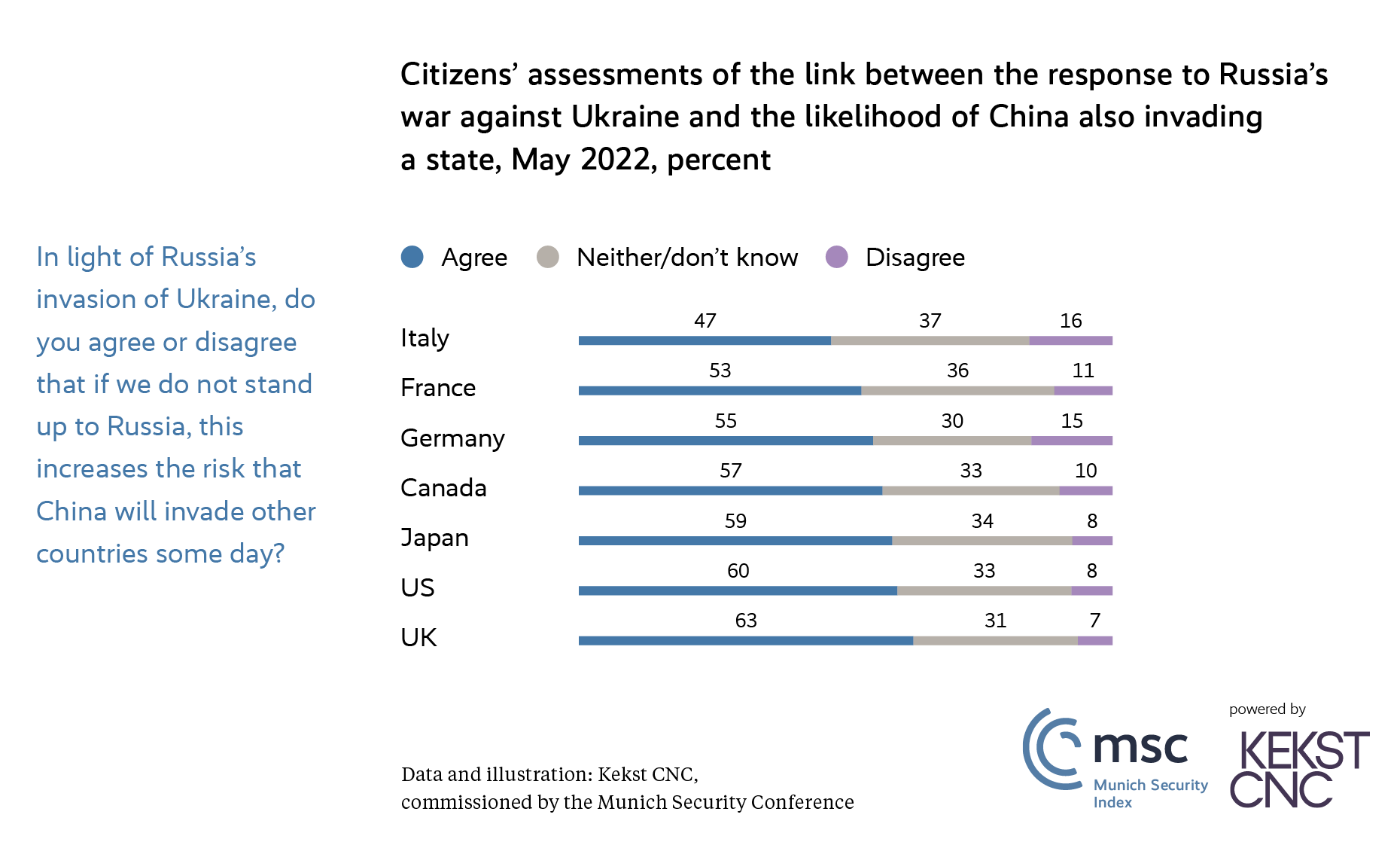

Evidently, views of China have not only hardened; among liberal democracies, the impression is growing that the risks posed by Moscow and Beijing can no longer be compartmentalized. Some politicians have already voiced concern that a failure to stand up to Moscow might embolden China to also engage in aggression. “Ukraine,” Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has warned, “may be East Asia tomorrow.” With the exception of Italy, absolute majorities in all G-7 countries seem to share this perception. They agree that if their countries do not stand up to Russia now, this will increase the risk that China will invade other countries some day.

If like-minded democracies see the threats posed by China and Russia as increasingly being linked, they urgently need to muster the same type of unity and resolve they have shown in the face of Russia’s aggression in their policies toward China as well. And in fact, societies in G-7 countries have become more willing to oppose China economically and militarily than they were before the war – with the divide between continental Europeans and the other G-7 societies shrinking. However, agreement on the right way to deal with China is not as far-reaching as it is in the case of Russia. Among continental Europeans, people are still far less convinced their countries should oppose China economically than their counterparts in the other G-7 states.

When G-7 leaders meet in Schloss Elmau for their summit in a few days, China is not one of the official priorities of the agenda. Yet G-7 leaders urgently need to coordinate their approaches to Beijing. Uniting key democracies from North America, Europe, and Asia, the G-7 is uniquely equipped to discuss not only what recent developments in Ukraine mean for democratic states’ policies toward China, but also what they mean for a joint response to autocratic revisionism more broadly – a response that connects the European and the Indo-Pacific arenas. With G-7 societies having woken up to the threat posed by both Moscow and Beijing, the timing could not be much better.

This article is based on data collected for a special edition of the Munich Security Index, a joint project by the Munich Security Conference and Kekst CNC. The index was published as part of a new Munich Security Brief on June 21, 2022.